Conspiracy theories are far from a contemporary phenomenon, but conspiracy theories have occupied a much greater space in the national psyche in recent years than any time in living memory. While it can be jarring to see conspiracy theorists storming the Capitol or popular athletes embracing some of the most unsettling forms of conspiratorial thinking, it can be useful to understand the historical roots of this line of thinking.

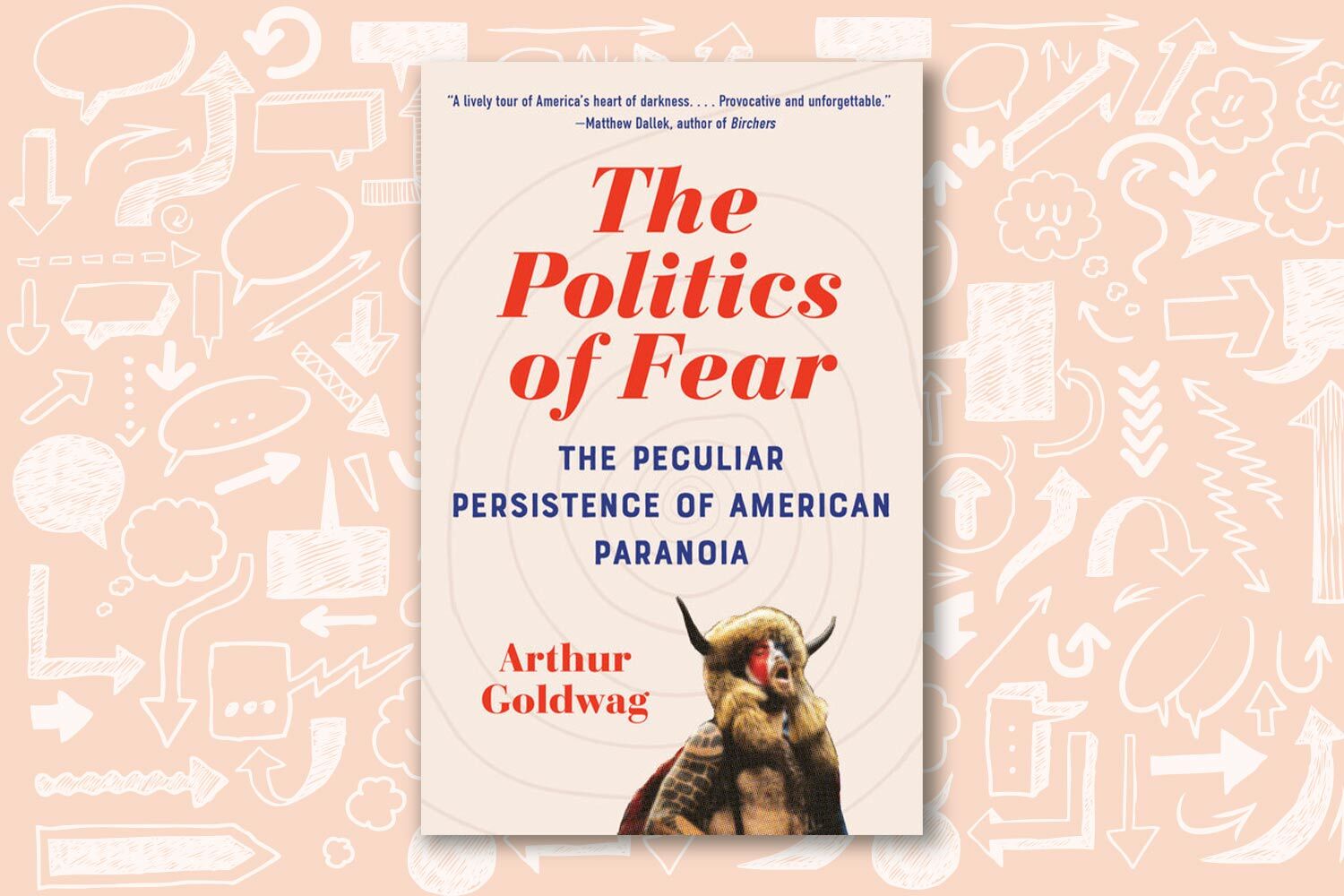

That’s what Arthur Goldwag has done in his new book The Politics of Fear: The Peculiar Persistence of American Paranoia. Goldwag has written several books over the years about subcultures, paranoia and some of the bleaker places conspiracies can take people. His new book is a compelling and disquieting look at both the current state of conspiracy theories in the United States and some of the historic roots of those beliefs.

InsideHook spoke with Goldwag about his long career exploring paranoid thinking and radical groups, the uncanny staying power of certain concepts and what the future of conspiracy theories might bring.

InsideHook: Over the years, you’ve written a few books on cults and conspiracies, of which this is the most recent. How did you first get into that as a kind of a beat as a writer?

