Performers in Yorgos Lanthimos movies generally act as if they’ve never encountered an actual human person firsthand, just had one described to them by their director, possibly in a voice dripping with sarcasm. The dialogue in Lanthimos movies is blunt in a way that strips away social nuance — characters reveal harsh opinions, express troubling desires, and discuss bodily functions with oblivious candor — and line readings are accordingly flat, robotic and expressionless. His plots often feature characters who have committed to cruel, arbitrary premises, whether about a tyrannical father who forbids his children to leave the house and teaches them incorrect definitions of any word suggestive of an outside world, as in his breakthrough Dogtooth, or a dystopian future in which all citizens must enter into a romantic partnership or be turned into the animal of their choosing, as in The Lobster. His visual style leans on wide-angle lenses that uglify faces and distort interiors, giving the image a fisheye bulge that recalls a slide under a microscope, or an ant under a magnifying glass.

The implication of Lanthimos’s approach is that the human race is comprised largely of ponderous dullards, afflicted by a pedantic adherence to whatever set of rules is imposed on them. People behave without feeling or understanding, simply submitting to authority — often to their detriment, as in shocking and graphic instances of self-mutilation that pock his films. Such moments of abrupt violence (characters hitting themselves with heavy objects, or slamming their heads onto hard surfaces) recur throughout his films, inevitably filmed in dispassionate wide shots; so to do dance interludes with sexualized but aesthetically awkward modern choreography. These motifs are consistent across his films, regardless of their dramatic function or the surrounding subject matter. One fascinating thing about Lanthimos is that he applies a uniform approach to wildly different stories, for which his style may or may not be a particularly good fit (beyond its darkly funny surface pleasures). The Killing of a Sacred Deer, a modern-day Greek myth about human sacrifice, is a perfectly legible allegory for the cost of prosperity, but Lanthimos ignores its uniquely and pungently American setting to flatten it into purely theoretical parable. In The Favourite, he gets cheeky with an already perfectly cynical palace-intrigue melodrama — though admittedly his chilly distance makes a great echo chamber for ferocious performances by Olivia Colman, Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone.

In Poor Things, Stone plays Bella, an adult human body into which an undeveloped brain has been implanted — an artificial life form, then, who eventually learns to become human through comically awkward imitation of the society whose customs she metabolizes and, naively but also wisely, comes to question. A blank slate onto which ideas about morality, sexuality, politics, science, philosophy, manners are inscribed in turn, she is also an ideal vessel into which Lanthimos can pour his usual preoccupations.

Poor Things is a Frankenstein story, full of gods and monsters. Victorian anatomist Godwin (Willem Dafoe) has a scarred face and a gastric bag — everything but the neck bolts, ravages of his early life as the subject of his own father’s biological experiments. As an adult, “God” (as everyone who knows Godwin calls him) creates new life in his London manse; hybrid creatures, such as a half-bird-half-dog, wander the back garden like it’s Dr. Moreau’s island.

In this steampunk Eden, Bella stands out as God’s most extraordinary creation. Stone in the film’s early scenes moves out of joint, with stiff limbs and uncoordinated extremities; a creature of impulse, Bella takes great pleasure in the squishy textures of God’s laboratory — where she giggles as she stabs a cadaver repeatedly in the face — and is prone to plate-smashing tantrums when God permits her from leaving his garden.

Bella, as it transpires, is the reanimated body of a pregnant young woman who had committed suicide, into whose head God had inserted the brain of her own fetus. With her adult physique and untouched consciousness, Bella is an inverse to the fantasies of 21st-century transhumanists, who dream of downloading their consciousness into a younger meatsack, perhaps a clone of themselves. In Poor Things it’s the human mind, not the body, that gets a much-needed reset.

Bella matures rapidly — she discovers sex, which she takes to with an adolescent’s giddy emerging awareness of an adult body with previously unfamiliar functions. Her newfound enthusiasm for “furious jumping,” as she calls it, inspires God to hide her away from a world she isn’t ready for, or which isn’t ready for her — like another of cinema’s recent domestic playthings, Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla Presley, Bella on multiple occasions finds herself locked inside a mansion, in a synecdoche for a previous era’s ethos of domestic confinement.

