Here’s an age-old vignette that probably feels familiar to everyone scattered across the universe of sports fandom: a parent consoling a sobbing child as whatever nemesis franchise celebrates on television. The family team has been eliminated from the playoffs. The world knocked off its axis.

We’ll get ’em next year, the parent says. Inside, they’re actually thinking: I feel those tears, kiddo. I wish someone would hug me right now, too. This is all my fault. I did this to you, didn’t I? I just couldn’t help myself.

Like it’s a curse or something. Only that’s dead wrong. It’s a blessing. Every loss, every late-season collapse, every ill-timed injury, every retirement by a team captain, every pilgrimage to the arena that cost an arm and both legs — it’s all a gift, a lifelong bundle like no other. Even the unluckiest fans, the ones whose parents’ parents never saw a playoff win, are luckier than those who don’t root for any team at all.

Don’t believe me? Then believe Ben Valenta and David Sikorjak, the authors of Fans Have More Friends, the guys who actually did the research. Valenta (the SVP of strategy and analytics for Fox Sports, and an erstwhile consultant with clients like Nike, the NFL and ESPN) and Sikorjak (the founder of Dexterity Consulting, and a former executive at Publicis, NBC and MSG) had a hunch that in the end, fandom was a good thing. Maybe even a social good.

So they got to work, compiling first-person interviews with broad-scale analyses in order to stitch together an idea of what fandom does to us. Far from dooming our progeny to decades of misery, they discovered that fandom appears to be a priceless inheritance — a built-in form of a belonging, and a bright-burning lighthouse in an increasingly lonely world.

The Untold Story Behind Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney’s Welsh Football Club

48 hours of songs, pints and unexpected friendships. This is one adventure you won’t see on the FX series “Welcome to Wrexham.”We recently had the chance to pepper the pair with a variety of questions about sports fandom’s relationship with friendship, happiness and mental health. Including: Does it matter what sports you follow? Are younger generations as interested in fandom as old heads? And how does fandom relate to that male friendship crisis we keep hearing about? Find our full interview below, which was conducted through email and includes a combined response from Valenta and Sikorjak, and find their book (which is well worth the read!) here.

InsideHook: What initially inspired you two to explore the relationship between sports fandom and social wellness?

When we first set out to understand the fan experience, we didn’t expect to become advocates for fandom’s ability to address widespread social problems like loneliness and polarization. More than anything, we were dissatisfied with the prevailing discourse around fandom. We knew that fandom offered us something more profound than conventional wisdom prescribed…but we could not articulate precisely what that was.

Our goal was simply to piece together a more authentic picture of the fan experience. We learned along the way that social connection is the driving force motivating all fan behavior. To be a fan is to be a part of a community. For any fan, that statement feels intuitively true. The social nature of fandom feels so familiar and relatable that it’s often rendered nearly invisible. People take it for granted, accepting it without considering its implications. This only made us more curious.

Intrigued, we started to connect the dots between fandom and social wellness. If fandom is about community, then it should improve the social lives of sports fans. If fandom helps to improve the social lives of sports fans, then fans should reap the positive benefits of socializing. In retrospect, the logic of it all is so clear. And once we saw it, we could not unsee it. The social benefits of fandom sprang up everywhere.

According to your findings, how does one’s sports fandom correlate with their overall sense of well-being and happiness?

As the title of our book states, fans do have more friends. Moreover, they value those relationships more and engage with those people more often. The same is true for family relationships, too. In other words, sports fans are likelier to have a close relationship with their mothers, fathers and siblings than non-fans. And yes, engagement amplifies this effect: not only do fans have more friends than non-fans, but more engaged fans have more friends than less engaged fans.

When it comes to well-being, it’s all this additional socializing that impacts measures of happiness, optimism and satisfaction. We are social creatures by nature, and social connection is a critical component of a happy, fulfilled life. Fandom is only relevant here in that it reliably brings people together; it’s the coming together that impacts a person’s well-being. If you peel back the layers, what we’re ultimately advocating for is more belonging. That’s the end; sports are simply the means.