Arthur Goldwag: It started totally by accident. I had published a book called ‘Isms & ‘Ologies about 20 years ago that was kind of an encyclopedia of big ideas in the arts and politics and science. It was a book to browse. I got into conversations with the publisher about what I could do next. I had some ideas, and they suggested a book about non-canonical ideas, a book about conspiracies and superstitions — and we narrowed it down to Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies. When I was a teenager, I used to read UFO books. I went through a phase where I was reading books about assassinations and so on. I assumed that it would be fun — and then I got into some very dark places right away.

When the book got released, I found that I had really stirred up a hornet’s nest. It wasn’t a huge book, but because of the internet it went to all the right places to get people mad. I was suddenly hearing from 9/11 truthers and John Birchers, and I started to realize that there was this shadow side to American culture, American politics and American ideas. I wrote another book called The New Hate, which went into the history of hate movements, which was published in 2012. It was four years too soon.

Was there a sort of a moment where you realized that this thing that had always been on the fringes of American society has suddenly become much more central to American life?

Yeah. It was the Trump election. I mentioned Trump in The New Hate. I mentioned him as a birther. I don’t think I wrote more than a paragraph about him. But my argument in The New Hate was, look, nobody important believes this stuff. These are fringe ideas, but politicians use them and they use them to activate people. And come on, don’t they know better? Shouldn’t we all know better?

I’m not a professional journalist. I’m a freelance writer. I came out of book publishing. But after the book came out, I started doing some journalism for the Southern Poverty Law Center. I would go to hate group meetings — I never got press credentials. I would sign up and go there and not tell them who I was, and it could be pretty awkward because they could tell that I wasn’t one of them. But I would take notes and so on.

I was always struck by how marginal these people are. I mean, there were never a lot of people at these meetings. The people there weren’t important people. They were mad at the Republicans for not listening to them more. I remember I was at this neo-Nazi meeting when the Republicans were doing the postmortem of the 2012 election. And the neo-Nazis were upset about that: “Why are they trying to bring people of color into the party? They should be strengthening their white base.” And then all of a sudden, it was right in the mainstream.

One of the meetings that I went to was the National Policy Institute, which was Richard Spencer. Right after the Trump election, there was this thing that went viral where Richard Spencer is leading a packed room in chants of “Hail Trump, hail our people.” And I remember thinking, “Oh my God, this is real.”

I had stopped writing about this stuff because I found it so depressing. In 2020, I wrote a proposal for a book. I thought, “I’ve actually been a part of this conversation years ago. I think the public actually would benefit from somebody shedding this kind of light on these things.”

And even then I got it wrong because my argument was, look, Trump is going to leave office. He’s going to disappear and we’re going to forget about him in a year or two. I don’t want people to forget. So I started writing this book and Trump wasn’t going away. I had to rethink my whole approach to it.

In The Politics of Fear, you discussed Umberto Eco and I was reminded of his novel Foucault’s Pendulum a lot at various points when reading your book. You also brought up a group called the Paladists, who I was not at all familiar with before I read this. Can you talk a little bit about them?

Well, the Paladists were the demonic Masons. There was a guy in France, Léo Taxil, who wrote a whole series of books in the 1890s about these dark Masons that were demon worshippers. He would call press conferences and write these explosive articles. And then one day he called a press conference and said, “You know what? I made this all up. And I made this up to expose the Catholic Church because they’re pushing this stuff because it makes them more powerful.”

I wanted to make the point that you can put out any of this crap there if it serves them and they’ll believe it. Then it turned out that he had this whole history of putting out fake stories. Anyway, no one had to debunk this conspiracy anymore. The creator of it had debunked it. But you can look up Paladism now and people will say, “You know what’s this incredible thing? There are these demon-worshiping Masons that are in powerful places.”

One of the points I made throughout this book is the stickiness of the irrational. It’s so sticky because it serves a purpose for people. It organizes the world in a way that makes them feel like they have some control. The people who believe this stuff, it’s not that they’re stupid. It’s not that they’re crazy — although I wish they were more rational. It’s that they’re unhappy.

When you look at this phenomena of Trump worship, I don’t mean to tar every conservative person with the same brush. I don’t mean to say that everyone that goes to church is a Christian nationalist. I don’t mean to say that everyone that wants to pay less taxes and votes Republican is a proto-fascist. I don’t believe that. But the true believers, things have not gone well for them. Trumpism has a real discernible geography. And it’s not in cities. It’s in rural places. It’s in the left-behind places. And the people who follow it more or less are people that a generation ago were more or less thriving in blue collar lines of work that don’t exist anymore.

If you look at the history of American and European conspiracy theories and populism, it tends to be when times are bad. There’s been an economic crisis. There’s been a war. Somebody’s been displaced, and somebody gives them a story. There aren’t that many stories. It’s an archetypal story. The Satan story is an archetypal story; it explains things for us.

In The Politics of Fear, you brought up the fact that there was a boom in conspiracies in the years following World War II. Do you think there’s one thing that led to the rise of conspiracy theories now, or is the sum total of everything from the Great Recession to deindustrialization to multiple wars?

