A blend of memoir, biography and criticism, The Book of James: The Power, Politics, and Passion of LeBron by Valerie Babb is an examination of LeBron James’s impact on the national discourse on race and the manner in which American views on Blackness have changed, and not changed at all. Below, Babb’s introduction to the book, which is out on November 28.

I am lucky to know a lot of sharp people I can share ideas with. It is interesting, though, that when I say “LeBron James” to some of them, I receive a dismissive I’m-not-into-sports response from those who tend not to mix Serena Williams with William Shakespeare. To others who understand how intrinsic athletics are to the background noise of our culture, when I say “LeBron James,” talk quickly goes from spectacular play to spectacular signification.

I might have been indifferent to sports, too, had I not come from a long line of folks who used Muhammad Ali or John Carlos or Wilma Rudolph as cautionary tales to show us younger family members where we stood in American society. I might have been completely uninterested in sports if I hadn’t grown up a New York Knicks fan (thank you for the sympathy, though mine were the 1970s Knicks), reading the Daily News from back cover (sports pages) to front (news headlines), and remembering the racial tension always on the fringes of a Celtics game. Green jerseys evoked not only a team but also memories of the Boston boycotts and violence in the run-up to public school desegregation so neatly captured in a Stanley Forman photograph taken in the same year as the American Bicentennial. In it, a young white man protesting the city’s busing plan, and holding an American flag on a pole like a javelin, threatens to impale a Black man in a three-piece suit being held up to his attacker by another white protester. Even with all this, if I somehow had managed to view athletics as peripheral to anything deeply socially meaningful, my experiences as a professor at Georgetown University would ensure I would never just shrug my shoulders at sports again.

Georgetown Basketball rose at the same time traditionally marginalized members of the university community pushed for more expansive and scholarly responsible curricula and programming. The sense that interlopers were undermining educational integrity played out in both the academy and the arena. The resentment directed toward the basketball team was very much a manifestation of resentment toward perceived gate-crashers entering a traditionally white space. It was yet to be public knowledge that the space many whites saw as “theirs” would not have existed had the Jesuits not sold 272 enslaved Black people in 1838 to save Georgetown from financial ruin. “Today the Society of Jesus, who helped to establish Georgetown University and whose leaders enslaved and mercilessly sold your ancestors, stands before you to say that we have greatly sinned,” Rev. Timothy Kesicki, SJ, president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, said during a 2017 Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope that included the descendants of those enslaved by the Jesuits. The apology was appreciated by the over ten thousand descendants, but an apology 179 years after the fact did little to erase the presumption of white racial superiority at the heart of resistance to a changing university. Georgetown was not unique here. Many Black athletes at predominantly white institutions faced resentment for their presence once off the field or court. The Power Five conferences — the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), the Southeastern Conference (SEC), the Big Ten, the Pac-12, and the Big 12 — the richest and largest athletic conferences, which include schools such as Vanderbilt, Duke, Northwestern, and Stanford, generated a combined $8 billion in athletic revenue in 2019 alone, mainly on the backs of Black student athletes. These athletes generally make up less than 10 percent of student populations at their universities but over 50 percent of Division I sports teams. Professor Billy Hawkins calls this “the new plantation model,” reinforcing racist notions of Black athletes as physically superior but intellectually inferior.

Once, while reading the Washington Post before a Georgetown basketball game, I found myself gazing at a three-quarter-profile picture of a smiling Patrick Ewing in jacket and tie. It accompanied an article about fans at a Providence College game holding signs saying ewing can’t read, and how the Georgetown center was greeted at a Villanova game with both a bedsheet proclaiming ewing is an ape and a fan wearing a T-shirt saying ewing can’t read dis. As a professor at Georgetown who knew how hard Ewing and other scholar athletes worked, I found the ignorant vitriol exhibited in the sports venues of higher education especially painful and unfair. Sadly, racist notions still dog Pat Ewing. The seven-foot-tall former Big East All-Star who played in Madison Square Garden, the former New York Knickerbocker whose retired jersey hangs from the arena’s rafters, was accosted by security asking to see his pass at the 2021 Big East Tournament while coaching his alma mater’s Georgetown Hoyas. I didn’t know it then, but all this was preparing me, sadly, for when my own son and his predominantly Black high school team took the court in predominantly white gyms to chants of “Here come the Black boys.” I saw many old race narratives in what Pat Ewing and my own son went through, along with the potential for physical violence and harm from opposing fans who believed these clichéd ideas.

