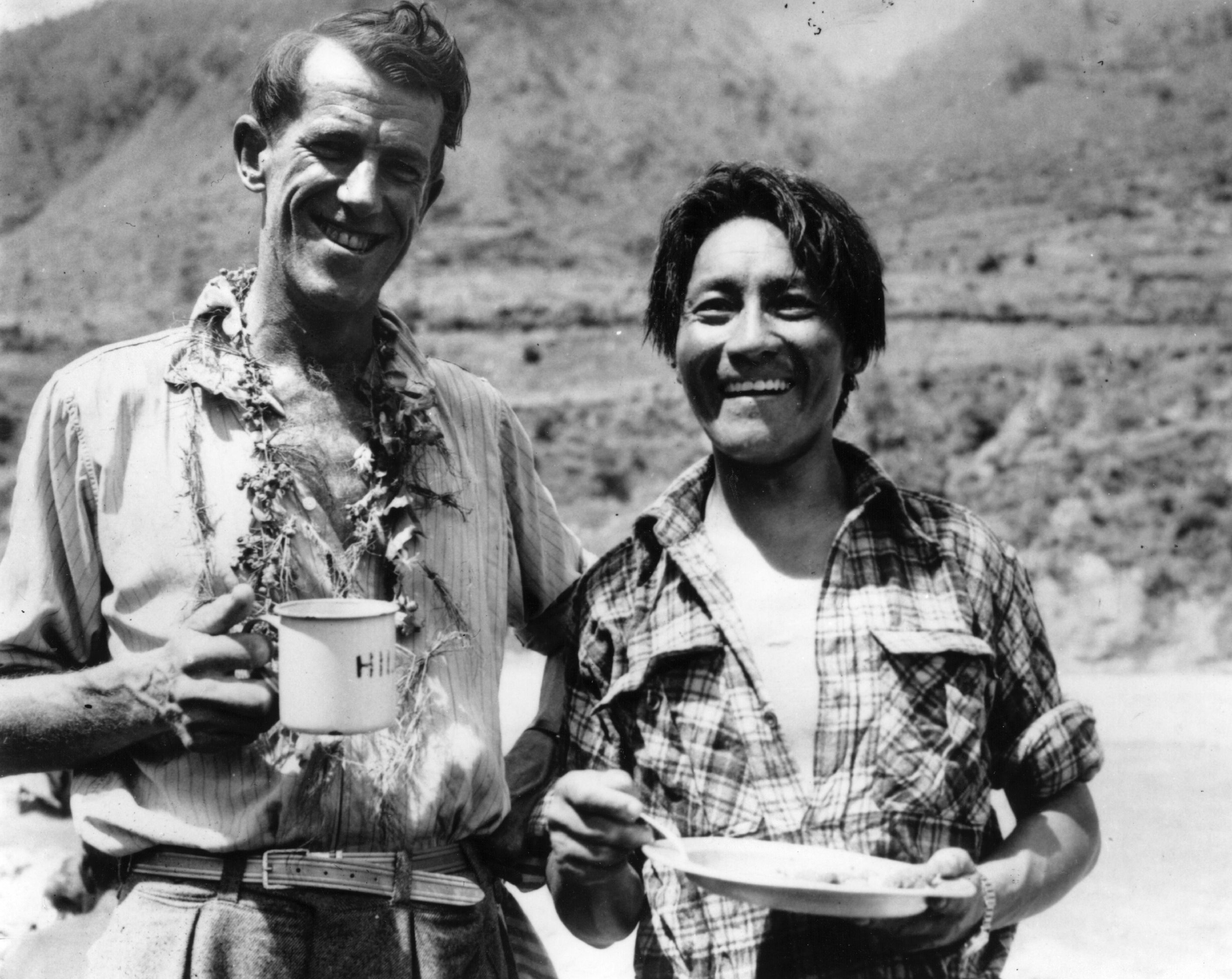

Sir Edmund Hillary didn’t exactly prepare for the Himalayas with side planks and hyperbaric chambers. The Kiwi was a beekeeper by trade, tasked with manning his family’s 1,400 hives. Daily chores on the honey farm formed the foundation of his physical conditioning, which he honed during stints in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and expeditions throughout the Southern Alps. He was an adept cross country skier, too.

