The road to medical breakthroughs rarely involves one solitary figure working in isolation. Instead, the processes that save lives are often the result of collaborative efforts — and the story of how a cure for tuberculosis was discovered is especially emblematic of this quality. It’s the old adage about something being a marathon rather than a sprint — only in this case, the marathon involves the efforts of dozens of people and lasts for decades.

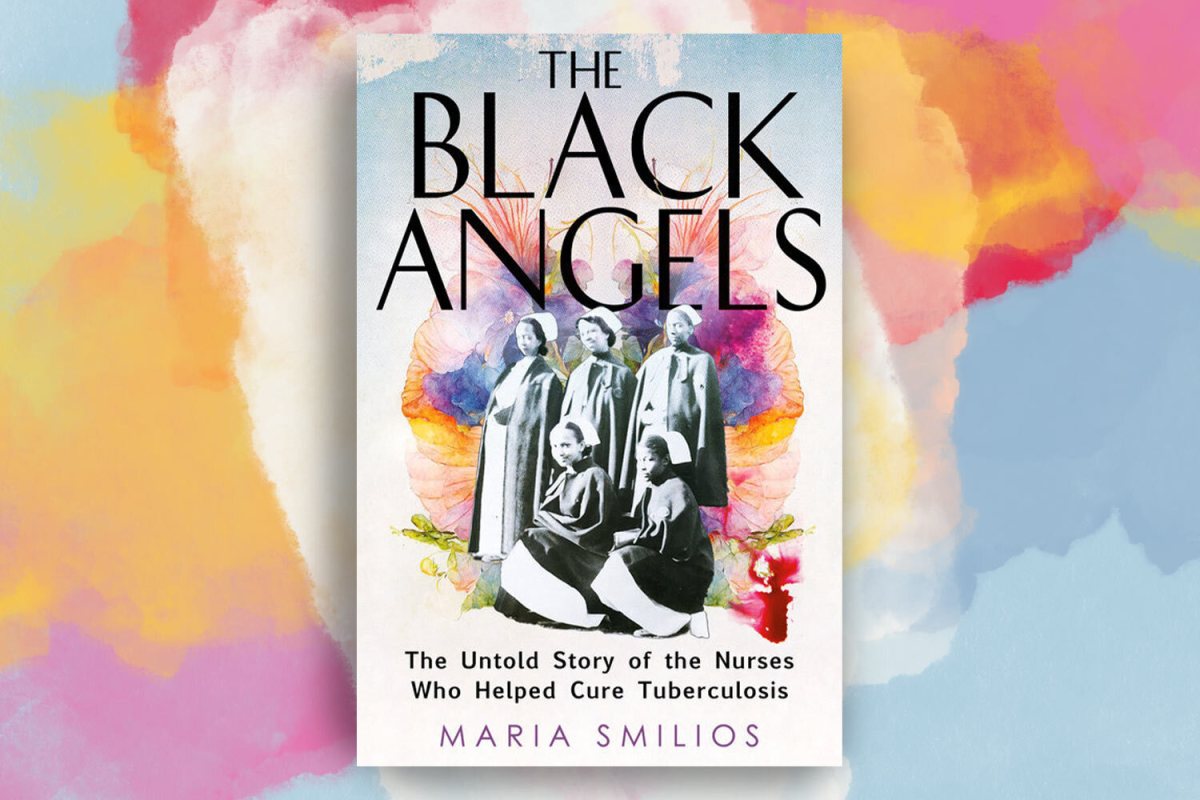

Maria Smilios’s new book The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis tells the story of the cure for tuberculosis through the work of a group of Black nurses working at Sea View Hospital in Staten Island in the first half of the 20th century. The book takes its title from the name given to these women, whose tireless work and meticulously-kept records on the chronic tuberculosis patients in their care led to a crucial expansion of how medical professionals understood the disease.

InsideHook spoke with Smilios about the genesis of her book, the parallels between the tuberculosis pandemic and the present moment, and the unexpected appearance of George Orwell in her narrative.

InsideHook: You talk a little at the start of The Black Angels about how you first learned about this period of history and the work these nurses did on Staten Island. How did you find your way into this piece of history?

