Ian Fleming will forever be remembered as the creator of James Bond. But Fleming’s life barely overlapped with Bond’s leap into the world of cinema: Dr. No was released in 1962, and Fleming died two years later. That said, there have been no shortages of James Bond novels published in the decades between then and now — including novels from acclaimed authors like William Boyd and Kingsley Amis.

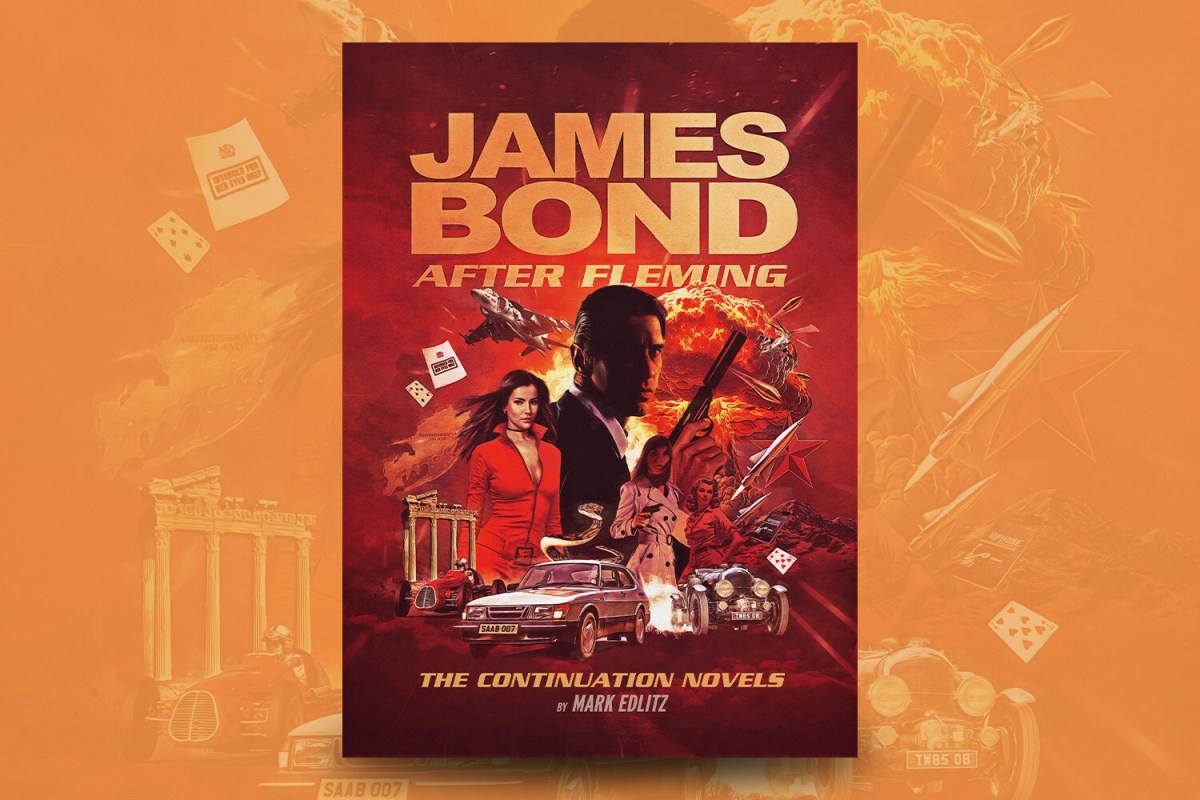

Mark Edlitz has chronicled lost, forgotten and overlooked moments in Bond history before — but with his new book, James Bond After Fleming, he explores the point at which James Bond left Fleming’s typewriter and began to be written by other writers. In an interview with InsideHook, Edlitz described the book as “a friendly and fun guide to the world of James Bond continuation novels.”

It’s an accurate description, and it’s fascinating to see how different writers have approached the character and the world of James Bond — from faithfully echoing Fleming’s original novels to opting for a more modern take on the character. Edlitz takes a rigorous approach to his subject, chronicling decades’ worth of permutations of James Bond — and broadening our understanding of what’s made this character endure for so long.

