The thing about algorithms that’s both appealing and frustrating is their lack of transparency. At their best, they seemingly miraculously provide something we want — whether it’s a cute dog video or a piece of personal electronics. At their worst, they direct us to things we don’t want or are actively repulsed by — and it’s nearly impossible to figure out why.

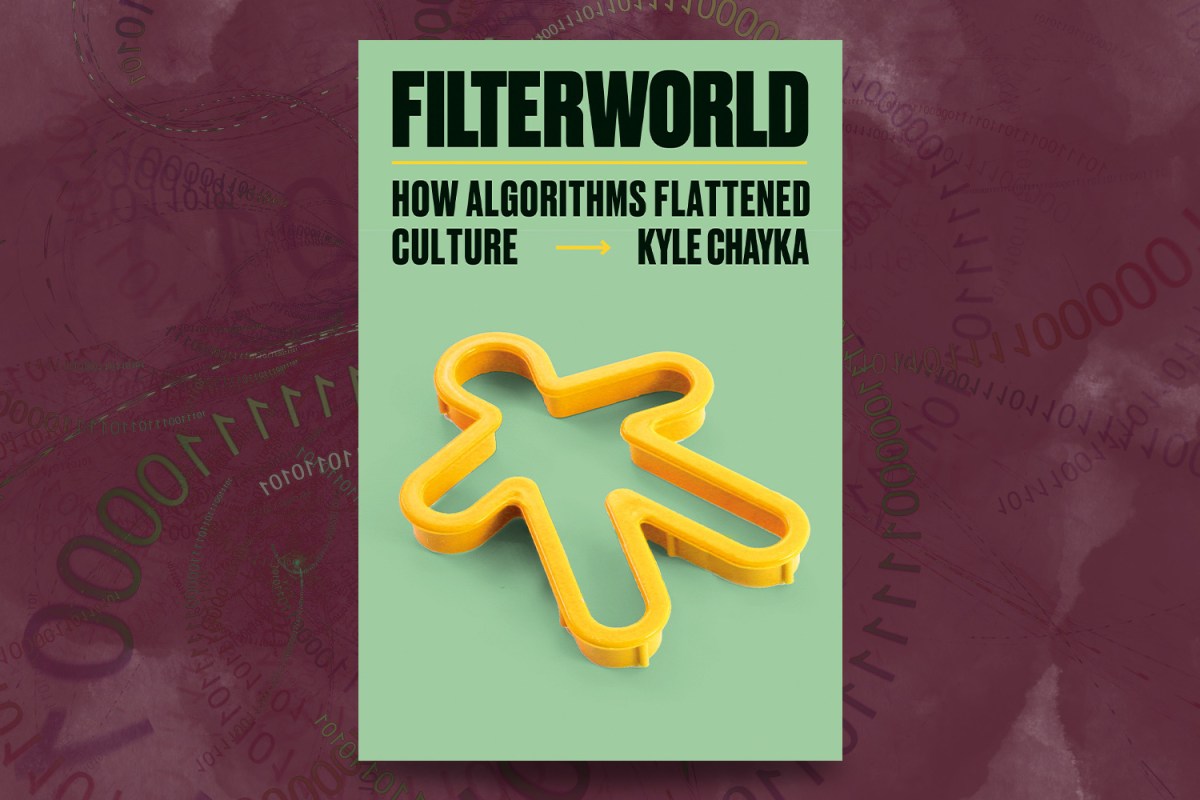

The question of how we got here, and how we might move beyond it, is at the heart of Kyle Chayka’s new book Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture. Chayka, whose previous book explored the increasing ubiquity of minimalism, also writes regularly about technology and design for The New Yorker. Filterworld is a thoughtful, comprehensive read — the sort of book that leaves you righteously angry in places and feeling unlikely surges of hope at others.

Chayka talked with InsideHook about the origins of Filterworld, its connection with his larger body of work — and how we might find our way to a place where algorithms don’t govern our lives.

InsideHook: There are a few areas, especially when you’re writing about ambient music, where I could see some thematic overlap with your first book, The Longing for Less. Did Filterworld emerge out of work that you were doing on that? Was it more of a result of the writing you’ve done for The New Yorker — or was it entirely separate from all of those things?

Kyle Chayka: I do feel like the more my career goes on, the more I know what my themes are — the Kyle Chayka pet topics. Circa 2015 and 2016, I was thinking a lot about algorithmic platforms already — or, more basically, Instagram. And I was working on the “Welcome to Airspace” essay, which mainly focused on Airbnb, but also Instagram aesthetics. I was thinking about minimalism at the same time, it being the generic style of Airbnb — and Instagram being minimalism, in a way.