When he and Nepali-Indian Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first people to summit Mount Everest, Hillary had to acclimatize to the altitude in real time. They set up progressively higher camps and spent significant time at each elevation before moving on up. What got Hillary and Norgay to the top, 70 years ago last week, wasn’t their physical prowess alone. And it certainly wasn’t their equipment, which was primitive compared to the gizmos available today. They relied on a combination of mapping and mettle. The duo studied the mountain ahead of time, then gritted their teeth and climbed it.

It likely would’ve shocked the duo, all those decades ago, to hear that by the 2010s, Chomolungma (the Tibetan name for the mountain), would be over-touristed. As training tenets, performance technology and flight patterns have proliferated far and wide, tens of thousands have made pilgrimages to the region’s 14 eight-thousanders. More than 6,000 mountaineers have now summited Mount Everest, alone. In some cases, this yearly rush has led to sobering storylines: like a traffic jam on the Hillary Step, shown in this unbelievable photo. Stuck in “conga lines” for days on end, people have died.

Even if climbing in the Himalayas weren’t such a crowded and complicated affair (the tradition’s relationship to local sherpas has been imperfect, to say the least), it’s also an extremely expensive one. To properly climb the Himalayas, you’re looking at least a $50,000 commitment, not to mention the employment freedom to leave work for two months at a time.

Bringing the Himalayas to Your Backyard

For most people, the Himalayas probably seem entirely out of reach. For a small few, they probably should be. But just about anyone can appreciate the absurd conditioning required to survive at the top of the world.

It got us thinking: instead of going to Mount Everest, how about bringing it to us? What does the casual, non-mountaineering adult have to do to get into an approximation of “Himalayan shape”? How do we prepare our lungs and legs? How might we deploy that fitness on more accessible ascents near our homes?

To be clear, if you were actually summiting Everest, you would need to have a command of: rope climbing, cramponing on ice and rock, rappelling with a heavy pack, using ascenders and jumars, crossing crevasses on ladders, etc. You can’t get very far without some serious technical chops.

But this blueprint is more concerned with simulating the physical rigors of a Himalayan expedition. It outlines the modern training wisdom that Hillary and Norgay would’ve put to good use — while retaining the resilience that they clearly had in droves. Here’s your best shot at attaining the athletic base of Himalayan climbers, via altitude simulation training, intense leg and core strength routines, cardiovascular endurance exercises and mental fortitude drills.

Is “Everesting” the Most Diabolical Endurance Challenge Yet?

The mountains are calling, and I must cycle. For 12 hours.Adventure Fitness

The bulwark of this regimen involves hiking, which is a great thing — it’s perhaps the single healthiest exercise available to the body. Lengthy “adventure hikes,” of the sort we’re discussing here, involve hours spent on one’s feet, weighted packs (a la rucking), elevation change, uneven terrain and time spent in nature. It’s longevity bingo.

Himalayan-hopefuls are known to commence their training cycles up to 12 months before traveling to Nepal, which affords them the time to progressively ramp up their hike time and distance. After all, outfitters aren’t exactly shy about conditioning requirements for Everest and the like: the training goal is 4,000 feet in less than three hours, with a 50-60 pound pack. For reference, New York’s Hunter Mountain and California’s Mount Diablo are both right around 4,000 feet.

Don’t fret too much about those numbers, though. It’s a hike. As workouts go, it’s endlessly modifiable. Get a read on how long it takes you to complete a 1,000-foot climb with a pack that’s 10% of your bodyweight, for instance. If that’s too easy, try doing it two days in a row. (Daily climbs are a hallmark of actual mountaineering). Fill your pack with something you don’t mind getting rid of at the top (water), so you can dump it and ease your descent back down.

If you don’t have any mountains in your backyard, make use of the largest hill you can find. March up it and back down — “Everest” cycling-style — as a form of HIIT training. That’ll light up your lower half and core. And if you don’t have any hills nearby, well, the treadmill is a special machine. Just be sure to ruck outdoors wherever, whenever possible, as you still want to challenge your footing on roots and rocks.

Outside of hiking, you’ll want to pack as much Zone 2 training into your week as possible. Make like a Norwegian cross-country skiing champion and spend five hours a week at 60-70% of your maximum heart rate. Running, cycling, swimming, whatever. Make it non-negotiable.

Lower Half Training

This is the meat and potatoes of this training scheme. Hikes are hard, but they’re beautiful. And you can always listen to a podcast during your Zone 2 work. Strength training circuits explicitly designed to torch your core and lower half, though — nothing glorious or relaxing there.

