You had to be there. But you probably weren’t because only 200 people were there.

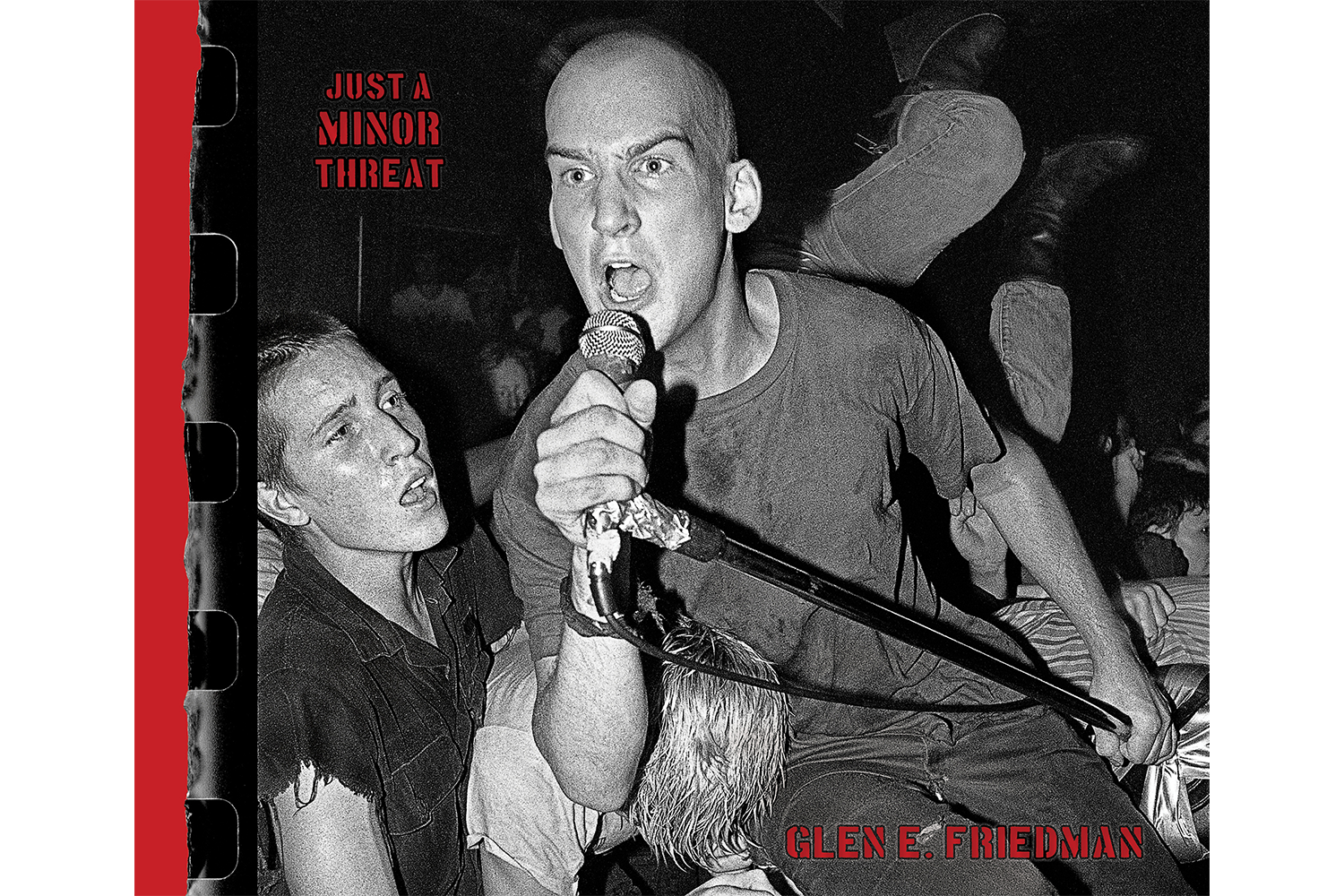

Minor Threat’s legacy is massive. The hardcore band laid a blueprint for all DIY music in terms of integrity and quality. Their sound can be heard in bands headlining arenas in 2023 and their ethics are emulated by most every touring band playing house shows across the globe. But very, very few people actually saw Minor Threat live. The new book, Just a Minor Threat: The Minor Threat Photographs of Glen E. Friedman, features some of the most iconic shots of the band, plus more than 100 photographs most people haven’t seen until now and essays from musicians like Rage Against the Machine’s Zack de la Rocha.

We spoke with photographer Glen E. Friedman about shooting the legendary band well before they were legends and how Ian MacKaye may be the best D.C. has to offer.