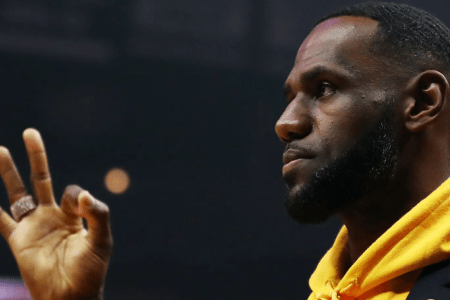

LeBron’s Biographer Explains the Business of King James

Brian Windhorst, the author of “LeBron, Inc.,” reveals the strategy James employs off the courtSports are a major engine of social narratives in US culture and a valuable gauge of social temper. Fields and arenas are theaters that both reflect and influence the beliefs of viewers beyond the athletic sphere. In The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, Howard Bryant insightfully describes how sports image-making mainstreams a particular set of values. The post-9/11 shift in political attitudes, he argues, were represented through taxpayer-funded military flyovers at football and baseball games and the increasing presence and celebration of uniformed military members. His points raise the question of why support of the military and its imagery is not political, just patriotic, while taking a knee to support racial equality is political and antipatriotic.

Such displays at sporting events encourage an unquestioning patriotism that worships American symbols while ignoring their histories. We are supposed to honor a flag that for most of the nation’s history flew over institutions barring access to anyone not white. We are supposed to take pride in an anthem even though it was written by a slaveholder whose “land of the free” did not include Blacks, a group he called “a distinct and inferior race of people.” But we are discouraged from taking pride in athletes who take a knee to point to the realities of Black lives lost to police brutality and to systemic, unequal social access. The unstated double standard of sports patriotism labels those athletes un-American. That sports patriotism leans right is evident in a quip made by football star turned sports broadcaster Troy Aikman to fellow broadcaster Joe Buck as both watched a flyover. Unaware of a hot mike, Aikman said, “That’s a lot of jet fuel just to do a little flyover.” When Buck responded, “That’s your hard-earned money and your tax dollars at work!” Aikman retorted, “That stuff ain’t happening with [a] Kamala-Biden ticket I’ll tell you that right now, partner.”

In their very configuration, sports manifest US racial histories. The fact that most of the owners of professional teams are male, white, and Republican donors, and the majority of players are not, is not coincidence but a result of existing hierarchies of class, gender, and race. It is not surprising, then, that sports reveal telling attitudes toward Blackness in US society. It is also not surprising that one of sports’ most prominent stars reveals just how much race, and particularly Blackness, is part of American DNA.

It’s such an American story: poor Black boy from “broken” home in poverty-stricken neighborhood makes good, then at the apex of his career “nigger” is spray-painted across the gate to his home. LeBron James is the protagonist in both these very American tales, one a success story the nation loves because it shows its benevolence, the other the latest installment in an ongoing chronicle of racial hatred. James is a particularly evocative example of the ways in which Black athletes are incorporated into American mythmaking, but also of how they put the lie to those myths. As one of the most visible representations of Blackness in national and global cultures, James is a target for those uncomfortable with the demographic shifts in their known worlds. LeBron hate has roots in the old myths that mire the US in racial polarization. His presence on the court, in media, in politics, and in the urban landscape he builds in his hometown, Akron, Ohio, provides many opportunities to show how timeworn narratives shape-shift to accommodate themselves to an era when racism increasingly goes by other names.

As a poor boy who made good, James incarnates the American dream and should be America’s darling, but the antiblackness that forces repeated racial reckonings makes him as hated as he is loved. Because of basketball’s Blackness (more about this later), the sport subjects James to a particular kind of antiblack scrutiny, but it also provides him with the means to undermine it.