Do you think men are actually going through a “loneliness crisis” at the moment? How can fandom help, if so?

The loneliness crisis is very real. The U.S. surgeon general recently released a report entitled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation.” While the data in that report demonstrates that this pernicious problem affects all demographics, the issue does seem to be particularly acute among men.

The thing about loneliness is that it is effectively the absence of meaningful social connections. The antidote, then, is to inspire and facilitate more social connection. In other words, the solution to loneliness is belonging. This is where fandom comes in.

If you understand the power of fandom, you can use sports proactively for specifically social ends. Sports remove social friction by giving you a reason to interact.

For example, it can feel weird to send a “How you doing?” text to a friend randomly on a Tuesday night, but it doesn’t seem strange to send a “Did you see that game?” text. It feels completely natural and organic. So, if you need an injection of social activity in your life, invite a couple of friends over to watch a game. If you’re feeling disconnected from your peers at work, start a fantasy league. If you’re missing your family, start a group text about your hometown team.

These examples can help us think about solutions on the individual level, but it’s worth extrapolating this to the societal level. The reason fandom has so much potential to affect positive change at a population level is that it is already something that tens of millions of people are participating in. Fandom isn’t a solution that requires people to adopt an entirely new behavior; it simply requires people to lean into something they already enjoy doing. Our mission is to make people — especially fans — conscious of this power so that they can leverage it with purpose.

In your research, did you find differences in the social benefits of fandom for individual sports (like tennis or golf) versus team sports (like soccer or basketball)?

