Living in the world means reckoning with contradictions even at the best of times, but the current decade has abounded with them even more than usual, or so it seems. The best books of 2023 seemed to draw inspiration from that, with their central arguments exploring the paradoxes inherent in living in such a time. Whether chronicling a (fictional) writer asked to collaborate with an algorithm or a (real-life) musician reckoning with their own ambition, these 10 books explore paradoxical conditions in the worlds of art, technology and politics.

Not every book has to change the way its readers view the world, but these 10 books do provide that experience. Some of them use fiction in order to reckon with the most urgent issues of the day; others find unexpected facets in names you might recognize from the news (or your record collection). And they’re compelling, absorbing books in their own right —literature that helps to bring the complexities of the world of 2023 into sharp focus.

Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World

For long stretches of her career, writer Naomi Klein has found herself confused or conflated with another writer who shares her first name and some of her areas of concern: Naomi Wolf. What was once a source of some amusement for Klein took a turn around the time when the pandemic began and Wolf doubled down on conspiratorial thinking and anti-vaccine activism. Doppelganger begins as Klein’s chronicle of Wolf’s ideological shift — but that’s far from all it’s about.

Instead, Klein uses the concept of the doppelganger to muse on a host of urgent subjects, from climate change to digital avatars — and what she refers to as “a feeling of near violent rupture between the world of words or the world beyond them.” There’s also a thoughtful look at contemporary politics and an incisive take on Philip Roth’s stunning novel Operation Shylock. Doppelganger pulls off the impressive feat of being both extremely specific in its focus and being ultimately about nearly everything; it succeeds at both tasks.

Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon, editors, Critical Hits: Writers Playing Video Games

We’re a long way from the time when Martin Amis’s 1982 book about video games felt like a strange curiosity in the literary world; now, plenty of acclaimed writers have turned their time gaming into a source of inspiration. (And some, like Tom Bissell, have crossed over into working in the gaming industry itself.) All of which makes this wide-ranging anthology from Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon feel like it’s arrived at the ideal moment.

What will you find in Critical Hits? Writers like Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and Alexander Chee contemplating the ways that the games they’ve played have shaped the way they think of themselves and their family, for one thing. Charlie Jane Anders explores the subgenre of movies about people playing video games; J. Robert Lennon observes generational shifts in the way people game. The range of approaches to the subject is as vast as life itself — which is arguably the point here.

Yepoka Yeebo, Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World

Earlier this year, I interviewed journalist Yepoka Yeebo about Anansi’s Gold, her book about John Ackah Blay-Miezah, a charismatic con man who convinced a stunning array of notable people from around the world that he had a direct connection to a stash of riches hidden away by a former Ghanaian head of state. “I thought I was writing a caper, and I thought it was going to be fun and lighthearted,” Yeebo told me — and it’s not hard to imagine an alternate version of this book that emphasizes those aspects of Blay-Miezah’s story.

Instead, Yeebo goes deeper and finds the tragedies that piled up in Blay-Miezah’s wake — and those that set the stage for his misdeeds. Anansi’s Gold incorporates Cold War politics, the U.S. civil rights movement and much more into a wholly engaging narrative — and one with consequences that are hard to shake when you’ve reached the final page.

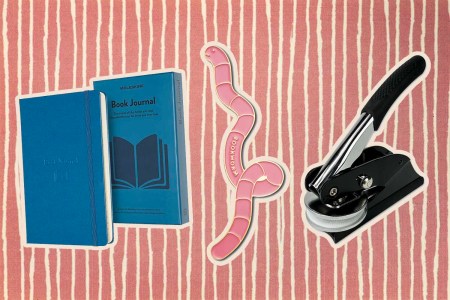

Sean Michaels, Do You Remember Being Born?

There’s been a lot of discussion of AI and machine learning in 2023, though the areas in which this technology has been in the spotlight may not have been the ones that were hinted at around this time last year. The same is true for books around AI; those that I’ve found to be the most interesting are those that don’t take the obvious angles on their subject. See also: Matteo Pasquinelli’s The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence, a thoughtful look at centuries’ worth of thinking that underlies some very contemporary debates.

In Sean Michaels’s novel, a beloved poet named Marian Ffarmer is offered a unique assignment: collaborate on a book-length poem with an algorithm. The poet is skeptical, but the money being offered is staggeringly good; cue a surreal clash of cultures, as an aging writer ponders her family and her approach to art as she spends days in a room in dialogue with a collaborator who may or may not be a sentient form of intelligence. Michaels rarely goes where you expect, and the sense of a prodigious artistic talent placed in a situation entirely new to them gives the book a disorienting and engaging energy.