InsideHook: The more I think about the scarcity of Minor Threat’s catalog — one LP, three EPs, less than 60 minutes of recorded material — and your shots of the band, about 200, fewer than six full rolls of black and white film, it seems kismet that 140 of those shots, most of which were never seen, make up this book.

Glen E. Friedman: Correct. I mean, you know, I’m pretty proud of it, actually. That’s how I’ve always shot, I shoot it to count. Film was not a resource I had a lot of access to. You had to pay to shoot, each image counts — you’ve got to get it processed, you’ve got to pay for the film, and you’ve got to get prints made — and there really weren’t any places to have stuff published back then, there was no way for people to see them. You’re just doing it because you love it and, hopefully, sharing it in the few places that people might be able to see it, but there’s no guarantee and usually they didn’t. That’s why we have these books.

It seems that folks like you have really helped cement these guys’ legacies.

In a way it does. I wouldn’t say Ian MacKaye so much as I would say some of the skaters and stuff like that, because I think Ian’s legacy goes way beyond what I’ve done.

All the subjects I shoot, they inspire me to do what I do. And I know that the images become iconic and they speak to a lot of people. And that, perhaps, does what you say. But I think that with Fugazi [Friedman also has a book of Fugazi photographs] and Minor Threat, because of their output and their reputations and their interviews over the years, they speak for themselves.

Luckily, we do have these beautiful images that I was creating over the years with the subjects, that tell the story and make it more vivid for people who weren’t there and even for people who were there. My duty was to take an hour- or half-hour-long performance and boil it down, tell the story that would help people feel what I was feeling and what I thought was necessary to inspire other people the way I was being inspired at those shows.

Is there an L.A. or New York equivalent of what you think Minor Threat or Fugazi means to D.C.?

The Los Angeles and New York scenes were, you know, they’re bigger populations, they’re bigger areas. I would credit Dischord and their label for being something that represents D.C. more than just the two bands, but those bands have international respect, right? Minor Threat’s songs were incredible and the anthems were incredible.

One of the great things that we have to look at is their incredible sense of integrity — both of those bands, Minor Threat and Fugazi, didn’t ruin their legacies. When Minor Threat was done, they were done. Fugazi has never officially said they were done, they just took an extra-long hiatus and probably won’t do a public performance again. I don’t know, though. You never know. They have this incredible sense of integrity, which I think makes them unique to any band anywhere in the world.

New York punk rock in the ’70s was a very incredible thing. After that initial boom, it was just — I don’t even know how you describe it — but it wasn’t interesting to me. There were some great moments and there were some great songs and there were some good bands, for sure. But nothing to the level of inspiration and integrity from what I saw to match Minor Threat.

Ian is a fifth-generation Washingtonian and has kept his life there, not only his roots. He did not move away. There’s a lot of respect to be given to that man and his sense of integrity with Dischord Records, with Minor Threat, with Fugazi, with Embrace, with The Evens. They’re really all fantastic, aren’t they? If you listen to them, it’s pretty amazing. But that individual is beyond — that’s a special human being right there that you guys have, he is a national treasure. If you look at the output and the influence and the inspiration that he provides for so many all over the world and the way he handles his life and business, it’s something to be admired and appreciated. That’s Washington, D.C., you know, not the federal city, he’s the real deal, the people who live there forever. There’s nothing like Minor Threat and Fugazi in Los Angeles or New York or fucking anywhere.

Like It or Not, Indie Rock Is Getting Old

But bands like The Hold Steady and The National are embracing their Dad Rock status — and celebrating rare ninth albums after decades of playing togetherThe book isn’t just shots of the band in D.C. There are photographs of them playing in L.A. and New York, too. But if you don’t know what you’re looking at, it’s obvious that Ian MacKaye has the crowd, he’s able to captivate an audience and bring them in a way that makes location meaningless.

Ian is the definition of “down-to-earth.” I mean, he is the earth itself, isn’t he? I think that feeling translates through his music and the way he presents himself when he is performing in front of people. It’s just very human and I think people relate to that and they feel that.

There are just three live shows in the book, besides the photographs that we made in between shows or just when I was down in D.C. It’s one show in Los Angeles (at The Barn), one show in Washington, D.C. (at the original 9:30 Club) and one show in New York City (at CBGB), and they were all phenomenal. They were all shows that to anyone who saw them, it was life-altering.

The bands prior to Minor Threat, punk rock bands that were fantastic — Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Bad Brains — there was something about all those bands where you looked up to them on the stage. As much as punk rock was about breaking down that barrier between the audience and the performers, their reputations preceded them. When Minor Threat was on the stage, you looked straight at them. It didn’t even matter if they were higher up. There was something about their presence, their youthfulness, I don’t know what it was, but you just felt like [Ian] was one of you more than a performer performing for you.