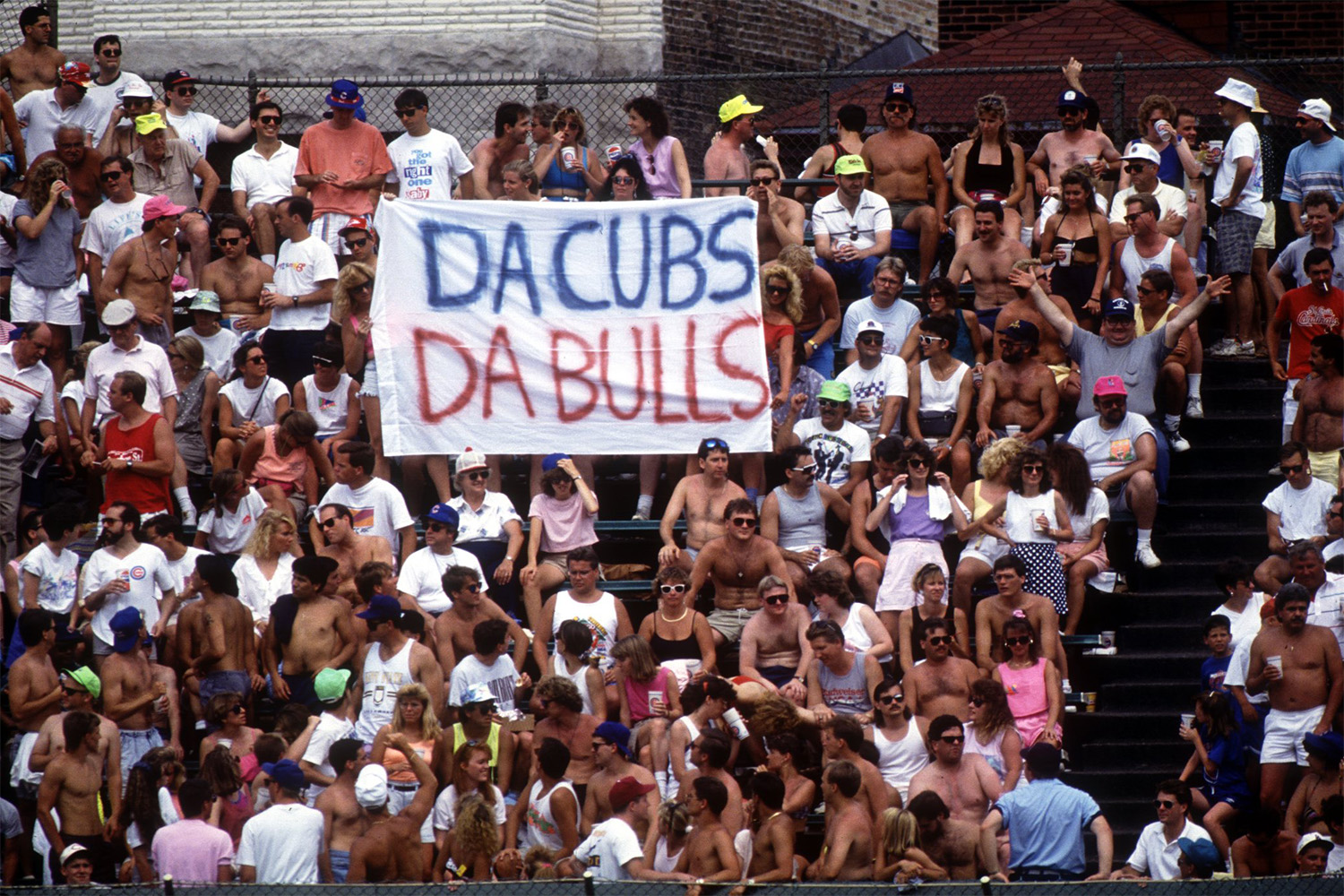

The main focus of our research is on team sports, so we didn’t do deep dives into individual sports like tennis or golf. That said, we identified an indisputable logic at work that helps answer your question. Generally speaking, we do not see significant differences between sports. But the social benefits increase as a person adds more sports to their portfolio. In other words, if you isolate populations who are only NFL fans and those who are fans of the NFL, NBA, college basketball, and, say, golf, the multi-sport fan is likely to have more friends, be happier, and be more trusting and engaged in society. Effectively, fandom has a compounding effect: each sport activates different social circles, takes place at different times during the calendar and has unique rituals associated with it. So, the operative question is “How many sports?” rather than “What sport?” If one is following other sports in addition to being an avid fan of tennis, they will experience more benefits than those who just follow tennis, and so on.

I once read something to the effect of “NFL fans are fans of the league, MLB fans are fans of their team and NBA fans are fans of a player.” Do you have any thoughts on these various flavors of fandom?

We’ve heard this formulation before. There is some truth to it, but we would hesitate to draw any significant implications from this framing, which mostly comes down to structural differences between the sports. Different structures lead to different behaviors.

NFL teams play once a week across a relatively short season (17 games per team), and, while there are games played on Thursdays and Mondays, the majority of games occur at the same time on Sundays. This makes the NFL, as a league, relatively easy to digest. Fans have an easier time watching teams outside of their local market, and it also makes things like fantasy league participation that much easier.

By contrast, MLB and NBA teams play a longer season (162 and 82 games, respectively), with games played every day of the week, which makes it much harder to follow at a league level. There are simply too many games to keep track of, so fans focus more on their local team. This explains why one would say that NFL fans are fans of the league, but really, the more precise way of saying it is: NFL fans are more likely to watch a more significant share of games across the league. But the reality is the primary way a fan relates to each of those sports is through their local team. We continually measure team fandom for each sport, and most fans — regardless of the sport — are fans of their local team first.

On the court, the NBA provides a unique experience. There are only 10 players on the court in a confined space with no protective gear, and one player can have a tremendous impact on the game. With baseball, you will only see a star player get four or five at-bats in a game. Football players are part of a large roster, have their faces covered by helmets and only play half the game. But with the NBA, the stars are involved in almost every play throughout the entire game. Plus, a star player has far more impact on the game, both offensively and defensively. This leaves the fan with a far greater exposure and appreciation for the NBA player as compared to watching players in the other sports. So, when some say “NBA fans are fans of the player,” it’s because NBA fans have far greater exposure to the star players. Still, what’s interesting is that these differences don’t change the fact that the majority of fans are connected to their local team first.

