There’s something special about sipping a whisky that’s older than you are. There’s no guarantee that it will be objectively better than younger whiskies on the shelf, but trying a whisky that was resting in a barrel since before you were born feels celebratory and indulgent. This is an attainable treat in your twenties, when such a dram is a spendy but not outlandish splurge. The price accelerates as you get older. By your thirties and forties, you might be looking at a week or more of rent for the experience of drinking one of these super-aged whiskies.

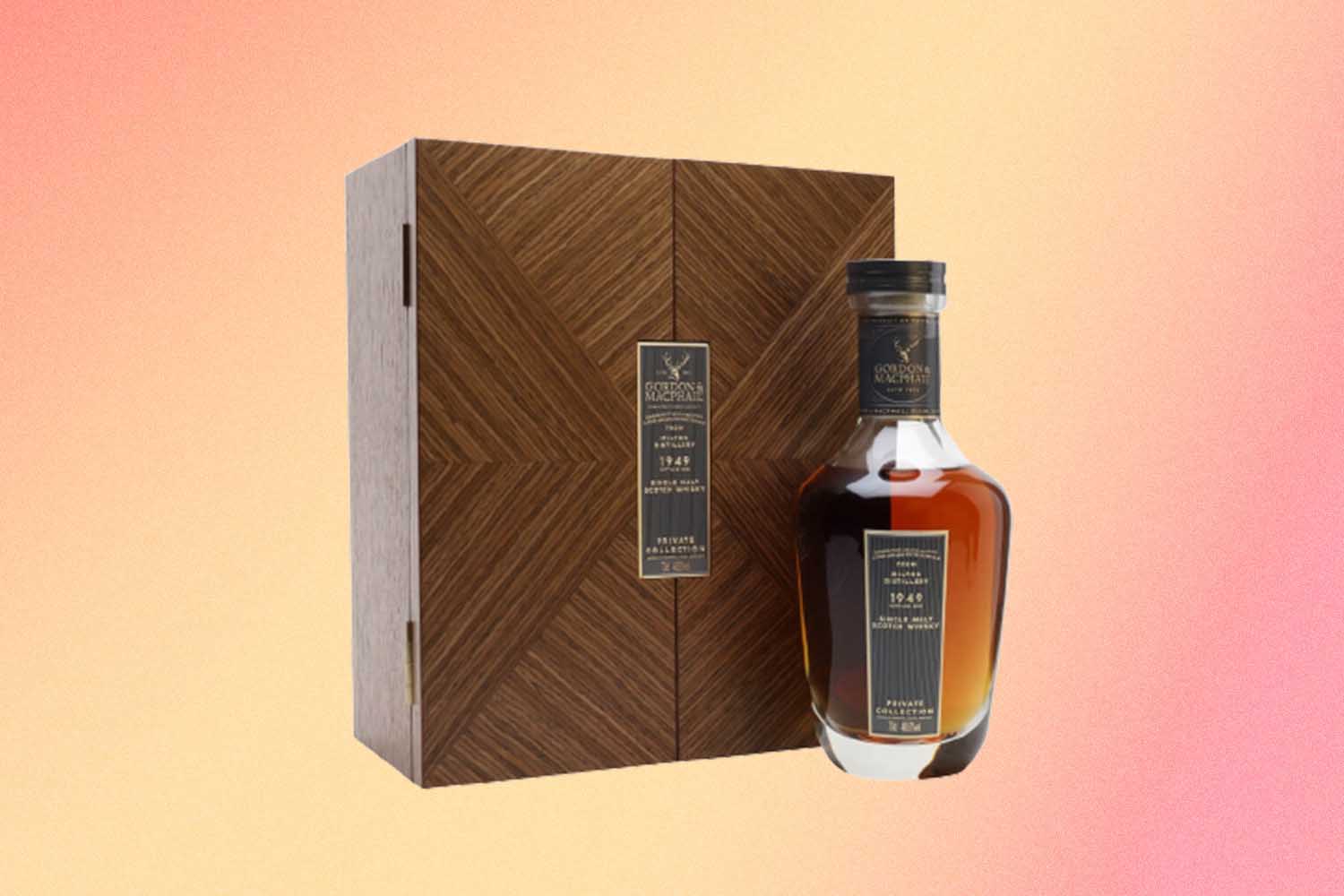

Therefore, I was very excited when, on the eve of my fortieth birthday, I received an unexpected sample of whisky that was not only older than me but older than my dad: a 72-year-old Scotch bottled by Gordon & MacPhail. Distilled in 1949 at the Milton Distillery, now known as Strathisla, the whisky spent seven full decades in a first-fill sherry puncheon. Nearly three-quarters of a century after filling, the cask yielded just 180 bottles at a strength of 48.6% ABV, each of them retailing for about $65,000. That meant my little glass vial represented about $2,600 worth of Scotch. It would quite possibly be the oldest and most expensive whisky I ever drink in my life. I took care not to drop it.

Obviously, I was eager to taste this remarkably aged spirit, but I was also intrigued by the business of making a whisky this old. Seventy-two years is an absurdly long time to wait for a return on investment. The person filling that barrel in 1949 couldn’t have expected that the spirit would remain there until well into the twenty-first century. Throughout all those years the cask was losing volume too, the dreaded “angels’ share” sucking valuable whisky into the air through evaporation. Having known plenty of craft distillers walking the tightrope between aging their spirits long enough to reach maturation and generating sales enough to keep the lights on, the idea of hanging on to a cask of Scotch for seventy-two years struck me as an inherently wild prospect.