InsideHook: You’ve written two books before this one that also delve into the more obscure corners of all things James Bond-related. Had you always had this one in mind as well, or was there something that prompted you to start working on it?

Mark Edlitz: I wrote two other Bond books — The Many Lives of James Bond and The Lost Adventures of James Bond, which is about Timothy Dalton’s unmade Bond films. I thought I was done writing about 007. Then, I went off and wrote another book called Movies Go Fourth, which is about fourth films in popular movie franchises. You know, Superman IV, Jaws: The Revenge and Batman & Robin. At this point, I was looking for another topic to write about and I had a lightbulb moment.

I realized that no one had devoted a book exclusively to the post-Fleming Bond novels. There are a lot of 007 continuation novels. There are over 50 works that include novels about the adult Bond, Bond in his teen years, short stories, novellas, novelizations, and so on. I figured I could provide some useful information to those spy and Bond fans who were less familiar with the continuation works. So this new book James Bond After Fleming is intended to be a friendly guide through Bond’s many literary adventures.

Generally speaking, what are the different eras of Bond continuation novels?

After Fleming died, there was only one continuation novel in the ’60s, Colonel Sun. It was written by Kingsley Amis, a noted author in his own right but also a Bond fan. Colonel Sun includes a great torture sequence that was repurposed for the Daniel Craig movie Spectre. In the ’70s, we get a pseudo-biography of Bond, as well as two movie novelizations. Then things pick up. Throughout the ’80s and most of the ’90s, John Gardner wrote the continuation Bonds, followed by Raymond Benson who took over the gig. Benson wrote The James Bond Bedside Companion and he was a huge Bond fan. He also wrote six novels, three novelizations and three published short stories.

The Fleming Estate then paused the adult Bond novels and published five Books about Bond’s teenage years and a trilogy of books about Miss Moneypenny. Then a series of authors wrote a single Bond novel. Sebastian Faulks and Willam Boyd wrote a period Bond book and Jeffrey Deaver wrote a contemporary story. The Fleming estate published some more Young Bond books by Steve Cole and Anthony Horowitz wrote a trilogy of Bond books that were set during Fleming’s timeline. One is a prequel to Casino Royale in which James Bond has to investigate the previous 007’s death.

Now, we have a new series by Kim Sherwood about the other agents in the Double-O division. So that’s a lot of ground to cover and books to read.

At one point, you write that John Gardner’s books were “somewhat controversial among Fleming purists.” What brought this reaction on?

John Gardner wrote the Bond novels from 1981 to 1996 and he wrote 16 novels, 14 original books and two movie novelizations. That’s not quite two decades of Bond novels but it’s close. Gardner wrote more Bond than Fleming. Gardner’s first group of novels are traditional spy novels, with Bond going up against SPECTRE. As his run continued, Gardner broke away from the Fleming tradition. For example, in Never Send Flowers Bond tracks a serial killer to Euro Disney. Some Bond fans enjoyed his breaking the mold but some Fleming purists have resisted.

Is there as substantial a James Bond fandom as there are for, say, everything from Marvel Comics to the television show Supernatural? Or does it have a different shape than some other pop-culture communities?

Bond is huge. It’s a multi-billion dollar business and it’s the longest-running continuous movie franchise. At one point, they estimated that a quarter of the world’s population has seen at least one Bond movie. The franchise is not just movies, there are video games, cartoons, comics, YouTube Channels like The Bond Experience devoted to lifestyle and clothes, and of course books. The movies are the most popular and most visible aspect of the franchise.

What did your own research for this book look like? Were you also delving into the writings of, say, Kingsley Amis or William Boyd to see how their Bond books fit in with their own bibliographies as well as with Fleming’s?

As for research, most of it was concentrated on the novels themselves. I’m less interested in writers’ — or any other artists’ — personal history than in their work. I also wanted to provide a history of the continuation novels and how they came about. At first, it wasn’t certain that Bond would continue in literary form after Fleming’s death. Fleming’s widow was against it. So all that required a lot of research.