So I’d say that the two books started out in my mind at the same moment, but The Longing for Less taking on minimalism specifically was much more doable for me as a person with an art history background who had not written a book before. There was a thought in my mind — “I could go for a book on this Instagram and Airbnb stuff” — but at the time I did not know how I would do that, and it took another five or six years to fully formulate that in my mind. I think what happened is that what I was observing then just kept getting worse and worse and worse, and technology became more and more all-encompassing.

It was very courteous of Spotify to release its “daylist” graphics just before the publication date of your book. That seems very serendipitous.

In so many ways right now, the algorithmic feeds tell us who we are. Spotify Wrapped does that, as does the TikTok “For You” feed. Since it seems to be so subconscious and intimate in a way, it tells you who you are. It’s almost like you shape your identity around what’s being served to you rather than shaping it around what you like as yourself.

I don’t have TikTok downloaded, but now that you mention it — when I read about TikTok’s feed and the way it monitors your reactions, it starts to sound like the implicit bias tests that people study to monitor different types of racism.

It’s like a psychological evaluation at a subconscious level because it’s measuring your reactions faster than you are conscious of them. I am on TikTok; I got on in part because it’s my job and in part because I was so bored in 2020 and 2021. And on Instagram or Twitter the signal, the data that you output is what you like, or what you retweet or comment on. And that’s a very intentional signal — “I am choosing to do this,” I push the button, blah blah blah.

Whereas on TikTok, the signal is the microseconds that you’re paying attention to a thing and how fast you swipe upward. It’s much more passive, it’s much more like reading — reading what you are and how you are reacting before you even know your own reaction. I feel like that’s why the feed is so attuned to you — but also that’s like a nightmare. I don’t know if that’s what we want in our lives.

One of the things you brought up in Filterworld was the effect of BookTok on publishing and favoring certain literary aesthetics. That made me think back to a couple of years ago when Kara Walker’s sphinx sculpture was at the Williamsburg waterfront. I can remember reading an argument that one of the reasons for its popularity was from people taking selfies in front of it — which then got me wondering about other forms of art where algorithmic popularity have led to certain works succeeding. When did the trickle-down effect of this start to come into play for you?

I got on Instagram in early 2012. I think that was early on. And its mainstreaming process wasn’t super-universal but it quickly became that by 2013 and 2014. I think immediately once a platform like that is shaping what people pay attention to, then aesthetics are dictated by that platform. I was in the art world as a career in 2011, 2012 and 2013. So much was about what you could Instagram and which gallery spaces you could post photos of. Suddenly, visual culture was a commodity on social media platforms. Sure, Facebook albums existed and Flickr existed, but this was a way to package the visual culture of your lifestyle onto the internet in a real-time way, hour by hour.

I think once that happens, that creates pressure to conform to that mechanism. Kara Walker’s installation is a great installation in a really interesting industrial space, but it also really helps that it’s good for taking pictures. You can place yourself in the context of it. For better or worse, you could pose between the two paws and the two breasts. It was a very easy schematic to follow, and that generates more currency online and shows more people — and then more people get attracted to come see it.

I think in a way it happens very quickly. By 2015, 2016 and 2017 you have restaurants that are Instagram traps. You have the Instagram walls with the angel wings — all this stuff that becomes visual currency online.

I know a lot of writers who’ll come to New York from out of town and post a photo on social media of them posting by Books Are Magic’s mural.

It really works. It’s a way to generate content around it, and generating content takes the place of marketing. You need to have a mechanism by which people post photos of your establishment, or your book or your painting. The Tesla Cybertruck is a visual commodity because people will take photos of it. And that takes the place of, perhaps, a more old-school mechanism of buying print advertising for the Volkswagen or billboards.

There’s an academic, Kate Eichhorn, who coined the phrase “content capital,” which I think is the most useful concept in the world because it’s what generates the kinds of content that can generate more content — or the kinds of people or ideas or situations that can generate content are more powerful. The content is the capital; the content is the resource and the engine and the currency. And what is generative of more content is more valuable, which is a wild but extremely real concept.

I remember reading not long ago that ByteDance was getting a foothold in the publishing world. I’m curious if that will work out for them or if it will backfire for them — in the sense that if they try to game BookTok too much, people will tune out.

When you create a platform, and you create influence in the space, the temptation is always to say, ” Okay — now I know the rules; now I’m going to play with house money, essentially, and produce my own products through this ecosystem.” I feel like it almost never works that way. I mean, we’re very vulnerable to gamified content that’s optimized to reach us, but there’s a line that you don’t want to go over and the line that you don’t want to go over is a book published by TikTok.

You might love BookTok for recommending other books to you, but you don’t want to read the book published by TikTok. That’s just like an aesthetic aversion that has not been breached yet. I just feel like it never really goes well. No one wants to listen to a band that Spotify produces. They could make it successful; they could feed it to tons of people but that’s gross. That’s a step too far.

