Terroir is a word and a concept that has come to represent many different things. Like organic, natural and bacteria, terroir is an often-used, frequently misunderstood term with a very specific definition.

Terroir is the combination of natural factors, including soil, climate, sunlight and topography, imparted via a very specific taste and flavor. Obviously, a Cabernet Sauvignon grown in Napa will taste completely different than a Cabernet Sauvignon grown in the Finger Lakes. But even comparing two Cabernet Sauvignons grown in vineyards that are right next to each other will deliver flavors and aromas that are utterly distinct from each other.

That’s because, as incredibly powerful as natural forces are, the role of human beings, and how they choose to care for those grapes, pick them and then herd those elements into the bottle can have an outsized effect on what lands in your glass.

While the recent “more land than hand” movement has served as a much-needed correction to several decades of over-industrialized wine farming and making, the pressures of climate change are making winemakers reconsider the merits of certain forms of intervention in the vineyard and cellar.

In the Vineyard: Cover Crops

For much of the 20th century, most vineyards looked pristine: if there was grass, it was bright green and short. Heavy doses of chemicals were deployed to destroy “weeds,” and wildflowers and wild grasses were viewed with suspicion. But as extreme weather — from wildfires to hail storms to deep freezes and extreme droughts — devastated wine country, many growers turned away from chemicals and embraced a more natural approach to farming.

Cultivating cover crops isn’t simply a matter of letting the vineyards’ grasses grow at will. Instead, it’s a process of analyzing what the soil and grapes need and planting accordingly.

“Every piece of work we do in the vineyard influences the terroir,” says Luisa Slotwinsky, assistant winemaker at Thomas Niedermayr Hof Gandberg in Alto Adige, Italy. “Chemicals and herbicides destroy terroir. I see it as our job to preserve it. One thing we use to manage diseases and pests without the negative impact of chemicals is cover crops.”

Viticulture, she argues, is a monoculture, and cover crops allow vineyards to be healthier and more fruitful, without needing chemical intervention, which will not only kill the “bad” fungi and vine-harming microorganisms in the vineyard, but also the “good” ones.

“Conventional viticulture with chemicals wipes out all of the fungus,” Slotwinsky says. “But when you look at healthy soil, fungi play an essential part. They stabilize the connection between soil and vines. They make the soil healthier and more productive; they preserve water and keep the temperature down during heat spikes.”

The Niedermayr team uses a wide variety of cover crops to enrich the soil’s microbiome and offset any deficits it may have. They also harvest some of their cover crops for traditional South Tyrolean dishes.

“We use corn, grains, pumpkin, zucchini, beet and potatoes as cover crops, in addition to more traditional herbs and plants,” Slotwinsky says. “We check our soil and see what it needs in terms of biodiversity, nitrogen and the like, and we plant accordingly.”

Others use cover crops to enhance the soil’s vitality, replace classic animal fertilizers and react to Mother Nature’s latest antics.

At Querciabella in Chianti Classico, vineyard director Marco Torriti began transforming their vineyards with cover crops as the estate moved toward a more biodynamic and completely organic approach to farming in 1998. Out with chemicals and animal manure, in with a carefully calibrated blend of cover crops.

“We use a mixture of over 30 useful plants, medicinal herbs, legumes and grains specific to each vineyard to enhance the health of our vines,” explains Emilia Marinig, marketing director at Querciabella. “Other plants help boost the soil’s vitality, retain moisture, improve soil structure and protect it from erosion.”

Because cover crops have a shorter growing cycle, they can also make adjustments on the fly, taking cues from the whims of that year’s weather.

“During vintages with less rainfall, we opt for cover crops with deeper roots to extract more water from the soil,” she says. “And in vintages with more rain, we may use cover crops that are better at absorbing excess water and preventing erosion. During hotter vintages, we may choose cover crops that provide more shade to the soil and help retain moisture.”

These Lab-Grown Grapes Could Be the Future of American Wine

Baco Noir, Catawba or Cayuga? They’re elegant, exciting and climate-resistant.In the Vineyard: Soil Pits

Digging into the vineyard and examining the soil has also become a strategy that many producers deploy in a bid to boost productivity and vine health, even in challenging conditions.

