The one time I met Coach K — I was a kid, waiting for him to sign a mini basketball — I asked him who was the hardest worker on the Olympic team. Without taking a second to think he replied “Kobe Bryant. Kobe is always the first guy in the gym.”

That didn’t come as a surprise to me at the time, and it probably wouldn’t to you now. Kobe’s name, along with those of a half-dozen other maniacally prepared pros, has long been synonymous with work. First to practice, last to leave: Mamba mentality. There is no such thing as extra credit in this doctrine; there are only more opportunities to put in more work. If you fail to cash in on those hours, you shouldn’t be confused when you lose.

In fact, right after a loss is the exact time you should be getting back to work. Because clearly, something was lacking. You needed more technique here, or a quicker burst of speed there. Sportswriters love the “he got right back in the cage” narrative. When Odell Beckham Jr. first burst onto the scene, back in 2015, ESPN The Magazine shared a mythical account of how the wide receiver processed his LSU Tigers’ BCS title defeat to Alabama, which was played in the Superdome. He was a freshman at the time, and after the game he reportedly ran sprints up the nearby levees until 2 a.m.

Sports are so divorced from the realities of a normal 9-5 that it’s often easy to forget the ways in which athletic professions mirror the demands and expectations of the American labor market. But there are resonant comparisons to be made. In the pandemic era especially, the hardest-working employee has simply become the one most likely to check their email at any hour of the day. This is not seen as overwork, but just work — if at least a select few are doing it, and thriving (publicly, at least) surely others can step up in the name of corporate success.

But we’ve surely seen enough trending LinkedIn stories on “employee burnout” to know that this is no way forward. A similar sensibility exists in sports, at both the professional and amateur levels. Spurred on by the greats of the game — who, in well-documented fashion, are known to never settle for anything less than the best; who play through injuries; who attempt crazy expeditions; who yell “Who’s gonna carry the boats at the top of their lungs” while incline-benching to the tune of 100 repetitions — too many athletes fall into a trap where overt overtraining becomes training, and training becomes not enough.

There’s a name for this phenomenon, in fact. It’s called “overtraining syndrome,” and it’s a condition marked by mental fatigue, persistent soreness, poor sleep, appetite or mood swings and susceptibility to illness and injury. When athletes don’t give their bodies a break, they start to break down. You’d expect, in an age where recovery fitness is finally becoming a household concept (think massage guns, compression sleeves, plunge pools, etc.) that serious athletes would know better than to overtax their bodies. But it’s not like the pull to perform has changed. Some hyper-motivated athletes find themselves willing to flout modern training sensibilities if it means proving to themselves (or others) that they’ve done enough to prepare for a game, match or race.

According to ultrarunner Dylan Bowman, who competes for Red Bull, overtraining syndrome (OTS) is a result of pervasive, “misguided insecurities” among athletes. “We’re inherently hard-working people who want to be at our best,” he says. “And too often, we conflate training longer and harder with being better. Rest is seen as laziness, which is anathema to the personality of high level athletes. Unfortunately, overtraining leads to underperformance, which often makes athletes think they just need to train harder. So it can be a really dangerous spiral without the right guidance.”

Bowman says that a legacy of overtraining is closely intertwined with the trail running community. He’s managed to reel himself in at crucial junctures, but he can’t say the same for some of his peers.

“Many of my friends and competitors have stepped over the line severely, resulting in several years of injury and seemingly inexplicable drops in performance. Some were never the same again. My personal opinion is that OTS is more correlated to overall racing volume than to training volume. In other words, it’s the acute stresses of race day that require total respect and deep recovery. If these efforts are stacked too close together, over periods of months or years, it can lead to horrible consequences. The scary thing is that over-racing and over-training are often sustainable for two to three years, sometimes with great results, before the athlete experiences an energy implosion. So athletes really need to be aware of leading indicators like lack of sleep, weight loss, poor performance and lack of motivation. Not interpret such signals as personal weakness or inadequacy.”

Certain sports — and certain levels of sports — are obviously harder on the body. But OTS is agnostic to concentration and skill level. It’s a psychological issue, with physiological manifestations, which means it can impact just about anybody…even people who do parkour. Christian Zelder belongs to the New York City parkour community and believes it’s rife with overtraining.

