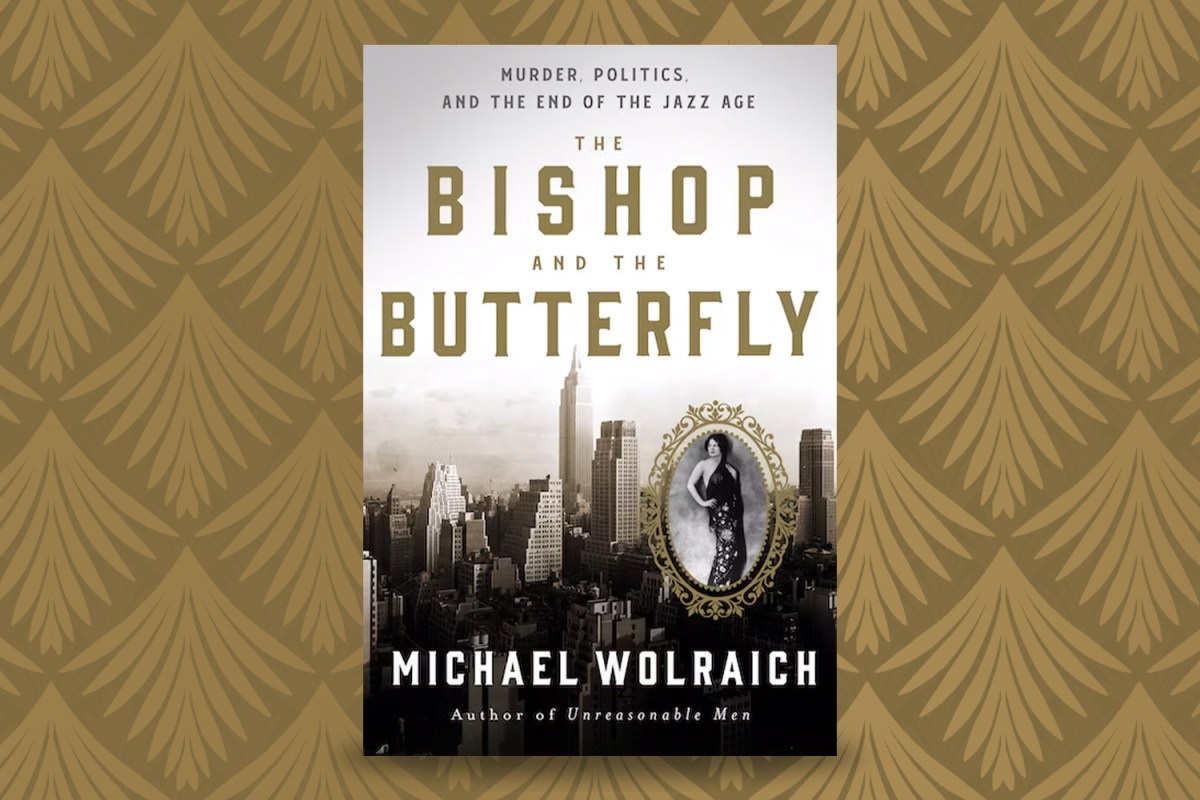

Can a murder case rewrite the political landscape of a city — and, potentially, a nation? In his new book The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age, Michael Wolraich makes the emphatic case that one can. This work of nonfiction begins with the 1931 killing of a woman named Vivian Gordon, whose own life contained secrets within secrets.

Gordon’s murder shocked the city, and prompted a series of investigations led by the well-respected Judge Samuel Seabury. What Seabury’s commissions unearthed led to a sea change in urban politics — and had an effect on the political fortunes of New York’s governor at the time: one Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

InsideHook spoke with Wolraich about his research into this case, the unexpected ways it resonates with present-day New York City and its unlikely connection to a failed Norwegian bank heist.

InsideHook: How did you first learn about the case of Vivian Gordon’s murder?

Michael Wolraich: Gordon’s murder doesn’t seem like it’s a piece of New York history that’s quite as well known as some other sensational murders that have happened over the years. It was huge in its time. It was front-page news in all the New York papers for months — and not only the New York papers. Headlines were appearing nationally. I found reports as far away as Sydney, Australia, and Singapore. But it’s been largely forgotten since then.

The way I came about it, it’s a little embarrassing. It was Wikipedia. When I’m brainstorming for topics to write about, one thing I sometimes like to do, I call it wiki-surfing, where I do shallow dives into various topics and just click links and see where I end up. I was kind of toying around with FDR. His presidency is very well known, but not so much his time as governor.

I was playing around with what was going on while he was governor and the anti-corruption investigations that he initiated. On this Wikipedia page, there was a reference to a murder of Vivian Gordon that was related to those. I wondered, “Who’s Vivian Gordon?”

