“There’s a lot of money floating around, and stocks are not as secure as they once were. Commercial property isn’t so good in many parts of the world. Excepting Old Masters, even art is unpredictable. Crypto doesn’t look so smart now,” says Steven Smith. “If you want to know where those in the know are investing their money these days, it’s in violins.”

If that notion has thrown you, Smith can explain. He’s the managing director of J & A Beares, the violin dealer founded in London 130 years ago this year. Beares has recently completed an exhaustive study of Stradivari instrument sales from the early 1800s to the 1970s — even acquiring historic dealers W.E. Hill & Sons in order to access their records to do so. The result is the first index of Stradivari prices, one backed by KPMG at that. The result? The provable data shows that prices just keep climbing. And climbing.

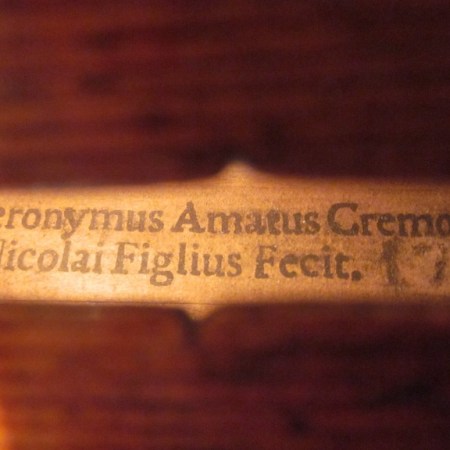

You’ll likely have heard of Antonio Stradivari — 17th/18th century violin maker, considered the all-time great, the genius pioneer of violin design and the go-to choice of superstar concert violinists every time. Many of his violins have been lost over the centuries, and many of the 650 or so known to still exist have gone into museums.

The same goes for lesser, if still historically important makers the likes of Guarneri del Gesu — Paganini’s choice — or Giovanni Guadagnini. Look too to the likes of Andrea Amati, Francesco Ruggieri or Giuseppe Guarneri. And not just to their violins, but also violas and cellos, making the market for what’s known as “fine stringed instruments.”

Two important points here: these makers are all dead, and these stringed instruments — unlike, say pianos — are among the few classical instruments that get better with age. As anyone who took Economics 101 knows, anything of finite supply but in constant demand almost always rises in value. That’s why such instruments sell for anywhere between $3 million and $25 million. Florian Leonard, London-based violin maker and dealer — and the official expert in stringed instruments for the city’s prestigious Royal College of Music — reckons the market has typically offered a 26% ROI over a 20-year period, but a 60% ROI isn’t unusual.

Such pieces are typically sold privately and very discreetly. But international auction houses are increasingly interested in selling the big-name makers at public auction. This June, for example, a Stradivarius fetched $15.3 million in New York, just shy of the $15.9 million record set for the auction of a “Strad” in London in 2011.

“People tend to buy these instruments without the need to borrow and only tend to sell them last among their assets, and that gives the market a stability many other assets lack,” explains Smith, who will be publishing a market-defining, six-volume catalogue of known Stradivari pieces next June. “The long-term returns are very, very good. And this is an asset class markets the likes of China and the Middle East — which don’t have a long culture of [violin/cello-based] classical music — are only really now starting to catch on to.”

Why a Third-Generation Toyota 4Runner Is the Best Gear Investment I’ve Ever Made

Why my SUV from the ‘90s is the automotive equivalent of Leatherman or Darn ToughBut there is, he stresses, more to fine stringed instruments than the chance for speculation. Sure, as an asset class they’re also easy to store and easy to move around the world. And insurance costs aren’t overbearing because fencing such well-known instruments on the black market would be next to impossible. More appealingly, owning such an instrument is also an entree into the rarefied world of classical music — because invariably owners are encouraged to lend their instrument out to a player whose talent would benefit from it.

“This is not a big market — relative to art, say — because there are so few instruments in circulation, which is why so few people tend to know about their investment potential. That and because not so many people have connections within the classic music world, or an interest in it, as they might to the art world. After all, there are major art galleries in many cities,” explains Robert Dumitrescu, director of the St.Gallen, Switzerland-based Guarneri Society, which holds a collection of some of the world’s best violins and helps people invest in them.

“But your money does go further — what you pay for an historically important violin won’t buy you much in terms of historically important art,” he adds. In the spring, the society will also launch the first program offering the opportunity to invest in shares in certain instruments, widening the market out to those considerably less well-heeled. “And, what also appeals even more to investors now, is that it’s a chance to be a sponsor of the arts. It’s a philanthropic point of distinction. You know, there are people who buy art, and what’s their motivation? They hang it on their wall, their friends come round and say ‘Wow, you’ve got one of those.’ Well, who cares? To own a violin like these is something very different.”

As Dumitrescu notes, these instruments are only getting more and more expensive, such that even the world’s best players can’t afford them themselves, limiting their art in the process. Owners can make that access happen, with themselves becoming some small part of the history of their instrument. That’s a win-win too: not only is the canon of Western classic music largely made up of works requiring stringed instruments, keeping up demand, but having your violin played by a famous virtuoso — a Julia Fischer, a Joshua Bell or a Sarah Chang — only tends to add to your instrument’s value.

“I’m pleased to say that most buyers who come to me have the education to appreciate why these violins shouldn’t be hidden away in vaults, which is reassuring,” says violin broker Roman Goronok. “Most of my job is in finding these instruments, in keeping track of them, and in, as someone once said of the art world, knowing which painting is on whose wall. I have my little black book, so I know where these violins are, who’s using them, which players may be near the end of their careers and so looking to release their instrument back into circulation, which players are coming up and need one. These are just extraordinary objects. They deserve to be played.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.