“We all push each other to be our best,” he says, “but we don’t really take into consideration the possibility of being fatigued until we become fatigued. After training three days in a row, we start to feel it and we’re not performing our best. Which is really dangerous. Our muscles can fail us when doing a flip, a fairly far jump or height drop. There’s always that risk of rolling an ankle when your muscles are that worn down.”

It’s possible that his community simply needs more standardization, and more education on best practices. Zelder acknowledges: “The parkour community is only just getting going. We’re just starting to have some parks installed and find our way into after-school programs at certain schools in NYC.” But even in established sports, with well-funded camps and well-regarded coaches, OTS has flexed its maw. Nike’s Alberto Salazar, who ran the groundbreaking Oregon Project for nearly two decades, was ousted in part for his outrageous training demands. They were so stringent that one of the best prep runners ever, Mary Cain, saw her career crumble before her, as outlined in a famous op-ed for The New York Times three years ago. In an attempt to be a good soldier and overtrain alongside the rest of Nike’s most elite task force, Cain lost her period for a year and broke five bones.

A cult-of-personality coach, the allure of signing a contract, an institution that’s always “done things a certain way” — any or all all can contribute to a case of OTS that an athlete never envisioned or wanted. Robert Herbst, a 19-time world champion weightlifter who now oversees drug testing at the Olympics, explains that some lifters, training to impress, can experience a sickness known as yoke flu. “Carrying more than triple bodyweight on a yoke can so depress the central nervous system that you develop flu like symptoms,” he says. “You can also develop overuse injuries such as tendinitis or, as tears where under-recuperated muscles and points of attachment give out under the load.”

It’s especially concerning if the athlete is young and impressionable. When Harvey Meale, a 27-year-old Australian, was just 16, he juggled high school with over 40 hours of volleyball training and matches each week. He was in the Volleyball Australia Elite Development Program, and poised to become one of the country’s next best volleyball export. A decade later, he says he can only thank those days for his early onset male pattern baldness and low testosterone levels.

“Five nights a week after school, I’d drive to practice, where we’d have approximately five hours of court-work training and then an additional two hours of strength and conditioning, under some of the finest coaches in some of the best facilities in the country. On the weekends there would be matches or training camps on both days, giving me almost no chance to rest. At some point, I stopped improving. I wasn’t getting better so I figured the best thing to do would be to get up early and do some additional weightlifting so I could get stronger and make progress in the gym.”

Meale says he’d get up every day at 4:30 a.m. to perform squats at home before going to school. That’s difficult enough after an average night’s sleep — but Meale was staying up until 2 a.m. most nights to finish assignments and study for exams.

“I’d get to school each morning and buy a double-strength iced coffee just so that I could keep my eyes open,” he says. “I was soon addicted to caffeine at age 16. The thing is, I didn’t know overtraining was even a thing back then.

I just thought if you weren’t improving, you weren’t working hard enough. I assumed the only solution was to spend more time, do more reps, sacrifice more sleep. I grew quite depressed during my senior year and, despite successfully making the national youth team and touring to international tournaments, I made almost no progress that year in terms of my numbers in the gym or technical abilities in volleyball. When the elite development program ended for the year, I was so exhausted that I quit volleyball entirely.”

These days, Meale is still struggling to wrap his head around the 18 months of insane overtraining he experienced at age 19. His only fond memory from that time? Getting to crawl into bed at the end of yet another very extremely day.

“I simply didn’t know better. And the astonishing part is that my coaches didn’t seem to either. We had elite sports performance coaches working with us every day — at times we were required to log all the food we consumed for weeks so coaches could see what our diets looked like — but neither the head coach nor the strength coach ever thought to ask about whether we were tired.”

While Meale was at the mercy of a manipulative system, some athletes have the cache (and a team that respects the latest in sports science) to actually make a change, and prevent a career from going off course. Another Red Bull athlete, skier Daron Rahlves, remembers how the United States Ski Team would practice in the late nineties, before a chance summer training camp in Chile, in 2000, with the Austria Ski Team. The Austrians, who tended to handily beat the Americans in competitions, had an entirely different training regimen.