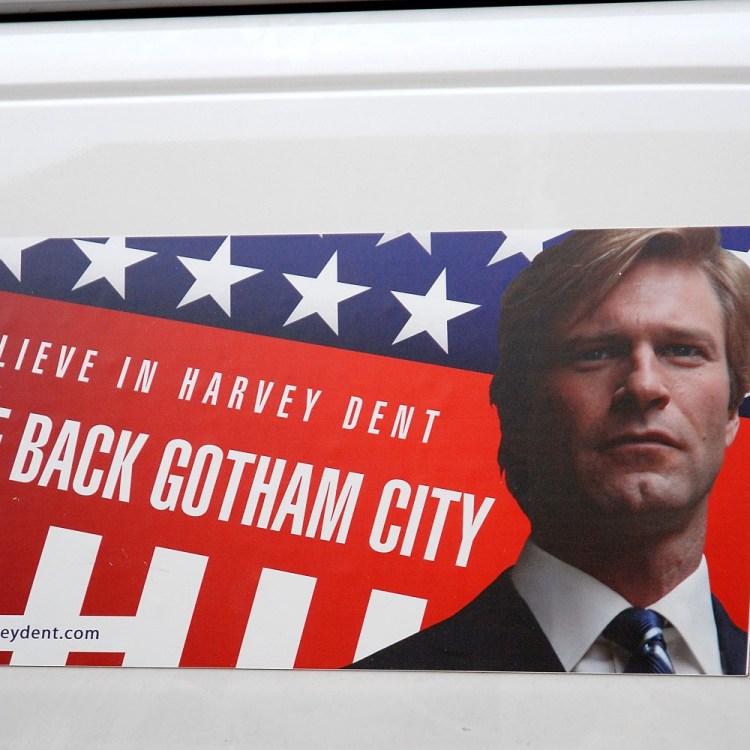

Bella must surely be “quite a woman to warrant such binding,” realizes the lawyer Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo, seizing on the historical mishmash of Shona Heath and James Price’s production design and assuming a silly, totally unjustified transatlantic pastiche accent for the sheer fun of it). Especially given the setting in 19th-century London, a time and place associated with both the stirrings of first-wave feminism and iconic prudery, Bella represents the link between sexual pleasure and free will. This opens her up to being used by cads like Wedderburn, but the benevolent God lets Bella run off with him anyway; he knows she can’t be controlled, and has faith that she’ll gain wisdom with experience. (The cuddly and bohemian Dafoe is an ideal actor for this role, essentially a personification of the Spinozan conception of God as a cool uncle.)

Bella and Wedderburn embark on a Grand Tour of Europe, rendered in Trapper-Keeper skies of lurid blue with wispy pink clouds; city blocks are jumbled together with the teetering density of an Escher drawing, embellished with trams and other fanciful traces of the Industrial Revolution’s unrealized utopian potential. The film’s visuals are compressed and oversaturated; the world that Bella discovers is full of “sugar and violence,” and she ingests it at 1.5x speed.

Wedderburn tries to teach Bella about pleasure: he orders oysters and indulges in much furious jumping, though Bella soon learns that even notorious rakes are not immune to the refractory period. Indeed, because of Bella’s inextinguishable appetites, her hunger for pleasure and knowledge — her lust for life — she is constantly banging her head against the limits enforced by the purportedly older and wiser.

Emma Stone Delivered a Perfect Rendition of Steve Martin’s “Planes, Trains & Automobiles” Monologue

And Steve Martin appeared to like itWith the brute logic typical of a Lanthimos character, Bella questions why her needs, physical and otherwise, must go unfilled. Why not spit out your dinner if you don’t like how it tastes? Why not slap the baby if it’s crying too loud? There are reasons, in some cases — we live in a society, but in Poor Things the people who live by society’s rules appear notably incapable of understanding or articulating them. What kind of society is that? Instead of explanations, Bella gets limitations: when she’s too candid with her dinner conversation, upsetting the other diners, Wedderburn restricts her to three dull, polite, anodyne phrases.

The constraints on her vocabulary gall especially, given that Bella’s evolving facility for speech, her ability to express herself and describe the world, is key to her character. In parallel to her sentimental education, she progresses from grunts; to present-tense sequences of nouns, like Koko the gorilla; to a child’s self-conscious malaprop-laden loquaciousness; to a notably cultivated syntax. Tony McNamara’s script, adapted from Alasdair Gray’s novel, is dexterous in tracking Bella’s development through her ever-improving grammar, but it’s down to Stone to imbue Bella with an essence. Over the course of two hours and 20 minutes, Stone has to change her vocal modulation and physical carriage beyond all recognition while still maintaining, for lack of a better word, her soul, in the same way that a baby you coo over necessarily contains the seed of the adult it will eventually become.

As Bella’s journey takes her by ship across the Mediterranean, and to the streets of Paris, watching her “questing self” in action eventually feels like watching a young woman speedrun all of college. Bella parts tearfully and sensitively from her first boyfriend (Ramy Youssef as God’s assistant), she gets too hung up on the first fuckboy to give her an orgasm, she overindulges on alcohol, she gets inspired by music when she hears a fado singer in Lisbon, she gets an impulsive tattoo, she starts reading theory, she makes her first nonwhite friends, she becomes horrified at the revelation of her relative privilege and the realities of suffering in the developing world and tries to solve it all by herself, she dabbles in sex work, she explores her bisexuality, she becomes a socialist, and ultimately she even explores the root of the depression that plagued her, or her mother, before the events of the film. She learns, in short, to be a person in the world. Throughout, Bella is inspired by the wisdom of the people she meets — a well-read cynic played by Jerrod Carmichael; Kathryn Hunter’s worldly Parisian brothel-keeper — and takes on elements of their character, even if they are, finally, compromised by their past experiences in the way that Bella, with her fresh and resilient Silly Putty brain, is not.

Previous Lanthimos films have sometimes been optimistic, at least cautiously, about people’s capacity for growth: in Dogtooth, one of the dictator-patriarch’s daughters, emboldened by samizdat videotapes, begins to plot her escape; The Lobster ends on a moment of aching suspense as Colin Farrell’s character questions the necessity of an act demanded of him. These examples stand out amid a filmography populated by banal and unimaginative plodders content to just follow orders. But a student of life, Bella surpasses them both — she’s a prodigy, Lanthimos’s star pupil, and he tells her story with real gusto. After a film spent snacking on the fruits of the tree of knowledge, she is even permitted back into the garden. Her progression from automaton to God-like being — with a moral sense, curiosity and sliver of bemusement — is riotously entertaining. The God’s-eye-view from which Lanthimos usually looks upon his characters is, finally, hers.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.