When you look at a vineyard’s topsoil, you can see its texture and color. But you have no way of seeing what lies beneath: more of the same, or perhaps layers of limestone? By digging pits (usually about five to six feet deep) around the vineyard, growers can assess the layers of soil and test each layer’s composition, color, texture, plasticity and pH. By understanding what lies beneath, they’ll be able to make better farming choices, says Deyvani Isabel Gupta, winemaker and viticulturist at Valdemar Estates in Walla Walla, Washington.

The vineyard team hired geologist Dr. Kevin Pogue to dig and analyze 16 pits. “All three of our vineyards had extensive soil study; soil pits were dug out in several areas, especially in the North Fork, as the slope and soil composition varied quite a bit throughout the site,” Gupta says. “These pits informed not just the variety we planted in that area, but also the rootstock chosen and its clay, salt and water tolerance.”

The findings — 30% clay in the North Fork property with some calcium and salt presence — informed their choice of rootstock.

Enrique Tirado, technical director and CEO at Chile’s Vina Don Melchor, also digs soil pits to ascertain how each area of the vineyard should be planted and farmed.

“Every 10 years we open 40 to 50 pits on our 127-hectare estate, and every other year we open five to 10 to obtain information on root growth, nutrition and other information that will help us achieve the best quality in each parcel,” Tirado explains. “We now have divided the vineyard into seven parcels, and 151 mini-parcels that we manage differently.”

The practice, Tirado says, ensures that even in unusual vintages, with farming adjustments following soil analysis, they can achieve “great quality, complexity and final expression in the Don Melchor wine.”

In the Vineyard: Mapping the Soil

Setting out to create an electromagnetic conductivity map (ECM) of the vineyard has become an interesting offshoot of several soil pit projects. While the notion of an ECM may sound hopelessly opaque, studying soil’s electrical conductivity is fairly straightforward. The ECM measures soil salinity, moisture and depth. This, in turn, can help growers understand how deep down their vine’s roots will go (the deeper, the more drought-resistant) and how much water the soil will retain.

“We dig soil pits to help us understand the soil profile,” says Cristian Vallejo, who finds an ECM helps guide choices at Vina VIK in Chile’s Cachapoal Valley. “We also analyze the local climate. But to be able to select what type of grapes we want to plant, we map the electromagnetic conductivity of the soil, plus the slope and sun exposure.”

The Santa Rosa, California-based Jackson Family Wines has about 10,000 acres planted to vines in California, Oregon and Washington. Their vineyard managers utilize the Geonics EM38-MK2 ground conductivity meter in addition to their soil pits.

“These sensors map soil changes so that in conjunction with soil pits, our vineyard team can compare and analyze those data points to ensure we make precise decisions on farming methods, rootstock recommendations and other considerations,” explains Craig McAllister, head winemaker at Jackson Family’s La Crema.

In the Vineyard: Targeted Soft Pruning

At its most basic, when a vine is pruned, portions of the branches, foliage or fruit are removed to maintain the plant’s size and shape and encourage productivity. Simonit & Sirch, a pioneering pruning consultancy founded in 1998, has set out to elevate the practice of pruning into an art form. (The wine world has taken notice: Yquem, Latour, Louis Roederer, Domaine Leflaive and Muga are among their clients).

Marco Simonit and Pierpaolo Sirch created their system when they began noticing that some vineyards were deteriorating faster than others.

“We began to question this, and why modern vine training practices seemed to exacerbate it,” says Sirch, who also serves as an agronomist for Terlato Family Vineyards in Friuli, Italy. “The method we developed avoids wounding the plant with large pruning cuts. Fungi and diseases can enter through the wounds, and some parasites cause the depletion of the lymphatic vessels inside the plants, first weakening them and subsequently leading to their death.”

Their method, says Sirch, enables the plants to protect themselves against disease, while also creating greater vascular efficiency and preserving nutrients so that individual vines and entire vineyards are more able to withstand extreme weather events.

In the Vineyard: Predicting the Weather

Talking about the weather with a viticulturalist can feel as stressful as discussing war with a general. No surprise, as something like hail storms can devastate an entire region and destroy an entire harvest.

So it’s no surprise that growers are deploying every tool at their disposal to — if not control the weather — manage how it impacts their grapes.

“We practice sustainable, precision agriculture,” says Antonio Michael Zaccheo, winemaker at Chianti, Italy’s Carpineto. “We have a weather station with radio-controlled transmitters throughout our 300-acre vineyard. We have thermometers disguised as fake leaves placed in the canopy to measure the temperature above and below it, and sense the humidity and wind speed.”