I clicked on the link, and there’s no page. Then my curiosity was piqued. I started doing some more serious research and found out that her murder was a fascinating story, and even more significantly, actually played a significant role in those anti-corruption investigations, which had a huge impact on New York City’s history.

From having watched Gangs of New York, and from having read the book Low Life, I’d always thought of Tammany Hall as very much being a 19th-century institution. I don’t think I had realized just how significantly they had a presence in the city, at least in the first half of the 20th century. How much of this history did you know already? And how much of it surprised you as well?

From my previous work, I certainly knew a fair amount about Tammany Hall and New York State politics. My previous book was about Theodore Roosevelt and his battle and that of some of his Republican allies against the political machines of their era, which was the early 1900s. So, it was a bit before that time. But Theodore Roosevelt certainly made his name by taking on Tammany Hall and the political machines in various ways. I knew a bit about that, but I didn’t know as much about this period. And I was a bit surprised by FDR’s complicated relationship with Tammany Hall.

I knew that he had been an anti-Tammany Hall guy at one point, that he’d campaigned against Tammany Hall. That had been true when he first embarked on politics and was in the New York State Assembly. But he quickly abandoned that approach because he found out that as a Democrat, it would be very difficult for him to progress in politics in New York without the support of Tammany Hall. In this respect, he differed from his cousin, Theodore, who was a Republican and so could continue to bash Tammany Hall throughout his career.

FDR made peace with the Tammany boss and they worked together to advance the Democratic Party in New York and FDR’s career in particular. When you reached the 1920s and early 1930s, FDR found himself in a difficult position. On one hand, he had long had this alliance with Tammany Hall. He needed their support to win the Democratic presidential nomination and help him win New York State in the general election. On the other hand, Tammany Hall had reverted back to its more corrupt origins and had become a political embarrassment for FDR. Threading that needle proved a very difficult challenge for him leading up to his presidential campaign.

In The Bishop and the Butterfly, you cite a lot of contemporary news reports, as well as comments made by associates of Samuel Seabury and FDR that were made after the fact. What was the process like as far as going into the archives for this? Was a lot of it readily available?

It was a mix. We refer to Seabury as having a single investigation, but technically there were three separate investigations. The second and the third were authorized by New York State and the transcripts for those hearings exist in the municipal archives. Seabury published public reports about his findings. There is also a published report for the first investigation, which is the one that I was focused most on because that’s the one that addressed Vivian Gordon. It was the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court.

For those hearings, Seabury destroyed the transcripts to avoid embarrassing the people who were mentioned in them. I searched high and low for those transcripts and only belatedly realized that they’d been destroyed. So those were not available.

There were also court records, but the Bronx County courthouse archive is in a sorry state. I had a lot of difficulty finding anything related to Vivian Gordon’s murder case there. For her case, the newspapers were invaluable. The New York papers, especially the Daily News, which was the nation’s first tabloid and really focused on crime and loved sexy stories like this, they were all over it, and they actually had a crack team of crime reporters. I write in the book about one of them, Grace Robinson, who was a very impressive reporter. I was able to get a lot of detail about the case just from her reporting and from other newspaper sources.

You mentioned you’ve written a book about Theodore Roosevelt as well. As you dug into writing and researching this one, did you end up finding any sort of unexpected connections between it and your previous work as you went deeper into the history?

One in particular. Samuel Seabury, who was selected by FDR to lead these anti-corruption investigations in Tammany Hall, had previously been a judge and advanced up to the Court of Appeals, which is the highest court in New York State. In 1916, he was encouraged by Theodore Roosevelt to run for governor.

Now, Theodore Roosevelt, as we mentioned, had been a Republican, but in 1912 had split with the Republican Party, and launched a new party called the Progressive Party. It’s popularly remembered as the Bull Moose Party, in honor of a phrase he used to say, that he feels “as strong as a bull moose.” In Seabury, he saw an anti-Tammany Hall crusader. They were both blue-blooded New Yorkers. They were both progressive. They had a lot of similarities.

Roosevelt encouraged him to run for governor and promised to support him. Seabury was torn, but ultimately resigned from the court and pursued his ambition to run for governor. But then Roosevelt turned on him, and decided, after all, to throw his support to the Republican candidate. And without his support, Seabury didn’t have much chance and lost the governor’s election. As I describe in the book, Seabury went off to Theodore Roosevelt’s home in Long Island and confronted him and called him a “blatherskite.”

I’m sure it was deeply damning at the time, but now “blatherskite” just sounds incredibly strange.

It probably sounded that way back in the day, too. Seabury was very intellectual, very imperious, very clean-cut. He didn’t curse or anything like that. Gangsters would not be calling each other blatherskites. It means somebody who blathers on, prattles on.