James Bond After Fleming also encompasses some unrealized projects like the unpublished Per Fine Ounce. How do you go about learning about works like this, where there might not be an extant copy in existence?

Per Fine Ounce is an interesting case. After Fleming died, the estate entered into contracts with three authors to write Bond-related works. Two of those books came to fruition. First, there was The Adventures of James Bond Junior 003½ by Arthur Calder-Marshall. That book was about Bond’s nephew who goes by the nickname 003 ½. Kingsley Amis wrote Colonel Sun, which a lot of Bond fans love and think is one of the best. Geoffrey Jenkins was contracted to write Per Fine Ounce. However, once Jenkins submitted the manuscript, the Fleming Estate declined to publish it. I love researching and trying to find out information that even hardcore fans might not know. In the end, I was able to devote an entire chapter to it.

Another thing that struck me about this book was the ongoing motif of post-Fleming writers having a difficult time getting specific dates and ages from Fleming’s novels. Do you get the sense that Fleming was being intentionally vague about this, or did it feel more like an editorial oversight at the time?

You are correct, as a general rule, the novels avoid pinning down dates and Bond’s age. I believe that Fleming intentionally avoided it because he wanted to keep Bond perpetually young. If Bond ages too fast, he’ll turn 45, which is the service’s mandatory retirement age. Fleming and other continuation writers provide some clues. In William Boyd’s Solo, Bond is celebrating his 45th birthday party. Generally speaking, the idea is to keep Bond timeless.

One thing that I found interesting about the novelists who have written James Bond after Ian Fleming was the fact that more than one have also chronicled Sherlock Holmes’s Moriarty as well. Do you think there’s something about that character and Bond that have more in common than some would expect?

As you point out, John Gardner and Anthony Horowitz have written continuation novels based on Arthur Conan Doyle’s characters. Sherlock Holmes is arguably the world’s most famous detective and Bond is the world’s most celebrated spy. So both characters are the big brass ring in their genres. Also, in both cases, Gardner and Horowitz had to deal with the Doyle estate, just like all Bond authors have to work with the Fleming estate. Authors have to be able to craft a new story while being faithful to the original creation. It’s a difficult task.

Coming back to John Gardner for a moment — one of the threads of James Bond After Fleming seems to be that of Gardner finding a way to put his own distinctive spin on the character of James Bond. What else struck you about his years-long run on the character?

Gardner said that he wanted to update Bond’s spycraft and make it more modern. No more talcum powder on briefcases to see if something was touched. Instead, Gardner wanted to use all the high-tech and cutting-edge technology available to him. He was also a Royal Marine commando during the war. So he had all that experience to bring to his writing.

A New Book Reveals James Bond’s Vietnam War-Era Origin Story

“The Lost Adventures of James Bond” explores the secret agent’s secret historyYou brought up James Bond comics a bit in The Lost Adventures of James Bond — is that something you might write about at greater length in a future volume?

In The Lost Adventures of James Bond, I wrote about a few Bond comics including German Gabler’s 65 issues in Spanish. Gabler’s a great writer and artist from Argentina. Some of those works were faithful adaptations of Fleming’s novels and short stories. But some of them were brand new stories with Bond in some unlikely situations — such as Bond versus a Yeti. So not your typical Bond adventures but super-fun, especially if you don’t mind a little (or a lot of) creative license. Anyway, the Bond comics are fun so it’s a subject worth exploring.

While reading and researching this book, did you uncover any information that surprised you?

Absolutely. Two things come to mind. Not all the Bond stories are still in print. Some are only available as eBooks and others are not available at all. I also found a couple of authorized short stories that I didn’t know about, including two that included time travel. Time travel!

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask a bit more about the time travel element…

William Boyd wrote two very short stories to promote Solo. In both, Boyd (the author) travels back in time to interview James Bond (the character) about his missions. Of course, the stories are tongue-in-cheek and aren’t meant to be taken seriously. Similarly, Raymond Benson wrote a short story where Bond is sent on a mission to the Playboy Mansion and receives spy gear from Hugh Hefner.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.