More and more vehicles manufactured today are connected to the internet. That’s a good thing, right? In some ways, it is — internet connections can make it easier to roll out software updates and send emergency services to a vehicle’s location after an accident. But as internet connections become a more regular feature, some drivers are learning about an unexpected downside: Insurance companies might have access to very granular data about how they drive. And that, in turn, can lead to them paying significantly more for insurance.

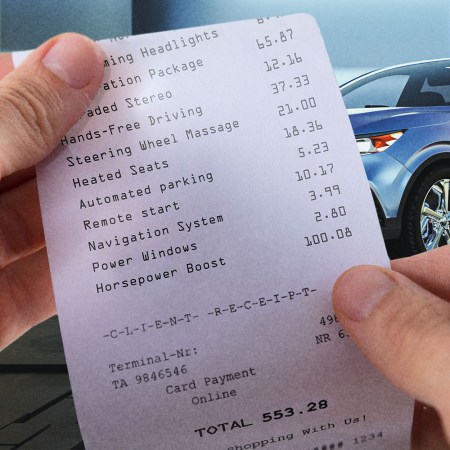

That’s the gist of a blockbuster New York Times report by Kashmir Hill — a reporter who wrote the book on technology and privacy. Turns out some automakers send their data to LexisNexis, which in turn sells it to insurance companies. This can mean that instances of hard braking could be tracked and recorded — and eventually lead to higher insurance when it comes time to renew coverage.

As Hill points out, some automakers are more clear about sharing drivers’ data with third parties than others. Others are not; Hill cited her own experience with the Smart Driver program — which “provides driving insights on how you can become a smarter, safer driver” — as one example. “I have a G.M. car, a Chevrolet,” she wrote. “I went through the enrollment process for Smart Driver; there was no warning or prominent disclosure that any third party would get access to my driving data.”

In 2024, This Millennial-Favorite Collector Car Will Finally Be Legal in the US

Randy Nonnenberg of Bring a Trailer discusses the hottest vehicle heading to the country after the end of its 25-year banThe issues of privacy and what drivers believe they are consenting to is one big theme of the Times report, but there’s an even broader question looming above it all as well. Namely, how the industry, as a whole, conveys this to the drivers who might be affected. Hill notes that lawmakers on the state and federal level are concerned about this — and that drivers themselves have some resources to draw upon. But in an era of labyrinthine terms of service documents and lengthy chains of third-party services, spelling out exactly what companies have access to what data is surprisingly complicated.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.