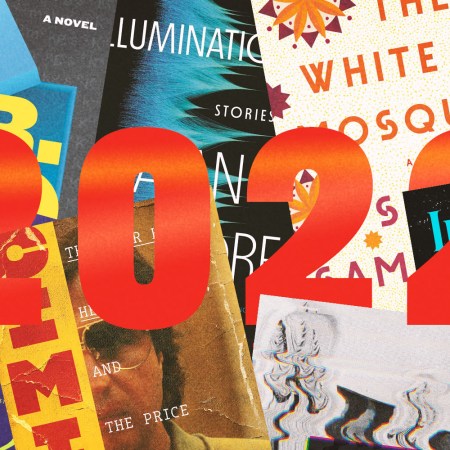

Kerry Howley, Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs: A Journey Through the Deep State

Kerry Howly’s first book Thrown gave readers a firsthand account of what it’s like for a trio of up-and-coming athletes seeking their fortune in the world of mixed martial arts. On the surface, Howley’s followup Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs doesn’t have much to do with her earlier book; this one is about the intelligence community, whistleblowers and paranoid thinking — and yet the two share a couple of qualities that suggests that they’re closer than you might think.

For one thing, Howley writes about the complexities of conflicts well, whether it’s two fighters facing off in a ring or someone deciding to leak classified information. For another, she has a penchant for meticulously chronicling the precise details of interpersonal interactions; in Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs, that includes a harrowing description of several events in the life of whistleblower Reality Winner. Howley’s talent for storytelling recalls the great John McPhee — both in terms of creating empathy for her subjects and for presenting complex issues in innovative yet eminently readable ways. And this is essential reading, whether you’re concerned about the book’s subject matter or are simply searching for an immersive read.

Kashana Cauley, The Survivalists

It’s only a few pages into Kashana Cauley’s debut novel The Survivalists when Aretha, the New York-based lawyer at the heart of this book, meets Aaron, a charismatic small business owner whose work takes him all over the world. It’s a charming meet-cute — except for the fact that Aaron and his roommates also own a copious amount of guns and have a bunker in their backyard in case society collapses.

Cauley doesn’t shy away from engaging with big topics here — race and guns in contemporary America play especially important roles as the novel develops, and Aretha’s frustrations with her high-pressure corporate law job might inspire sympathy stress from readers who have been in similar positions. But The Survivalists is also about other things, from the paradoxes of contemporary dating to the joys of a well-made cup of coffee. The ambitious story being told will leave you thinking, but it’s the small details that’ll make you return to this book again and again.