“You have to respect what they’re doing,” Robin Robinson, spirits brand consultant and author of The Complete Whiskey Course, told me. “Gordon & MacPhail really do consider themselves the stewards of ancient Scottish whisky history. I’ve been through their warehouse and I’ve seen some phenomenal barrels.”

“Extreme-Aged” Whiskies Are a Big Deal, But How Old Is Too Old?

How distillers and blenders keep “extreme-aged” spirits on track after 50 yearsGordon & MacPhail is an independent bottler, meaning that the company specializes in aging and curating whisky from a variety of Scottish distilleries. Independent bottlers can offer very good Scotch, but they don’t necessarily enjoy the international brand recognition of an acclaimed single malt distillery or a big name in blending such as Dewars or Johnnie Walker. Releasing an exceptionally aged whisky is one way they can bring attention and prestige to their company.

There’s clearly a marketing benefit to releasing an incredibly old whisky, but this would be nothing more than a cynical ploy if it weren’t actually good. This is a genuine risk, since older isn’t necessarily better. Robinson notes that he’s tasted plenty of whiskies that were aged too long, becoming flabby and fat. The oak can become excessive and the spirit’s vibrancy lost.

Sipping Super-Aged Whiskies

This won’t always be obvious when one first tastes a whisky. “We’re humans, we live to be tricked,” says Robinson. Knowing that a whisky is old and expensive elevates one’s expectations; the experience of tasting it when knowing its provenance may be very different than when tasting it blind. Robinson was optimistic, however, that Gordon & MacPhail’s selection would be worthwhile, noting the company’s unique ability to care for their casks.

“We’re in a privileged position where we have a library of stock,” says Stuart Urquhart, operations director at Gordon & MacPhail, noting that this stock consists of about 35,000 casks. They are systematic about sampling and picking casks to set aside for extended aging. These tend to be American oak sherry casks, which he says impart flavor and color to the spirit more slowly than European oak or ex-bourbon barrels. Gordon & MacPhail also store their casks intended for extended aging at the very bottom of racked warehouses, keeping them as cool as possible.

The casks the company sets aside today are similar to the ones they have held onto for decades for a special release. Urquhart’s great-grandfather would have been filling casks at the time the Milton went into the barrel, not anticipating how long it would end up resting there. “They weren’t filled for that purpose,” says Urquhart. “They just naturally developed into casks that could be kept for a long period of time.”

How does one determine when such an old whisky is finally ready to bottle? “Once they get very old, after thirty years, we’ll sample them at least once a year. Over fifty it can be every six months, over seventy can be every month,” says Urquhart. When the quality is finally where they want it, they make the decision to bottle it. “One of the hardest lessons I’ve had to learn is you can’t keep things forever,” he says.

Personally, I find it hard to imagine what it’s like to taste a seventy-year-old whisky and say, “No, it’s not quite there yet, it may need another couple more years.” But that’s part of the enviable job for the tasting panel at Gordon & MacPhail.

So, 72 years after going into a sherry cask, how does this Milton whisky taste? Sampling it with a friend, we picked up notes of old leather and cedar chest with a hint of fruitiness on the aroma. On the palate, hints of peach and cantaloupe lead into a dry, woody finish with a bit of hazelnut or almond. Though still lively for its age, its long time in oak came across on the finish.

We greatly enjoyed it. Yet for its price and rarity, there’s a temptation to expect more, to think one might be granted access to new vistas of taste unlike any you have ever experienced. That’s not how it works. In the end, although it is excellent, even a carefully aged seventy-two-year-old whisky is still within the realm of very good Scotch. This makes it difficult to write about or review such spirits. If you ask me whether a whisky is worth its $40 or $100 or $300 price, I have some sense of how to give an answer. When we wade into the range of whiskies that have aged for many decades and sell for tens of thousands of dollars, this pragmatic perspective breaks down. We exit the range of normal consumer reviews grounded in how a product tastes and enter the realm of rare, subjective experiences.

In the case of this Gordon & MacPhail bottling of a 1949 Milton, that means tasting a whisky laid down in a cask just a few years after World War Two. It’s a unique opportunity to engage sensuously with the historic past. I can’t possibly tell you how to price that. (Though if you’re so inclined and have an extra $65,000 in your pocket, there is at least one bottle still available for sale. You may also want to check out GiveWell.) I do know that I am glad that such bottles exist in the world, and I appreciate that their rarity is driven by the true challenge of selectively aging them for so long rather than by trend-chasing or viral media hype. I’m happier still that I got to taste one.

Gordon & MacPhail is in it for the long haul, so expect more extensively aged scotches in the future. In fact, they’ve just released two of them: the third edition of their Mr. George Legacy series, a 1959 Scotch from the Glen Grant Distillery aged for sixty-three years, and a Glen Grant from 1948 bottled to commemorate the coronation of King Charles III.

There are only 281 bottles of the latter, and it’s aged two years longer than the Milton bottle. I could tell you that I love its richness, nuttiness and hints of smoke and citrus zest, and that would all be true. It’s a privilege to taste it. But this is also a reminder that reading about whisky is no substitute for actually experiencing it. As Urquhart says, “You can’t keep things forever.” This applies to casks as well as to individual bottles. So if you do end up with one of these rarities, I hope you’ll resist the temptation to merely collect it. Open that bottle and share it with a friend. Even after seven decades, whisky is for drinking.

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.