By rigorously monitoring micro-weather patterns, Zaccheo says that they have been able to cut back considerably on spraying regimens, while also increasing the quality of the fruit.

“If we know mildew pressure is coming, we can spray for it,” Zaccheo notes. “But that means maybe one or two sprays a season, instead of preventative spraying, which wastes resources and fuel.”

In the Cellar: Optical Sorting

When grapes come into the cellar, they’re not all perfect. Hot, dry vintages deliver raisins, cold vintages may deliver more underripe fruit. The human eye can see a lot, but an optical laser sorter “reads” each grape, measuring size, shape, color and organic structure, comparing it against the winemaker’s baseline requirements.

Over and underripe grapes, stems, leaves and other ephemera get ousted.

“We started using an optical sorter in 2017, and it has definitely affected what I think of as our house terroir,” says Halter Ranch’s winemaker, Kevin Sass. “If you have some of our older vintages, there may be signs of raisins or stems here and there. But now, even in tough years like 2020 and 2022, when we had extreme heat waves in Paso Robles and seven days of 100-degree-plus weather, we still managed to make great wines.”

They had to lose about 20% of their harvest, but Sass says the results were worth it.

“The human hand can help terroir,” Sass says. “Those vintages tasted like great vintages because we were able to get rid of the grapes that would have otherwise led to a less balanced wine.”

In the Cellar: Phenolic Assessment

Phenolics shape the way bitterness and astringency are perceived in a wine. Phenolics also determine the color of red wine. Assessing a wine’s phenolics hasn’t always been standard practice though.