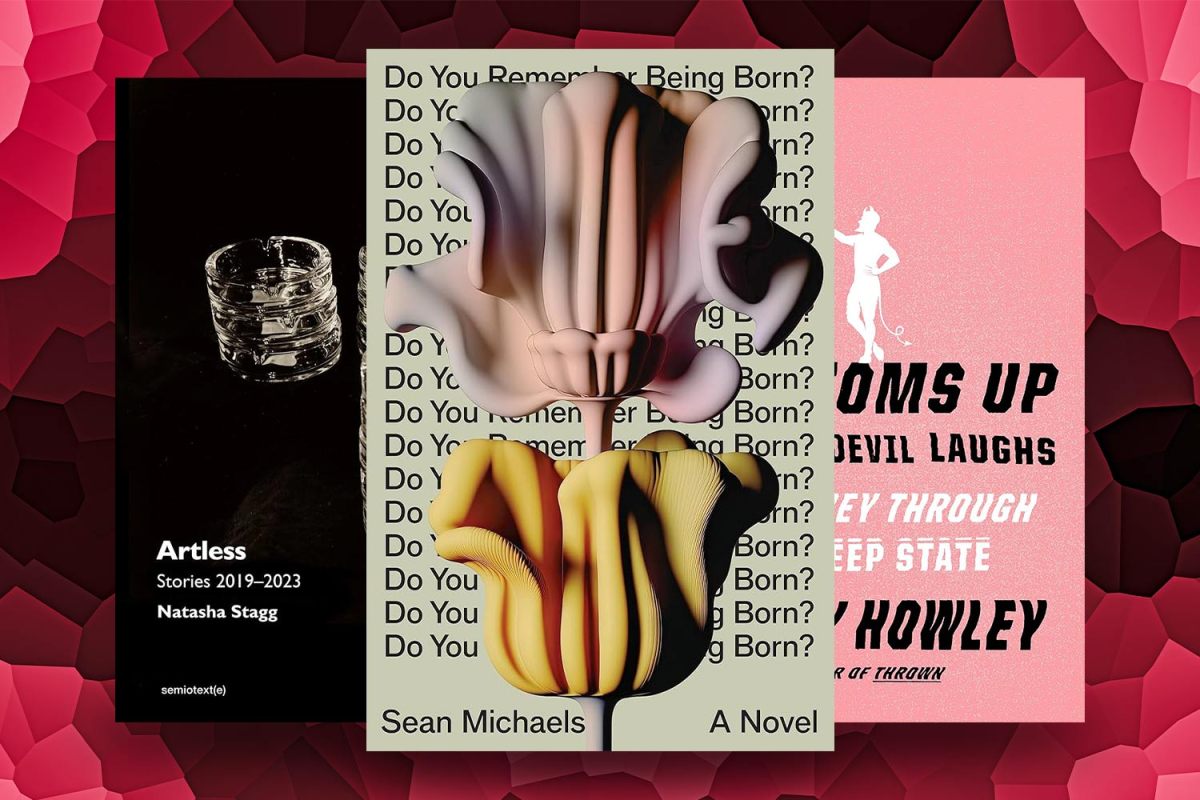

Natasha Stagg, Artless: Stories 2019-2023

Like a lot of the books on this list, Natasha Stagg’s Artless is a lot of things. Readers of this collection will find writings on a host of subjects, from the nature of fame to the challenges of urban life in the early months of the pandemic. More literally, there’s also fiction and nonfiction found between these covers, with no formal delineation given between the two forms. Early in the book, Stagg writes that this “elaborates on and possibly contradicts what I’ve written before.”

That blurring of forms and revision to earlier work is very much intentional; instead of easy divisions, readers are treated to Stagg’s literary voice in a host of different contexts. “I think everything you write has a purpose, and if you understand the purpose and the audience, you shouldn’t veer too far from what its intention is,” Stagg told AnOther Magazine in an interview this fall. It’s a distinctive ethos, and one well-represented here. And along the way, Stagg raises bold questions about art, work and identity.

The Best Gifts for Readers That Aren’t Books

Because under no circumstance should you buy them a book

Kelly Link, White Cat, Black Dog

Somehow, it’s been over 20 years since the publication of Kelly Link’s first collection, the revelatory Stranger Things Happen. After reading that collection for the first time, I was dazzled by Link’s storytelling and mystified as to how she made the strange connections at the heart of her fiction. Several books later, she’s still doing it, blending an immersive sense of place with dream logic and folktale evocations to create something entirely new.

It’s worth mentioning that this collection contains “Skinder’s Veil,” a story that’s near the top of my list of favorite Link short stories, which means it’s also near the top of my list of favorite short stories, period. It’s about a guy who agrees to house-sit a remote cabin in the woods with a handful of very precise rules; what happens next is both unnerving and miraculous. And, would you look at that: “unnerving and miraculous” is also a perfect description of this collection.

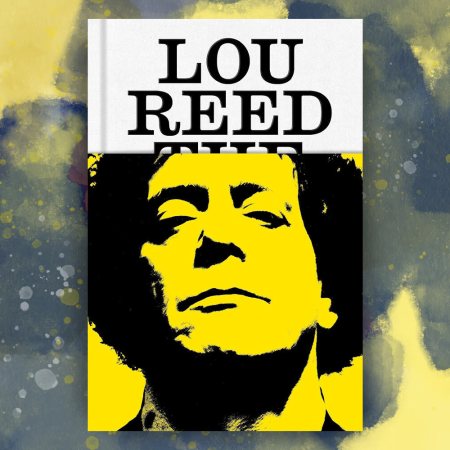

Will Hermes, Lou Reed: The King of New York

Will Hermes writing a book about Lou Reed is a perfect fusion of biographer and subject — and not always in the ways that you’d expect. That the writer of Love Goes to Buildings on Fire has plenty to say about Reed’s music and his work with a host of collaborators isn’t a shock. (“When he let people in to work with him, I think he made his strongest work,” Hermes told InsideHook in an interview around the book’s publication.)

What makes The King of New York unexpectedly moving can be seen in the last three words of the book’s subtitle. In the first half of Hermes’s book, he chronicles Reed’s search for stardom — on the level of, say, his occasional collaborator David Bowie. And yet that’s not where Reed’s career took him. The bittersweet part of Lou Reed is that it’s the story of a musician seeking rock stardom and ultimately becoming more of a cult hero; the genuinely moving part of Lou Reed is that it’s also about why a cult hero isn’t such a bad thing to be.

A. V. Marraccini, We the Parasites

The best critical writing can make you rethink a given book, movie or album. Sometimes, though, the best critical writing makes you rethink the very act of reading, watching or listening. That’s the case with A. V. Marraccini’s bravura collection We the Parasites, which abounds with rich metaphors and visceral imagery (the word “parasites” is in the title for a reason) alongside thought-provoking arguments about art and desire.

“I don’t like the idea that criticism isn’t significant because it’s not the primary work, or that it’s not significant because it uses referentiality,” Marraccini said in an interview with Full Stop earlier this year. “What literary work doesn’t, or isn’t?” It’s a sentiment worth pursuing — and you’ll find a lot more like that in We the Parasites.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.