Maria Smilios: I had been working as a science editor at Springer, and I was working on a book on lung diseases. I came across a line that said the cure for tuberculosis was found at Sea View Hospital in Staten Island. I love New York history. I love anything about abandoned hospitals and disease, and so I began googling, and up came this article about the cure and Sea View. Next to that was another article about a woman named Virginia Allen, who was 86. She belonged to a group of African American nurses called the Black Angels. That piqued my curiosity even more than the article about the cure and Sea View.

I began to google her and nothing came up. Eventually I found her. Well, I, I learned about her when I called the Staten Island Museum, and they told me that she would be doing a presentation the following weekend on the Black Angels for their grand reopening. So I took the ferry to Staten Island, and I met her and we began talking. Eventually she invited me to her home. She lives in the now-restored nurses’ residence at Sea View Hospital, surrounded by all of the old buildings, which are hollowed out now. She began telling me the story in snippets, and then she asked me if I could actually tell the story. That is how it began.

One of the things that really struck me about the book is how you focus a lot on a couple of the nurses and doctors who were working at Sea View — but you also give these very detailed accounts of some of the patients who were there being treated for tuberculosis. Where did some of that information come from?

I was fortunate that Dr. Edward Robitzek’s son is still alive, and he has his father’s archives. In those archives were Dr. Robitzek’s trial records on the isoniazid trials that were held at Sea View, which were the first trials of isoniazid to see if it would combat tuberculosis. There were names for all of the patients, so I tracked them down, and thankfully, two of them were still alive — Mamie Daniels and Milagros Delfaz. They were able to tell me their stories about getting sick and ending up at Sea View and almost dying and how they were fortunate to be selected as part of the 92 initial patients who would be part of those trials. So that’s how I was able to track them down, and those stories of the trial patients are all firsthand testimony.

One patient — Lena Meller — had passed away, but her family saved these letters she wrote to her daughter, so I was able to tell her story through those letters. The other ones came from newspaper articles; Hilda Ali and the other women were written about extensively in newspapers.

In The Black Angels, you make a very strong case for medical breakthroughs not being the work of a solitary genius, but instead that it takes much more of a collaborative effort. Without giving too much away, you write about how Dr. Robitzek ultimately concluded that the solution for tuberculosis had to involve a bunch of different things. There’s also the fact that the nurses at the heart of your book wrote incredibly detailed records that were critical to finding a solution for this disease. Was that something that you had a sense of going in, or did that emerged as you were doing the research?

I think it’s a little bit of both. It’s kind of like writing. People think writers write books in a vacuum. They don’t, and it takes a whole team of people to put a book together. It’s the same thing with medicine. There are people working in labs — for example, the scientists at Hoffman LaRoche like Herbert Fox. He was working with the molecules, but then he sent them up to be tested in their labs. Once that happened, more and more people got involved.

I think when it comes to nursing specifically, nurses are the backbone of the healthcare system, and we tend to forget that. We saw that a lot in COVID. The frontline workers are the people who have to take care of what’s going, you know what I mean? They become the spokespeople for the people in the back, and so while I did know that going in, I think the extensive network of what it takes to get a drug from the initial concept to the mouth of a patient was illuminating to me.

I spoke to so many epidemiologists and virologists and people who actually manufacture compound drugs, and it is an extensive network of people from that initial idea to the drug becoming a reality to it going to patients to then becoming mainstream.

Were you working on this before the pandemic? And if so, did writing about tuberculosis during a pandemic have any bearing on how the final project was shaped?

Yes and no. I am not sure if the advent of COVID changed my approach to the book as much as it enhanced the health disparities — the failing and overcrowded municipal hospitals, the patient populations comprised of immigrants and the poor, inequality in labor (especially with brown and Black women) and, of course, living with a fatal disease. I can honestly say COVID gave me a palpable sense of what it was like to live with a deadly airborne virus.

Like tuberculosis, COVID began to haunt us, make us anxious and stir our most potent fears. And so from that respect, it enhanced what was already there. Health inequity in America has always existed, but for the most part, it remains hidden unless you are living it. COVID pulled back the curtain and exposed the reality of a healthcare system that has been long broken and one that’s designed to care for some but not others. And one kept together largely by underpaid brown and Black nurses, and so I think once you live through this, then you say, whoa, we are all affected by this. It’s no longer “I can afford healthcare, so that’s not my problem.” It’s like, “Whoa, we are all in this together all the time.”