I want to be clear as to what I mean by antiblackness. Antiblackness is a cornucopia of ideologies that have been used to facilitate the dominance of the many by the few. It utilizes skin color to create a global pigmentocracy enshrined into law, social practices, and institutions where those placed at the bottom of social ladders tend to have darker skin. Antiblackness doesn’t just affect Black people. The ideology behind the reductive Black-white divide easily mutates to make any group undesirable, as once indicated by directives such as “No Irish Need Apply,” “We Serve Whites Only—No Spanish or Mexicans,” “Gentiles Only,” “Chinese? No! No! No!,” “No Indians, No Dogs Allowed.” The racism felt by many — including immigrants, those of the Islamic or Jewish faiths, Asians vilified during a global pandemic, anyone deemed not white — is informed by a global antiblackness that teaches humans to rank skin-color difference, with lighter being better. At the start of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when many were trying to evacuate, antiblackness made it difficult for Ukrainian citizens and international students of African descent to leave as refugees. Some reported that white Ukrainian border agents and citizens groups forced them to wait while white Ukrainians were allowed to board trains to the border. Once arriving at neighboring nations, they again faced difficulty entering because of their race. Because its main aim is to sustain white privilege — not necessarily to the benefit of white people — the principles of exclusion behind antiblackness became a plug-and-play system where no new setup was required to adapt to a change in imagined enemies. The thinking at the base of antiblackness — that it is OK to shape laws and institutions to ensure one group’s dominance over others — also undergirds arguments over land use, voting, immigration laws, affirmative action, reproductive rights, sexual identities, and educational curricula.

A focus on antiblackness should not be viewed as ignoring other histories of unfairness; rather, it is a useful means of showing that those histories are interconnected, stemming from the ways antiblackness is foundational to the United States. Ideas of American freedom, citizenship, and rights were all constructed in opposition to Blackness. Indentured servants brought to the United States from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and other European nations were persuaded by antiblack ideology to support an economic and social system that yoked them to exploitative contracts that often lasted a lifetime but gave them the tenuous comfort of not being Black and thus not being a slave for life. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, antiblackness encouraged other racial and ethnic groups to mark their own belonging in US society by distancing themselves from Blackness. Antiblackness is larger than individual acts of racist hatred, language, or behavior that may easily be condemned, apologized for, and forgotten. Because it is so tied to worldwide histories of imperialism and colonialism, it is a systemic way of thinking that results in massive social and economic injustice perpetrated on those with darker skins.

In a perverse way, antiblackness makes how Blacks are treated in society an index of that society’s humaneness. The antiblackness at the root of George Floyd’s 2020 murder, for instance, sparked global responses because the unjust ideas at its base resonated with many. South Korean protesters at the US embassy held signs reading, no pride in killing black people. Pakistani Pasban Democratic Party members marched against his death with posters of his photograph captioned, let him breathe. In Frankfurt, Germany, demonstrators held placards declaring, your pain is my pain, while marchers in Marseille, France, proclaimed, laissez-les respirer (Let Them Breathe). Blackness resonates in spaces where unjust social hierarchies keep many different knees on many different necks. Pulitzer Prize–winning Illinois poet laureate Gwendolyn Brooks, in her poem “I Am a Black,” wrote, “BLACK is an open umbrella,” and recognized that the Black example provides much insight into other racial and cultural histories.

Over the arc of his career, LeBron James has been variously framed as the Black child of a Black teen mother, a runaway slave, and a Black jock out of his depth in political activism. His tendency to resist these projections by attaching an unapologetic Blackness to his brand has made him both a lightning rod for and a bulwark against antiblack sentiments. His rise to stardom coincided with a growing white grievance that vilified him because of its own fear of inevitable cultural change.

When we view James as a cultural subject and not just an athlete, unresolved tensions between Blackness and antiblackness become apparent. Rather than using celebrity to transcend Blackness, he uses it to give Blackness a place of prominence in American narrative-making, leaving a cultural record of how much Blackness is loved, hated, misunderstood, and just plain cool in an America that has changed and yet not changed.

Excerpted from The Book of James: The Power, Politics, and Passion of LeBron by Valerie Babb. Copyright © 2023. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.