Still, they’ll serve you well in the hills, where strength, lateral mobility and balance are all paramount. Below, find two “mountain circuits” (the second leaning a bit more into unconventional moves and tools than the first), that’ll give you the extra power you need.

Mountain Circuit A

- Bulgarian Split Squats: This variation on the traditional squat introduces an element of balance and works each leg individually to iron out strength imbalances. Position your back foot on a bench or step and perform a deep lunge with your front foot. Complete three sets of 12 reps on each leg.

- Single-Leg Deadlifts: This exercise targets your hamstrings and glutes while challenging your balance and engaging your core. Holding a dumbbell or kettlebell in one hand, hinge at the hip and lift the same-side leg off the ground behind you. Complete three sets of 10 reps per side.

- Weighted Step-Ups: Step-ups mimic the action of climbing, and the added weight increases the challenge. Use a high step or box and hold dumbbells in each hand. Do three sets of 10 reps per leg.

- Sliding Lunges or Curtsy Lunges: These lunge variations require more balance and coordination and engage your hips and thighs in a unique way. For sliding lunges, stand on a hardwood or tiled surface with one foot on a towel or paper plate. Slide that foot backward into a lunge, then pull it forward again. For curtsy lunges, step one foot diagonally behind you and lower into a lunge. Complete three sets of 10 reps per side.

- Farmer’s Walk on Toes: This exercise mimics the act of walking uphill while carrying a load. Hold heavy dumbbells or kettlebells in each hand and walk on your tiptoes. The weights simulate a loaded backpack while walking on your toes strengthens your calves.

Mountain Circuit B

- Pistol Squats: One of the ultimate tests of leg strength, balance and mobility. Stand on one leg, squat down to the point where your hamstrings touch your calf, then rise back up. Do three sets of 5 reps on each leg.

- Lateral Box Walks: Mimic the side-to-side movements of navigating through rocky terrains. Find a box or bench, step up laterally, then down on the other side, and repeat. Perform for one minute then switch sides.

- Cossack Squats: This deep squat challenges the flexibility and strength of your legs. Begin in a wide stance. Shift your weight to one side, bending the knee until it’s over your toes, and keep the other leg as straight as possible. Do three sets of 10 reps per side.

- BOSU Ball Squats: The unstable surface of a BOSU ball makes for a unique balance challenge. Stand on the flat side of the ball, lower down into a squat, then rise back up. Do three sets of 10 reps.

- Tire Flips: This exercise is excellent for developing explosive power, strength and cardiovascular endurance. Flip a large tire (with proper form) for a given distance or time. Do three sets of 10 flips.

It’s Never Too Late (Or Early) to Try Tai Chi. Here’s How.

The gentle art is perfect for lifelong fitnessAltitude Acclimatization

A brief aside on NCAA Division I Cross Country, if you will. The sport’s top teams are about what you’d expect — Texas, UNC, Oregon, Princeton, etc. But one of its perennial contenders, Northern Arizona, might sound unfamiliar. Why is NAU so good at running? Well, its athletes train in Flagstaff, Arizona, in pine forests that are perched nearly 7,000 feet above sea level.