Efforts in recent years to develop a vaccine for COVID-19 have put questions of patents on medication back into the spotlight — and, more broadly, the questions of what role the profit motive should play in this kind of research. When researching this book, was that another area where you found a lot of parallels between the past and present?

I’m glad you asked that question because right now, there is a tuberculosis drug, Bedaquiline, that is manufactured by Johnson and Johnson, for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis, which is rampant in TB-heavy countries. Tuberculosis — people don’t know this — still kills 1.6 million people a year and sickens 10.6 million, predominantly in 30 countries.

The patent expired on July 25th, so Johnson and Johnson took out a second patent — and that enables them to gatekeep the drug and give it to people they want to give it to and also raise the price. The first patent expired, and there are still 11 countries that are under the second patent. The drug is very expensive and tuberculosis is rampant.

So to answer the first question of what you asked me, that story of the fact the drug couldn’t be patented was extraordinary, and it spoke so much to the greed of companies. That was part of the race for the cure. It was going to bring great glory and millions and millions and millions of dollars because tuberculosis had been around since the time of the ancient Egyptians. It reaches way, way back into history.

People found out we couldn’t patent this, that nobody could make money off of it; since then, isoniazid has saved tens of millions of lives. I think now when we look at what’s happened with the greed of drug companies and them holding drugs back — not just this TB drug, which is kind of ironic right now, but drugs in general — making it unaffordable for a lot of people. Some people have the money and can get the drug, other people can’t, and this is across the board from diabetes to cancer medications.

It was definitely eye-opening to see this thing that I associate with the 21st century has really been a going concern for much, much longer, and it seems to have been as troubling then as it was now.

Were you aware going into the project that tuberculosis remains such a problem for large portions of the world?

I did not know the extent of the problem going into the book. I knew my grandfather had tuberculosis. He immigrated from Greece, and so I knew a lot of people who had come over as immigrants, the grandparents or fathers of friends of mine had tuberculosis. So it wasn’t something that was really foreign to me.

In the United States, I think we only had like 8,000 or 9,000 multi-resistant TB cases last year. I’m not a 100% sure on that, but that’s really low when you’re looking at countries that have millions of people being affected by this. It was startling to me — not only the myths surrounding the disease, but that it is still the number one global infectious disease killer in the world. That is a really staggering thing to kind of wrap your mind around: that in 2023, this ancient disease is still doing that kind of damage.

Exploring the Secret History of Wolves

Erica Berry’s new book “Wolfish” takes a unique look at the relationship between humans and wolvesIn light of public health debates around COVID-19, one of the really shocking things you wrote about was the way that the nurses’ supervisor at Sea View was violently opposed to the idea of the nurses wearing masks and gloves. Reading that part was like the moment in the horror movie where someone goes down a dark hallway, and you want to shout, “No! Don’t go in there!” at the screen.

That was the prevailing ideology at the time, and then Dr. Jay Arthur Myers started looking at it and said, “Wait a second, the prevalence of tuberculosis among healthcare workers, particularly nurses who are working in these sanatoriums with this patient population — they are getting sick at a significantly higher rate, and so what can we do to protect them? Clearly just hand washing is not working. How about masking?”

That’s when this whole masking debate really started, sometime in the early to mid 1930s with these articles coming out, but it did not catch on. People were still resistant to it and believed in this old school hand washing, taking your clothes off, the mythology that the microbes stick to your clothes and you bring it home; no beards for men and no long dresses for women. If you do that, then you will stay safe. The supervisor ascribed to that because it was how she’d been trained, and she had come over from Willard Parker hospital, which was the most prestigious infectious disease hospital in the city. Working with smallpox, working with all sorts of infectious diseases, it worked for her. She didn’t get sick, and so that was one aspect.

She also looked for things to blame on the nurses because when she was hired, her job was to fill the ranks and to train and retain a staff. She liked to kind of stalk them and nag them. She harassed them in every way that other white supervisors harassed African-American nurses.