“The Austrians focused on high intensity and lower volume on hill and recovery sessions every day after skiing, even on days off. They were the most dominant team with the top athletes and we took notice. Meanwhile, we always went hard on and off the hill with volume,” Rahlves says. “[We needed] to acknowledge recovery as part of the training plan and then incorporate it into the program…It’s not just resting, eating, hydrating, getting the needed sleep and mindset or mediation work, but focused physical recovery sessions to flush out any lactic acid. The goal was to eliminate all lactic acid in the system for full muscle recovery. Recovery is a huge focus of any top athlete. This was mostly done on the spin bike, in water, stretching and massage.”

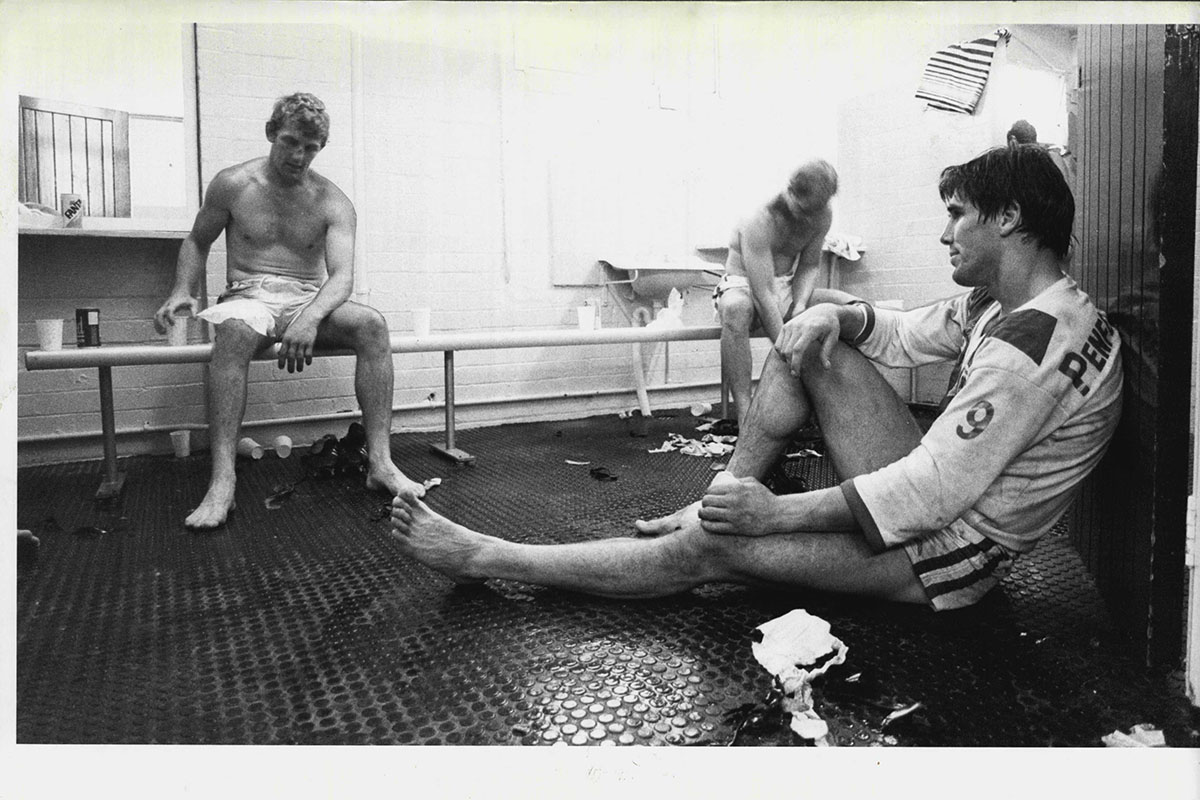

OTS may not be a permanent bodily condition, but it can certainly ravage the body while it’s there. What can be permanent is the choice it dictates. When sport becomes depression, and the gym becomes a hellscape, who in their right mind would want to continue training? Who would want to continue playing?

Those turn-of-the-century Austrians had the right idea: periodization. Dr. Robert Neff, a sports psychologist who’s trained Olympic gold medalists and currently assists USTA Player Development at the National Training Center in Carson, California, contends that “as long as physical injuries have been avoided, overtraining syndrome can be fairly quickly reversed with proper periodization.” It’s a more balanced and thoughtful method of devising a training regimen, basically. Instead of a runner tackling a hilly course at his target 5K pace every single day (an extreme example, but you’d be surprised), his weekly slate would include long runs at conversation pace, cross-training days on the bike and most importantly days off.

