America, this sad and silly country, has become an oligarchy ruled by comic-book nerds and profit-hungry producers; for the last 15 years, we’ve been force-fed a bland pâté of the same old stuff, a constant deluge of movies rife with muscular, attractive and utterly, unwaveringly valorous saviors clashing with a litany of increasingly listless bad guys threatening to destroy the computer-generated universe. It’s all so boring.

It wasn’t always like this. Thirty years ago, Tim Burton‘s Batman Returns — a brooding, batty, bizarre melange of grand guignol horror and slapstick cartoonish ridiculousness — was released upon eager moviegoers, who, in typical mainstream moviegoer foolishness, just didn’t get it. They wanted something friendlier, something “for kids,” perhaps, and parents ran pearl-clutching out of the theaters. (This hostile reaction is why we consequently got Joel Schumacher’s flamboyant, family-friendly films.) But time has been kind to the film, which is, I think, still the apogee of the genre, a rare example of what a comic-book movie can be in the hands of a daring filmmaker. Burton’s film is a wonderfully dark monster flick, really nasty stuff. The ghoulish Penguin, a monstrous mutant rather than the eloquent bird-obsessed burglar of the comics, plans to kidnap and kill all of Gotham’s first-born sons and drown them in sewage. Compare this insidious infanticide scheme to the perpetual threat of annihilation in the Marvel and DC films, where the stakes are so absurdly high they cease to inspire any kind of awe. The Penguin wants to murder children. Children! Isn’t that so much better?

Batman Returns is a mean bastard of a movie. (The film opens with two upper-crust parents tossing their baby carriage into a stream as the bundle of joy squawks.) There was a lot of talk when it came out that it wasn’t in the real spirit of Batman, that Burton betrayed a beloved character by making the film so lugubrious. But Batman Returns is very much a Batman movie: the gothic monster movie vibe harks back to the run of titles written by Dennis O’Neil and drawn by Neal Adams in the ’70s (e.g. their issue with the Man Bat), while the Penguin’s ploy to become Mayor is lifted from an episode of the Adam West show. But the biggest issue people had with the movie is that Batman kills people — and he even seems to like it. (Notice the slight furling of his lips into an insinuation of a wicked smile as he puts a ticking time bomb in a clown’s pants.) But back in the 1940s, Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s Batman did kill people. In his very first solo issue, Batman gunned-down a henchman with a machine gun, threw another off a building and hanged another from his Batplane (“He’s better off this way,” Batman says). And 1940 was a particularly bloody year for Batman: he impaled a Chinese swordsman, threw an American disguised as a Chinese swordsman out of a window and crushed a crowd of Mongols with a Buddha-esque statue. Batman stopped killing people because the suits who made money from sales decided the comic would appeal to a wider audience if Batman was a bit nicer. But what separates Batman from his more goody two-shoes peers is that he is dark; he is violent; his entire superhero identity is built out of trauma. He’s the most human of heroes, which means he’s the most flawed, the most complicated.

As with Burton’s previous Batman film, Michael Keaton plays the Caped Crusader. He has a sanguine, sotto voce intensity, eyes wreathed in black makeup and that stiletto stare. He remains, for me, the definitive Batman. (Keaton’s comedic chops are better used here than in the previous film; take, for instance, his delivery of the line, “Eat floor.” Pause. “High fiber.”) Think of Christian Bale and his rasp, how he’s an unequivocal, honorable defender of justice, a real good guy who believes in Gotham, who believes in right and wrong. Yawn. Keaton’s Batman/Bruce Wayne is clearly a troubled guy (to Nicholson in the first film: “You wanna play? Let’s get nuts!”), not the platonic ideal of an American man. He’s a little crazy, as Batman should be. You can see subtle hues of Keaton in Ben Affleck’s Batman. Affleck is comically jacked (he has the same wide build as the character in Batman: The Animated Series) but worn down, a crestfallen Caped Crusader, a tinge of gray in his hair and that glint in his eyes a little dulled. And he’s violent, like Keaton’s, albeit in a different way. He’s nearly superhuman in that (admittedly really awesome) fight scene in the warehouse in Batman Versus Superman, the hunky hero cracking skulls and shooting people and stabbing a dude right in the chest. You can see the craziness, the anger. Affleck kicks ass; Keaton’s Batman is more stoical, more still. He stands still and looks cool. He doesn’t do much hand-to-hand fighting (though he does light a guy on fire with his Batmobile). But the most distinct difference between Keaton’s Batman and the subsequent men to dawn the cowl is his Bruce Wayne, who’s almost an Everyday Guy rather than an Armani-wearing one-percenter, which is important because Batman is not supposed to be just another privileged trust-fund kid. He doesn’t flaunt his wealth — he may even feel guilty about it — but he uses it to help people by funding his crime-fighting operation. He is, in this sense, a philanthropist. When Alfred brings Bruce a fancy bowl of soup, he takes a spoonful and spits it out, saying it’s cold. Alfred responds by telling him it’s Vichyssoise, it’s supposed to be cold. This is not a billionaire who spends much time with society types.