Another haunting aspect of The Black Angels was the extent to which the nurses who were working in these conditions were testing positive for tuberculosis, where the infection was kept under control. Was that something that was addressed sort of after the proper regimen of cure was determined, or was that something that a lot of them just lived with for the rest of their lives?

They lived with it. They knew they were positive. They knew. You can have latent tuberculosis and it never becomes active. It could be set off by different things later in life — if you become immunocompromised, for instance. HIV-positive people are very prone to tuberculosis. Pregnancy can set it off, and so can stress. Most of the nurses, by their first year, had tested positive, so they were very conscious of the precautions they had to take, like getting a lot of sleep. Which is ironic because how can you sleep when you’re working 14 hours a day, right?

I don’t think a lot of the nurses knew the risks of this coming into the job. It was something that was learned, like being entrenched in a place where you are just constantly breathing in the microbe, and it’s remarkable how long many of them lived. Edna lived to be almost 90, and so did Missouri — and Virginia is still alive and she’s 92. Robitzek lived a very long life, and his story is even more remarkable because his father had laryngeal tuberculosis in from 1923 to 1929. That’s one of the most contagious forms of tuberculosis, and when he was a child, he didn’t catch it. He had latent TB, but he never got sick, so that’s pretty remarkable. Something worked or they just had an immune system that was able to repel the bacteria and keep it in check.

Going into the book, I was not expecting George Orwell to put in a cameo appearance. When did you decide to include him in this and move outside of the hospital for that part of the narrative?

I fell in love with that story. I wanted him in the book and I had to find a way to get him in the book — and it fit beautifully with what I was discussing with the haves and have nots of streptomycin being expensive and the people who could afford the drug being able to get it. I mentioned a guy named Arthur who died because he wanted streptomycin and the hospital just didn’t have enough funds, so they started to do what we did with COVID, meting out who was going to get what. Orwell became this perfect example of someone who had the money. He writes to Astor and he says to him, “Buy me the drug. The worst I could do is waste my money.” Sadly, he’s allergic to it and it doesn’t work for him. He starts to have these reactions to it that the nurses were starting to see at Sea View, and because there had been no long-term trials on the drug, there’s a sense of, “Oh my goodness, what is happening here?”

That’s how I was able to weave it in, but it took me a long time to find a way. I just found it so fascinating that he was trying to finish the manuscript of 1984. They said he might have very well based the demise of Winston on his own demise. This was kind of meta now in this broader moment in time, but it was also relevant in terms of who’s watching who and who can get what.

You mention in the book that there’s a mural in Staten Island dedicated to the Black Angels, and that Virginia Allen has been doing presentations on the work that she and her colleagues did. Does anything else exist that pays tribute to the work they did towards finding a cure for tuberculosis?

Governor Pataki had given a proclamation from the city of New York and he declared March — I think it was the 15th — Black Angels Day a few years ago. There is a museum that is falling apart at Sea View that was named after one of the first African-American supervisors, Stiversa Bethel. But because nobody has watched it, it’s fallen into disrepair. That sign fell down and now it’s just referred to as the Sea View Museum, but it officially had been inaugurated by Pataki and the government at the time. They had a dedication ceremony and Miss Stiversa Bethel was there, and they unveiled a plaque.

That is the only thing that I know of, aside from Virginia telling the story in this small community on Staten Island. Other than that, there’s nothing. I hope now there will be lots of things to mark their legacy, but as of now, no.

Was there anything you learned during the course of researching the book that you found fascinating but which didn’t quite fit into the overall narrative of the book?

Oh my gosh, there were so many things. Gerhard Domagk, who discovered Prontosil, his story is remarkable. He worked for Bayer. Bayer started working with the Third Reich, and he was horrified. He won the Nobel Prize for Prontosil and was put in jail by Hitler because of it and could not receive it; eventually he received it many years later. So that was one story.

There were lots of these fascinating ancillary stories about the pseudoscience that I could only fit in tiny paragraphs — like people who had tried to get cured in places in far-flung villages. There was one place, I think it was in London, where a male doctor would rub women’s breasts and say he was rubbing the disease out of it. All of these quacky, quirky, charlatan-type things.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.