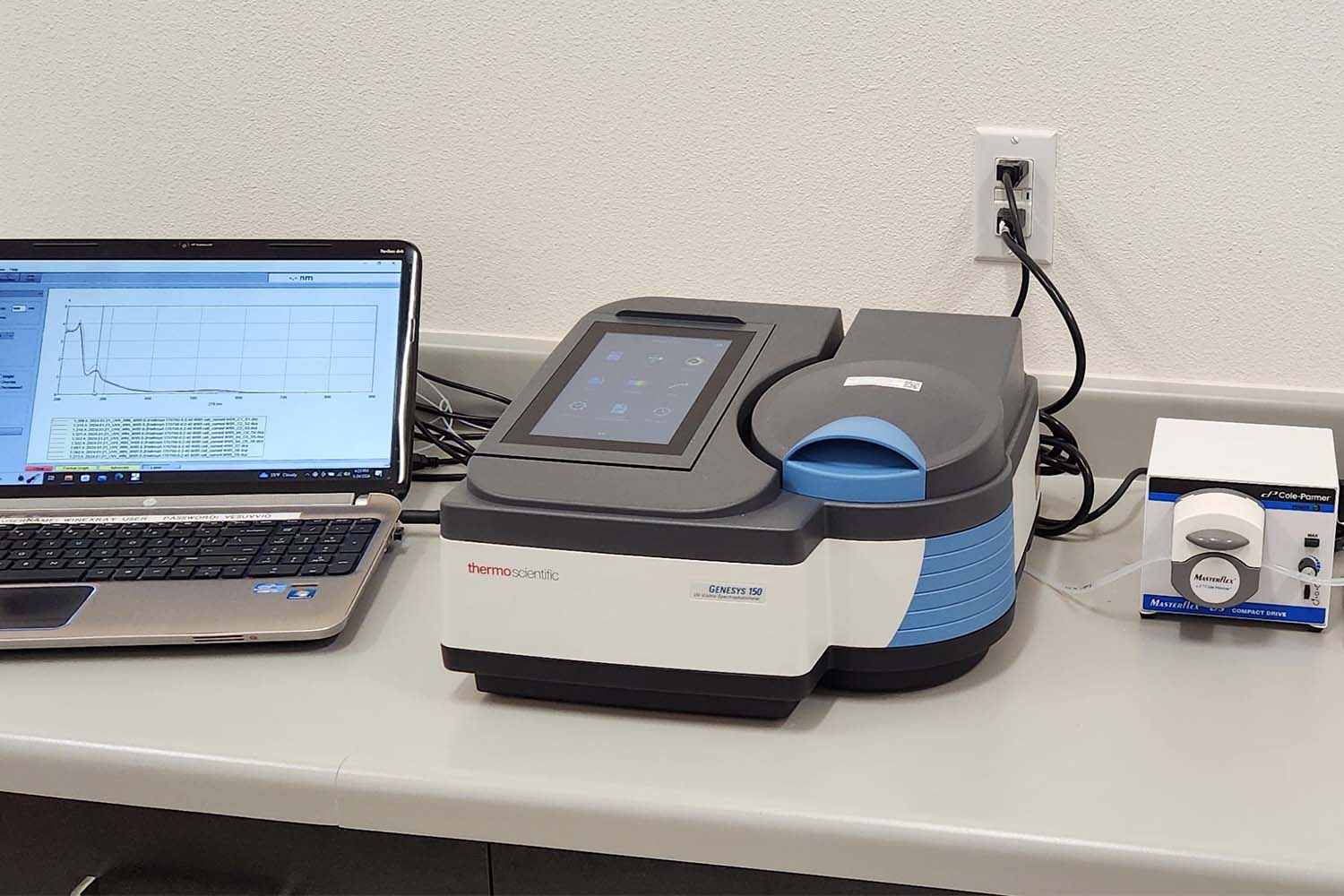

“Until recently, it was time and cost-intensive,” says Adam Casto, head winemaker at Ehlers Estate in Napa. “But recently, a new approach developed by WineXRay utilizes spectrophotometry to allow in-house analysis without the complications or cost of wet chemistry.”

WineXRay measures several variables, including color, polymeric pigments, tannins and total phenolics. Together, these compounds provide the color, texture, astringency and structure of a wine.

“By having insight into markers associated with color and tannin accumulation, it opens the door to new approaches to climate change adaption,” Casto notes. “The value of knowing where the fruit is in its phenolic maturation cycle before, during and after extreme weather events affords the grower data that better informs critical decision-making during these times. The eventual inclusion of AI and machine learning to analyze these growing data sets will continue to improve our predictive capacity, which at this time doesn’t really exist.”

In the Cellar: Computer Monitored and Aided Fermentations

When a wine is in the fermentation process, it’s a very delicate time. Tanks are monitored once or twice a day to make sure the fermentation is proceeding at the expected clip, and that sugar depletion is steady.

“But imagine if you could measure every hour, and you didn’t have to be there to do it?” Alejandro Zimman, winemaker at Stone Edge Farm Estate Vineyards & Winery in Glen Ellen, California, asks rhetorically. “We partnered with Winely, which tracks and monitors each tank remotely every 15 minutes. It measures sugar, temperature and pH, and it allows us to anticipate a problem before it really becomes one.”

Zimman says that monitoring the fermentation process so aggressively produces better wine.

“We like doing a short, fast and hot fermentation because it helps extract color and tannins,” Zimman explains. “It creates balanced and ageable wines. But it’s risky because the yeast can get too hot and excited, which can result in a sluggish fermentation. That will quickly lead to bacterial visitors, off aromas and unbalanced wines. With this tool, the process is a lot less risky.”

Enrico Viglierchio, general manager at Castello Banfi in Tuscany, says the team uses computers to control some aspects of fermentation.

“Seventy of our red wine fermenters are monitored to set temperature and pump-overs,” says Viglierchio. “This is a great help in managing so many fermentations. We also monitor by lab analysis, tasting and visual inspection. Right now we’re testing white wine fermenters that will monitor the production of H2S and CO2.”

In the Cellar: Robot Riddling

The act of riddling involves rotating a wine bottle in micro-increments to gently loosen the sediment that collects in the bottleneck, while also gradually tilting it. The process was created by Madame Clicquot in the early 1800s and didn’t change much for a few centuries.

At Rack & Riddle Custom Wine Services, which has become the No. 1 custom sparkling producer in the U.S., co-founder Bruce Lundquist says that robotic technology has not only allowed them to grow their business aggressively but also maintain a caring and ethical work environment.

“Riddling has long been done by hand, and it’s physically demanding and repetitive,” Lundquist says. “Our riddling machine holds four riddling cages on arms — think of a square with each junction as a cage. As the machine riddles the cages, the cages each turn, as does the riddler itself.”

Each metal cage holds 576 bottles or 48 cases. So per “quad” each riddler is processing 192 cases per riddling cycle. By giving robots, instead of humans, the heavy lifting, Lundquist says they’ve increased production by 100%.

It may be more romantic to think Mother Nature’s sun, soil and rain alone turned grapes from the field into poetry in your glass. But in reality, without human ingenuity smoothing out nature’s rougher edges, those beautiful sips of terroir would be left to ferment on the vine.

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.