Near the end of Filterworld, you bring up the fact that this moment in technology is not going to last forever. But it also feels almost increasingly difficult to imagine a world without it if only because, in a way that there wasn’t before, you have large companies with large financial stakes in keeping this whole system in place. Do you see there being a potential way out?

It’s a good question of whether they’ll shoot themselves in the foot faster or whether people will get bored faster. I think Twitter/X is doing both at once very effectively, alienating people very aggressively.

I want to say there’s a growing aversion to these kinds of algorithmic aesthetics and the idea that tech companies determine your taste and shape your identity. I think we saw how that went in the 2010s and hopefully we’ll create different relationships with it in the future.

The book is very critical, obviously, but I don’t think it’s apocalyptic. No one is making us look at TikTok; no one is making us think about what looks good on Instagram. We’re just so strongly incentivized to do it that it’s hard to escape. But I hope that people get off these platforms or move away from the things that the platforms most easily promote and instead look for culture in their own ways, get off the algorithmic path.

I find myself thinking a lot about the qualities that make a powerful work of art or a powerful encounter with a work of art, which is surprise, challenge, ambiguity and difficulty. Sources of friction have a way of developing our relationships with things in a deeper way rather than making them worse. The pitch of the algorithmic feed is, “Let me give you what you want. Don’t think about it too much, just look at the next thing if you’re bored.” And that erases a lot of meaning, I think. It erases a lot of our relationship with the culture we consume. I think we can and should move to the other end of that and slow down. Touch grass, essentially, in a cultural way. Go to your local punk venue or see a gallery show that you didn’t find on Instagram or something.

Can an Algorithm Tell Us the Saddest Song Ever Written?

It may not surprise you to learn that Spotify gave it a shotI hadn’t thought of the issues you bring up in Filterworld to be a labor issue, necessarily, but this argument sounds like it’s in dialogue with some of the arguments being made by both the actors and writers unions last year during the SAG and WGA strikes. The lack of transparency from streaming services strikes me as ominous — to name two services mentioned in your book, it isn’t nearly as easy to compare Netflix and the Criterion Channel in terms of viewer data in the same way that I can look at the box office numbers for, say, Barbie and Killers of the Flower Moon.

The lack of visibility we have into these platforms is part of what makes them so able to manipulate us. The sales pitch for the Netflix homepage was, “I, the faceless Netflix algorithm, will personalize this for you. I’m going to give you what you like; I know your tastes.” And most often it’s not true. A lot of this falls under the category of corrupt personalization, which is another academic term, which is the image of personalization without the reality of it.

So Netflix might say, “Here are some fresh movies for you.” And that’s just their top five latest productions that they make the most money off of, and it feels dishonest. I mean, it’s obviously dishonest. It’s not neutral, or at least numerical, in the way that Nielsen ratings or a box office number would be.

Our own passivity with these systems makes it really easy for us to be fooled by them. I think we’re gradually coming to understand just how much of this is corrupt personalization and is fake in a way. When I use Instagram lately, I like one thing and then I get such a high proportion of recommended content instead of what I actually follow. If I like one video of a guy cooking pasta in Puglia, then I get 18 more pasta videos. It’s like, who is this for? Just because I like a banana doesn’t mean I want to eat 20 bananas a day — and that’s the algorithmic equation. It turns us into robotic consumers. That’s the same as the robotic feed.

It’s been a while since I used Amazon for the bulk of my shopping, but I remember years and years ago I was doing some of my holiday shopping there and I bought a Bob Dylan CD for my dad. And then the next time I went there, my recommendations were every other Bob Dylan CD.

What’s the classic thing? I bought a microwave and then I got ads for 18 other microwaves because the algorithmic targeted advertising can’t understand that once I buy one, I don’t need one anymore. It thinks you want more and more and more. I feel like this falls under the umbrella of curation, right? The good curator, the knowledgeable person, understands that once you buy a microwave, you don’t need a ton more microwaves.

It’s almost like you want curation to be like the aisle right before the cash register in the grocery store where it’s a bunch of stuff that is very appealing and functional and you might just need it. I’m not going to pick up a microwave on impulse, but I might get some chapstick. That’s a smart human decision that is not really the way that algorithmic recommendations work in part because they can’t track you so deeply. There’s almost more predictive ability in you going to a cash register at a CVS than there is in you buying a microwave on Amazon, I suppose.

I was at MoMA yesterday because I wanted to see their Ed Ruscha exhibit before it closed. While I was there, I kept noticing how many of those paintings fit perfectly in the like square format of Instagram. And then I got very angry at myself for noticing that.

Right. It poisons your perception. Or, like I bring up in the book, when you’re on Twitter enough, your thoughts take the form of tweets. And that’s just how it works. Your eyes take on the form of Instagram and your sensibilities are conditioned by these platforms.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.