One of the sort of minor figures in this case is someone known as Chowderhead Cohen, and there’s a paragraph where you list the clients represented by one defense lawyer who have names that feel like something out of Guys and Dolls, but are actually real people. Were there any other stranger-than-fiction moments as you went into the archives for this?

I wrote about an attempted bank heist in Norway that had been bankrolled by Vivian Gordon. She had been connected with a few ex-cons from Sing Sing. One of them was friends with another Sing Sing ex-con who was Norwegian and returned to Oslo and invited them to help him do an inside job at a bank there.

This guy Vivian Gordon knew as Harry Saunders, and two other safecrackers, they got money from Gordon, booked passage to Norway, met up with the Norwegian guy and rented a cottage outside of Oslo along the fjord. They came up with a cover story about how they were filming a movie: one of them was a Hollywood mogul, one of them was a wealthy doctor and one of them was a railroad heir.

Whenever the neighbors would come by to see what they were doing, they had some machine with wires coming out of it that they would show to them. The reporting by the Norwegian papers is hilarious. It’s talking about how the Norwegians were surprised by how slovenly they dressed, but still managed to go out with all the young women in the area while they were plotting this bank heist — which they never actually pulled off.

I was not expecting this whole tale of corruption and murder in New York to take a detour to Norway, but I was very glad that it did.

You bring up the fact that in one of these cases, the judge was Roy Cohn’s father. Were there any other places where you noticed little bits and pieces where this almost century-old case resonated with the current state of New York?

Yeah, I think there are a lot of timeless elements. One thing I write about are the abuses by the unaccountable New York City police. Those obviously came to the fore during the Black Lives Matter protests. In this book, I was writing about their abuses of women — particularly accused prostitutes, many of whom were innocent, but were framed by vice cops as part of their racket. So that certainly resonated.

The corruption is not what it was back then, but it certainly continues. I mean, there was a news story, I think it was last week, about superintendents in New York City public housing taking kickbacks from contractors.

And then, of course, we have a mayor who, like Jimmy Walker, dresses well and likes the nightlife. Jimmy Walker was known as the night mayor and Eric Adams calls himself the nightlife mayor — both of whom have some shady connections. So I definitely see some parallels there.

I wrote a piece for The Hill a couple weeks ago about how there was a Times article by Sarah Maslin Nir about Eric Adams’s clothing that received a lot of criticism for being superficial and for even being potentially racist by focusing on the mayor’s clothes. My piece looks at how Jimmy Walker was covered in a very similar way, and how there were actually important questions to be raised because Jimmy Walker’s lifestyle cost a lot of money. New Yorkers eventually found out how he was able to afford that. But Eric Adams, we don’t yet know.

We’re Living in the Golden Age of the Downtown NYC Memoir

New books from John Lurie and Marc Ribot are the latest entrants into a decorated canonWas it a challenge to make sure that Vivian Gordon was always present throughout the narrative, even though the amount of time that she is actually on the page isn’t as high as, say, Seabury?

Yes, I would say that the biggest challenge in writing the book was essentially to describe this history in a way that was chronological and was readable as a narrative. This is not an academic book. I write narrative nonfiction, so it was important to me to tell a story, and I’m really telling two stories.

One story is Vivian Gordon’s story and the story of her murder. The other is the story of Samuel Seabury and his investigations. I wanted to weave these two; they intersect at points and then veer off, but I wanted to weave them together throughout the book. That was a real challenge.

I wanted to get people hooked on the murder, and so I do start with the murder, but to explain why her murder was so important and why New Yorkers reacted with such outrage really depended on a lot of historical context. So I had to kind of leave that aside, go into history, and tell them about FDR and Tammany Hall and Samuel Seabury, then come back to the murder and gradually, through press reports and witness interviews, put together Vivian Gordon’s life story at the same time as I’m covering the murder investigation and the anti-corruption investigation.

I was able to because these events happened in parallel, for the most part. The last two chapters occur after the murder case is over, and by that point, Vivian Gordon was to be forgotten already. Those two chapters focus on Seabury and his confrontation with Mayor Jimmy Walker and FDR’s handling of this crisis.

Was there anything else that was particularly challenging about writing this book? Is there anything that you would like readers to know going in?

Another very challenging element for me was bringing Vivian Gordon to life. Much was written about her death, but it was very difficult to piece together her life story, and a lot of the details remained unknown. We don’t have dialogue. We don’t have a lot of details. Part of her story is based on these diaries that were recovered at her apartment and covered the last three years of her life, but there were no recorded diaries before then.

And at least later in life, she was a criminal. She preyed on these wealthy men. She could be cruel, and was not very sympathetic. So it was a challenge to pierce through the media coverage and find the details in her life that bring her out as a human being, and a human being who suffered a terrible tragedy — to turn her into somebody that readers, as they read the book, can hopefully relate to.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.