Much has been made about Adam Driver’s casting as Enzo Ferrari in the new Michael Mann-directed biopic, Ferrari, which was released on Christmas Day. Is the 40-year-old actor heavyset enough? Conniving enough? Italian enough?

Aside from the arguable physical resemblance (or lack thereof) to the larger-than-life founder of Ferrari, Driver’s portrayal of “Il Commendatore” slips into a bigger mise en scène that includes Penelope Cruz’s smoldering depiction of Enzo’s wife Laura, Shailene Woodley’s convincing portrayal of his mistress Lina, and a smattering of real-life racers including Patrick Dempsey, Derek Hill, Marino Franchitti and Samuel Hubinette who blur the lines between actor and driver.

While I’ll leave critical analysis of the cast’s capabilities to the Screen Actors Guild and the Oscars committee, I can confidently share that the film’s mechanical fidelity — the vehicles, the race sequences, the driving shots — were exceptional. To watch Ferrari on the big screen is to immerse yourself in a period of motorsports history that comes alive in balletic beauty. If you enjoyed the 1991 Brock Yates-penned Enzo Ferrari biography the film is based on, you’ll revel in the period details and gut-wrenching action sequences that offer a palpable complement to the personal dramas that defined one of the most turbulent periods in Enzo’s troubled but ultimately triumphant life.

The automotive action falls under the purview of Robert Nagle, the film’s stunt coordinator, whose previous credits in the stunt-driving department include such automotive showcases as Ford v Ferrari, the first two John Wick movies and a good chunk of the Fast and Furious franchise. For Ferrari, he orchestrated every driving sequence to ensure that Mann’s vision was brought to life; that the vehicles’ on-screen dynamics are not only exciting, but believable; and that the stunts are safe for the cast and crew. No small feat, given the film’s ambitious scope.

Nagle comes from the unusual place of being both a stunt coordinator and a driver, having drag raced, road raced, and studied race car engineering at Chaffey College. Like many a gearhead cinephile, Nagle credits 1998’s Ronin among his top car movie inspirations. “I’ve always loved the chase scene in Ronin because it’s so realistic,” Nagle says. “The way they configured the cars to put the actors in the middle of the action really sold it to the audience, and [you] really felt the speed and how precarious it could be. I’ve always strived to get that kind of realism.”

Shooting a period racing film set in 1957 Italy presented an entirely different creative challenge. Unlike contemporary cars, which envelope the driver in a greenhouse of steel and glass that can easily cloak a stunt driver’s face, mid-century race cars featured open-air cockpits that make it nearly impossible to mask their identity; thus, real drivers were cast in the roles.

“Keeping drivers safe in these open-top cars meant hiding five-point harnesses beneath their costumes,” Nagle reveals. “It presented a whole different range of challenges I hadn’t dealt with before because most of the other cars in the past were relatively contemporary. There was a lot of planning involved to get it right.”

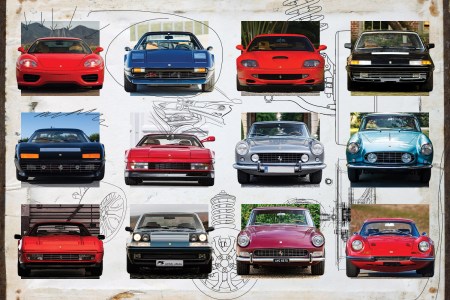

The Classic Ferrari Collector’s Guide

A decade-by-decade look at the Prancing Horse’s sports and touring cars, including underappreciated models to know and buying advice to followAnother common point of contention among enthusiast audiences are the vehicles themselves, which are often scrutinized both for their aesthetic, sculptural qualities as well as their dynamic appearance when they’re sliding through a corner or roaring down a straightaway. Are they the real deal? Recreations? Animations? For Ferrari, Mann famously avoided CGI for most of the movie’s action sequences, but because some of the cars depicted are valued into the tens of millions of dollars, one of the few original vehicles used for action shots beyond some private collector cars was Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason’s Maserati 250F racer — still a ridiculously valuable vehicle in its own right.

“We had to replicate the sports race cars like the 315s and 335s that we used in the film,” says Mann. “You couldn’t possibly use the authentic ones; we needed the cars to be safe, reliable, and very very fast.”

That meant 3D Lidar-scanning originals for the bulk of the cars used in the Mille Miglia rally scenes, some of which were sourced from Ferrari’s museum in Maranello. The reproductions were executed by Carrozzeria Campana in Modena, which built both fiberglass bodies for driving and hand-hammered aluminum bodies for crash scenes in order to accurately depict the crumpling of metal. Those manufactured body panels were fastened onto Caterham chassis powered by supercharged, 340-horsepower four-cylinder engines.

“They’re very close in wheelbase and track width, so it didn’t take much modification,” Nagle says. “At the end of the day, I think they only weighed 1,800 pounds, so they handled well and were incredibly fast. They did everything we asked.”

As for the rapport between stunt director and actual director, Nagle estimates the two have collaborated on “a half dozen films,” enabling a generous amount of shorthand on this latest project. Also elevating their communication skills is the fact that both have a background in competitive racing, with Mann having raced in the Ferrari Challenge Series.

“He loves it and has a very good aptitude for it. That’s half the battle right there,” Nagle says. “There are moments when he’ll ask for something and I’ll have to say, ‘Michael, the car is just not going to do that,’ or ‘we’re already at the limit.’ There’s a back-and-forth conversation with certain instances like that. But to Michael’s credit, he’s also well-versed with race cars so he gets it pretty quickly as to what are capabilities and limits are.”

Nagle was able to drive the cars himself in some scenes, delivering the level of speed and performance required to sell audiences on the viscerality of racing in the 1950s when the consequences of crashes all too often led to serious injury or death. The fact that actor-drivers like Patrick Dempsey claim years of racing experience, including competing in the grueling 24 Hours of Le Mans for Porsche, didn’t hurt either.

“He did pretty much all of his own driving,” Nagle says. “He did a great job and is a fantastic driver, with the added bonus that since he’s an actor, he already understands how to play to camera.”

Meanwhile, over Nagle’s long career, which has also included work on such automotive standouts as Drive and Baby Driver, the stunt maestro has not only learned how to play to camera, but to the car enthusiast and the layperson as well. You may not be able to discern every little detail that he’s checked off his long list in an attempt to elevate the stunts in Ferrari to a level worthy of Enzo, but you’ll certainly feel them when the rubber meets the road.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.