I’m not a conspiracist myself, so I don’t want to reduce everything to one or two causes. There are always exceptions. There are people that are worried about their children. And there are also people that are worried that their kids don’t want to stay where they live. They want to go to college or they want to go to the city and they’re going to lose them. They’re going to come back and they’re going to belong to a different culture, and maybe they’ll meet somebody with a different color skin or a different religion or they’ll leave religion altogether.

It’s that fear of losing this thing that you used to have. And it’s that fear of loss that I think drives so much of historical conspiracy theory. We forget this. Another big point I make is how rabidly anti-Catholic America was, as a country, for so long. It really has changed. There’s always been a lot of casual anti-Semitism in America, even before there were very many Jews in America. But the government in America has never been anti-Jewish. And you go to Europe and Jews weren’t citizens in most countries until the 19th century, late in the 19th century in some cases.

The strain of anti-Catholicism in American history was one of the things in the book that I was completely unfamiliar with before reading it. I was a little familiar with the Acacians being displaced in New England and Canada, but I wasn’t aware of the overarching history behind that. When did you first start to notice that as something that has had a larger influence in North American history?

I’m not sure when the “Aha!” moment was. Well, I kind of do know. I wrote an article about Anne Hutchinson, and it was about something completely different. It was about antinomianism in a field that has nothing to do with this book. But what I was reading about was the early Puritans’ terror of anarchy, and I started reading about the wars of the Reformation, and they were unbelievably bloody. Americans don’t have that cultural memory, because the original Puritans came here to get away from that.

The fear that they brought with them was of the Catholics and the Catholic wars. And another thing that brought it home was the anti-Catholic elements in the French and Indian Wars. They weren’t called the French and Indian Wars in Europe. That was really a worldwide conflagration. It was the First World War. The stuff in America was a sideshow.

One of the Intolerable Acts that brought about the American Revolution was the acceptance of Catholicism in Canada. And the Americans were so anti-Catholic that that was one of the things that set off the revolution. When I was writing The New Hate, I read a lot about the stuff that John F. Kennedy was up against, and the elections in the 1920s, and the Klan. Where did this stuff come from? Well, it was always there. But because it’s not respectable, and because these are always fringe ideas, they disappear from the discourse. And having the internet now, and having social media, suddenly these fringe people have the exact same presence that mainstream people do.

When you study conspiracy theory, you realize that so much of it is just cut and pasted from old books. It’s not that original. And a lot of the anti-Masonic stuff was cut and pasted from anti-Jesuit propaganda. A lot of the anti-Jewish stuff was cut and pasted from anti-Masonic stuff. A lot of the anti-Islamic stuff that came out after 9/11 was cut and pasted from anti-Semitic stuff. People reuse this stuff because it’s so primal and so present.

Aaron Rodgers for VP? He Won’t Be Getting Votes From the Jets.

Speaking “continuously” with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has nothing to do with footballYou brought up the fact that, from your research, the first occurrence of the phrase “conspiracy theory” was in 1863. Do you think there’s anything about that particular time that was germane to conspiracy theories more broadly?

Absolutely. I write a little bit in the book about the “slave power” theories. The abolitionists, some of them, were very educated, serious thinkers. But there was a fringe in that too. And you have these crazy books that assert that basically all of American history has been the slave power’s attempts to enslave not just Black people, but white working people. And then the war happens. And I mean, it’s a cataclysm. So many people died. The infrastructure in the South didn’t really recover until late in the 20th century. It’s a disaster. And it also turned the social order upside down.

When we read history, it’s history, we turn it into a story already. But at the time, they didn’t know what was going to happen. And the world really was falling apart. After the Civil War, we talk about the Gilded Age, people tend to forget that the Gilded Age is laid on top of a 30-year depression. But at the same time that we were turning out all these billionaires and industrializing our cities like mad, there were a lot of hungry people and a lot of farms going under, and a lot of despair. And the Silver Movement and rural populism, these were huge movements. And they’re just not at the top of people’s minds, unless you really go into history.

In your reading about conspiracy theories, have you found any kind of way to sort of inoculate or boost people’s susceptibility to some of the more toxic conspiracy theories out there?

I’m pessimistic about efforts to reason with people, but I don’t want to lose people. What I do know is that these things wax and wane. In my book ‘Isms & ‘Ologies, one of the terms I define that I like is meliorism, which is the belief that things are getting better, albeit very slowly. I tend to think that we are getting smarter and juster as a society. What we’re dealing with now is a backlash. What we’re dealing with now is an oscillation.

It’s very scary because it doesn’t usually take place at the top of the political order. The stuff is usually in the middle of the political order. What’s happening in presidential politics is terrifying. But in the long run, I think that humanity has gotten wiser and less violent. And when you immerse yourself in the stories of the wars of the Reformation, for example, we’re not that bad now. I don’t want to be too rosy, but some of these terrible things that have happened in the past I think will not happen again. At least, that’s my hope.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.