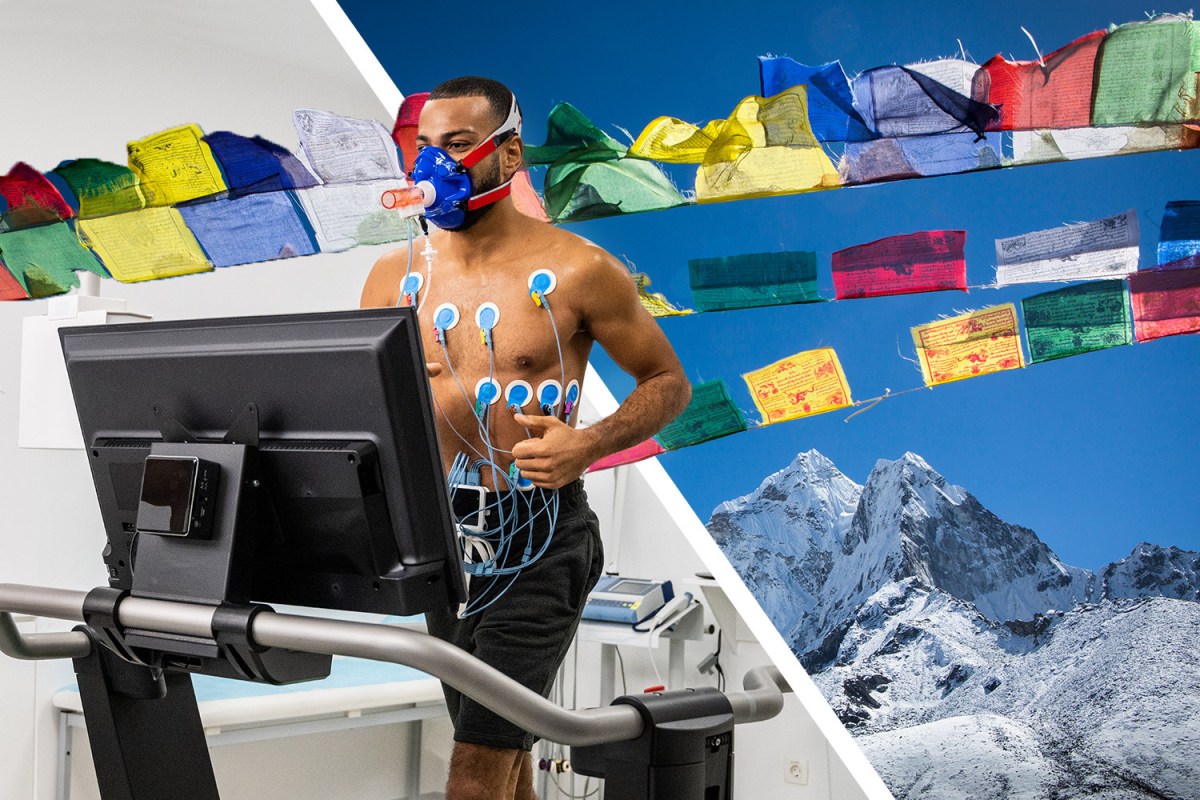

Training at altitude is believed to help spur the production of erythropoietin (also known as EPO, also known as the hormone that Lance Armstrong was injecting into his bloodstream in 1999). It boosts one’s production of red blood cells, in turn, and helps you transport oxygen more efficiently. In the mountains, this process proves absolutely critical; there’s less oxygen in each lungful of air, because of the decrease in air pressure. For years, individual athletes and teams alike (here’s the French national football team training in the clouds at St. Moritz) have leveraged altitude training to their advantage. You can do some real damage once you get back down to sea level.

Something to keep in mind: programs for elite athletes consider 5,000 feet the starting point for high altitude training. Which means that if you don’t live in Colorado Springs, you might be out of luck. There are a number of sea level solutions, though. Some are more effective than others, and some are simply more expensive:

- Altitude Masks: These things are very accessible. You can get one from Amazon for $40 right now, and have probably seen someone wearing one at the gym this year. The reviews on them are fairly mixed, tough. They can’t actually lower the oxygen content of the air, obviously — they just restrict the amount of air (and therefore oxygen) that you inhale during exercise. This will strengthen your respiratory muscles, over time, but fall short of increasing RBC production.

- Intermittent Hypoxic Training Devices: Huge level-up from altitude masks here. IHT machines, which can run up to a few thousand dollars, modulate the oxygen content of the air you breathe while exercising, and help your body adapt to lower oxygen levels. Use under the guidance of a licensed professional is usually recommended, as improper usage can have negative effects. That said, you can purchase one for your own, to use in tandem with a treadmill or stationary bikes. Reach out directly to brands like Hypoxico or Mile High Training. MHT actually allows you to rent an E-100 Altitude Training Generator for a month, at $600. The system goes up to 12,500 feet for training, and 21,000 feet for intermittent hypoxic breathing sessions — sedentary intervals where you’re exposed to extremely thin air for five-minute stretches.

- Altitude Tents: Another complicated apparatus. These tents range in price from $1,000 to $3,000, and yes, you literally sleep in them. If you don’t have a significant other — and don’t plan on courting one anytime soon — go full steam ahead. You’re sleeping in a compromised oxygen environment, which, in theory, can help increase red blood cell count and improve your body’s efficiency in using oxygen. But it will make sleep uncomfortable, at least at the outset (it’s humid in there), and if you live at sea level, it will be difficult to retain those nightly benefits during the day.

- Other Options: Look into high-performance training centers and medical research facilities in your region that offer realistic simulations of high-altitude conditions. Just note that access is often limited and often quite expensive (think hundreds to thousands of dollars per session, depending on the facility and the duration of the session). They’re beneficial for elite athletes or mountaineers with a hefty training budget. At that point, though, you might just want to move to the mountains.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.