You’ve also shot some of the biggest bands in the world when they were the biggest bands in the world, like Run DMC, LL Cool J and Beastie Boys. Did you approach any of them any differently than when you were shooting Minor Threat?

I think when I shot and made photos with those other groups, I had a deep appreciation for what they were doing. So my approach was always very similar, the only difference was that sometimes the stage was big, a little too big. To get a lot of character was difficult when you’re not able to be close with the group and with the audience. So I concentrated with those groups more on portraiture, because no one was that close to them.

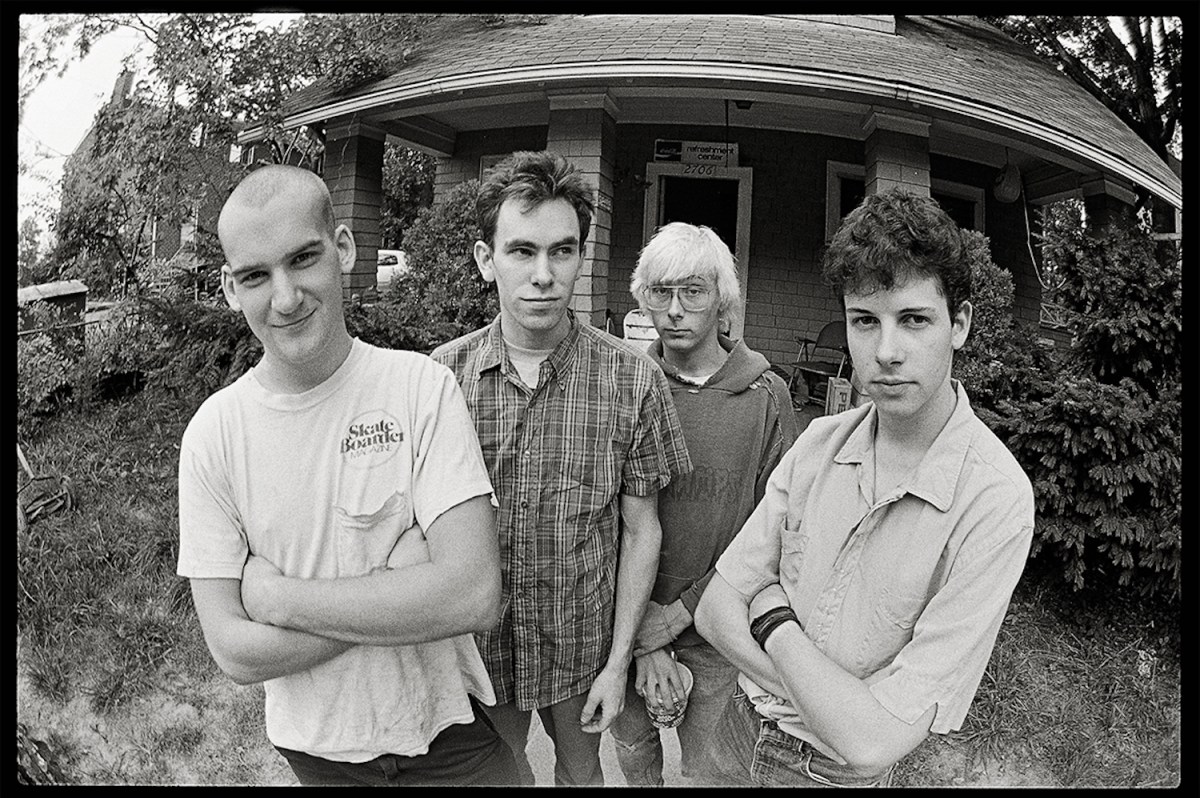

I feel like I have to mention the Dischord house photo, the Salad Days photo. It might be the most iconic shot of a band sitting on a porch?

It’s become one of the most iconic punk rock portraits, even though it’s so suburban, in a way. It’s definitely had its — I don’t know what to call it — I don’t want to say “impact,” but it definitely speaks to a lot of people. People really love that image. There’s a lot of character in it. And, you know, it’s a beautiful image. And it tells a story a little bit. I guess I can’t explain that one.

In the new book I show all the outtakes and that one was the perfect shot, in my opinion. It’s well composed, the character looks great. For some reason, people just latched on to it. People visit there almost every day to sit on that porch and take that same picture. And if they’re lucky, Ian is working. And they might get him in the photo.

I can’t really explain it other than people relate to it and they love it. That’s cool.

This article was featured in the InsideHook DC newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Beltway.