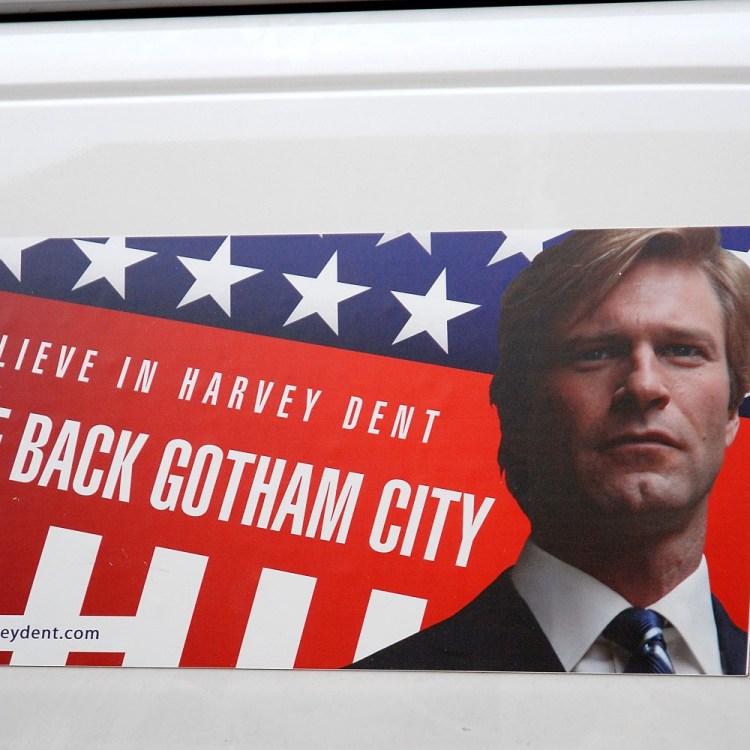

Bruce Wayne’s altruistic affluence is juxtaposed with the nefarious Max Shreck (named after the actor who played the horrifying Nosferatu in Murnau’s seminal silent film), a psycho in a pinstripe suit. Christopher Walken, with his gray shock of hair rupturing from his head and that odd delivery of his, imbues the odious Shreck with a theatrical sociopathy, all smooth talk and sinister schemes to get richer. Shreck sees in the Penguin a chance to wrangle control of Gotham, so he manipulates the fish-eating freak to run for Mayor. (My favorite part is when the Penguin waddles downstairs, chomping on a raw fish, and Shreck surprises him with a committee for his mayoral campaign. Someone quips to the Penguin that there must not be any mirrors in the sewers, and the portly puffer retorts, “It could be worse. My nose could be gushing blood,” and he bites the guy’s nose off.) Danny DeVito devours the scenery, gnashing it with those dilapidated, black-oozing teeth; he’s clearly having a blast, something that is sorely lacking in today’s glut of comic-book properties. Josh Brolin is so damn serious in the Avenger movies, and Zack Snyder’s films are so portentous, bloated with testosterone and braggadocio. Batman Returns is fun; it has a sardonic sense of humor. And its anachronistic world, obviously shot on sound stages, with all that fascist-inspired architecture stretching up out of the steaming streets and up towards the starless night sky, is free from the constraints of time. It could be taking place now, or a long time ago, or at some point in the future. The Penguin uses a quill pen, and Batman uses compact discs. The film will never age.

DeVito is the main villain, and his performance is gleefully histrionic, and Walken does his own share of Walken-isms, but Batman Returns belongs to Michelle Pfeiffer. Her Selina Kyle is initially a sad-sack secretary, dismissed and abused by Shreck, anxious and with no self-esteem. When she comes home to her pink apartment, with its dollhouses and stuffed animals, she says, “Honey, I’m home. Oh, I forgot, I’m not married.” It’s funny, and piteous. And yet there’s something simmering just beneath the surface, pent-up anger that can only inevitably manifest in violence. You can’t keep kicking someone around without them eventually kicking back. Consider the scene when she wrecks her apartment, smashes and slashes and spray-paints, the crazed look in her eyes. After she sews her skin-tight leather suit, tar-black with stitches like scars, we get our first glimpse of Catwoman, a far-off static shot gazing into her window, the neon lights reading HELL HERE, and she appears, her voice now sultry, confident. She’s found herself.

Compare Pfeiffer’s Catwoman to any of the female characters from the MCU or DC movies. Take, for instance, Gal Gadot, who is not a very good actress; she plays Wonder Woman with a stale valiance, her morals never in question, her motives wholly venerable. She is a good guy, no question about it; this dauntless heroism isn’t interesting because there’s no conflict, no internal struggle. Her allegiance is never in question. And the ladies of the Marvel Universe are similarly boring, just a bunch of righteous defenders of humanity, always doing the right thing. Pfeiffer’s Catwoman is, like Batman, born out of trauma: Shreck pushes her out a window, and, as she lies there in the snow, 20 stories down, a drove of alley cats descends upon her, licking her, nibbling her, her eyes twitching and Danny Elfman’s strings shrieking, and then she awakes, transformed. She wants revenge against Shreck, against the city, which temporarily aligns her with the Penguin, and yet we see, in the scenes with Selina and Bruce, that she isn’t a villain but a tragic victim who is standing up for herself. Life’s a bitch; now so is she. Pfeiffer and Keaton have sexy chemistry. Consider the scene where she lays on top of him and intones that mistletoe is deadly if you eat it, or the repeat of that line, at the lavish masquerade ball, where they realize each other’s alternate identities and she looks, at once, shocked and not, a little confused, almost like she wants to lick his face. Nothing in today’s deluge of IP products has anything even resembling this sexuality. The current crop of superhero movies are sexless, neutered. They’re cowardly.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.