“Coaches are rarely trained to design these sorts of regimens,” Dr. Neff says, “and those who are struggle to maintain them because the upkeep can be time consuming. They involve planned overloading and recovery, which allow the body to experience “supercompensation.” That refers to strength improvement after muscle breakdown, and then adequate rest. In short, the athlete ends up strong after temporarily breaking down the body. Periodization builds in the necessary recovery by not only scheduling rest but also by reducing the training load (intensity, frequency and/or duration), adding cross training (other related sports or activities), increasing mental training (visualization, mindfulness, etc), and reducing travel and competition.”

Consider: if professional coaches are ill-equipped (or ill-motivated) to build schedules that reflect the dynamic nature of an individual athlete’s needs, goals and general exhaustion, what’s can one expect at the high school or even youth levels?

In addition to a regimen that passes the eye test, proper fueling is critical. OTS is generally a bedfellow to energy deficiency. Overtrainers often end up eating less — or are instructed to eat less; for instance, Cain had to eat cereal bars while hiding in closests, terrified that her coaches would hear the crinkle of wrappers — due to the changes in appetite and mood that accompany beating one’s body into the ground. But a lack of requisite carbohydrate fuel leads to poor performance, which leads to even more training, which leads to…you get the idea.

Dr. Neff recommends making meals non-negotiable: “Inadequate nutrient and caloric intake is one of the main causes of energy deficiency. This of course needs to be remedied quickly before the athlete can hope to get back on track and make performance gains again. Immediate rest and planned meal times are often necessary to insure overtraining syndrome can be stopped and reversed.”

Dr. Amy Saltzman agrees. The author of A Still Quiet Place for Athletes: Mindfulness Skills for Achieving Peak Performance and Finding Flow in Sports and Life , she also advocates for what she calls an “energetic bank account,” in which athletes continually “check their balance,” determine whether choices might be considered “deposits or withdrawals” and long-term, make a conscious effort to stay in the black. She says:

“Examples of deposits include a good night’s sleep, a healthy meal, listening to music, hanging out with good friends, a good stretch and roll out, a bath, watching your favorite show or inspiring videos, relaxing with your pet, a recovery workout, a massage, an early date night, and resting in the Still Quiet Place. Examples of withdrawals include an intense workout; getting sick; a major project, test, or final exam; an argument with a family member, friend, teammate, or coach; breaking up with your boyfriend or girlfriend; and a major change or illness in your family or on your team.”

Notice that ordinary life events make the list, too. Withdrawals are more than just HIIT sessions on a spin bike. The body can’t help but respond to the stress of life’s non-athletic struggles — it stands to reason that these challenges (many of which can dramatically impact mental health), must be factored into any common-sense training program. Sometimes, it just means that the training program should end. At least for a little while. Being a human is hard enough without having to be an athlete all the time, too.

Bowman has the right idea. At the end of a running season with Red Bull, he takes one mighty step back. “I try to totally decouple from my athletic identity for a couple months every year,” he says. “I’m still staying active, but I’m not tracking data or following a schedule, just doing it for the love. I need these periods of deep rest in order to replenish the well of energy and motivation necessary to be my absolute best when it matters most.”

Consistency doesn’t have to be all-consuming. I was charmed, despite myself, by a recent Logan Paul interview. He asked Arnold Schwarzenegger why, at 74-years-old, he still goes to the gym each day. Schwarzenegger calmly replied that it’s for the same reason that he has breakfast everyday, that he still goes to sleep each night. It’s who he is. It’s what he loves to do. And he knows how to do it right.

Ultimately, it’s possible to do something every day to make yourself a better athlete, to feel like your training is headed in the right direction. That “something” should not — for the sake of your long-term physical and mental health — always look like a hard workout. It can be a shoot-around, a gentle stretch or a half hour with a book. It all counts. It’s customary to celebrate and repeat the myths we hear about athletes putting in extra time, in their trademark torturous ways. But with ONS a real and present threat, for athletes of all ages, let’s get in the habit of highlighting the rest days, and not just the records.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.