Your work mentions the positive impact of fandom on family relationships. Can you share insights or examples of how sports can strengthen family bonds?

Engaged fans do tend to have stronger familial relationships. The bigger the fan, the more likely they value their relationships with their mother, father and siblings. More engaged fans are also more likely to express satisfaction with their family relationships and home lives, too.

What’s most interesting to us is that fandom’s impact is felt in both directions. We’ve recently surveyed teens and found that the bigger the fan, the closer they will report being to their mother and father. Going the other direction, we have also surveyed parents, and we found that the bigger the fan, the stronger their reported relationship strength was with their children.

There is no mystery as to what’s going on. Sports provide opportunities for family members to engage with each other. And that opportunity to engage is around something fun and relatable. Going to a game together is quality family time. Watching a game at home together is quality family time. Texting each other during a game is familial interaction that would otherwise not take place. Families can do other things to stay connected, but sports provide an easy on-ramp because sports are fun. We’ve recently done qualitative research with teens, and we often heard something like, “My parents are fun when watching sports.”

How Text-Only Relationships Can Help Solve the Male Friendship Crisis

Inside the curious rise of “digital confidants” — friends who go years without meeting in the same placeIs it still “cool” to be a fan? Are Gen Z and Generation Alpha poised to carry the fandom torch? Or will there be too much competition for their interests as they continue to grow up?

This is something we are currently exploring. There’s a lot of handwringing in the industry these days about the next generation of fans, and for good reason. As you point out, there’s a lot of competition for attention these days. We’re bullish. We believe in fandom, primarily because fandom is a way to fulfill the basic human need to engage with people (and the world) in a positive way.

The trick to winning over the next generation — and every generation thereafter — is to reframe how we think about fandom. Our current cultural conception of fandom often frames sports as entertainment. A fan buys a ticket to see an entertaining spectacle, so surely that spectacle must be “cool” to remain relevant. But the thing is, it’s not about the spectacle. This might be counterintuitive, but the reason fans engage is not the players on the field, but the people in the stands. Sports are undeniably entertaining, but that’s not the primary job they do for fans. When a fan buys a ticket to see a game, what they’re buying is belonging. That’s something more powerful than TikTok trends and Taylor Swift and any notion of “cool” entertainment.

This doesn’t mean that we’re not concerned about the next generation of fans. Fandom grows organically with each generation, but we would argue that we (as fans) should be more deliberate about cultivating the next generation of fans. As parents, we recognize the importance of passing down fandom to our kids because it is a positive social force. Framing fandom as a social facilitator has become our mission today.

How do some of fandom’s less savory behaviors (booze, betting, trolling, hooliganism, etc.) impact that sense of well-being you’ve written about?

This is an important question, but the way we frame it matters. The way the question is worded presupposes that things like alcohol abuse and violence are caused by sports. We would argue that these problems are not caused by sports, it’s just the venue where we often see their impact. In other words, the guy who gets in a fight in a stadium bathroom line after having too many beers is the same guy who would get in a fight in a barroom after having too many beers. Sports are just the context where these things can unfold. Now, we are not turning a blind eye to these behaviors. Yes, they happen, but they’re the exception, not the rule. And they get all the attention: two drunks get into an altercation in the stadium parking lot makes the local news; but the father and daughter sharing five hours of quality time at the same stadium doesn’t get the same coverage.

At the end of the day, we’re arguing that we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bath water. Let’s not let a few bad actors obscure the positive impact sports have on society. In fact, one of the core motivations for writing this book was to disabuse people of these less savory associations with fandom. The bigger the fan, the more likely one is to give to charity, spend time with family, attend religious services, read for leisure, host a family dinner, participate politically and have greater confidence in our institutions. That is the impact of sports fandom. Sports fandom is an overwhelmingly positive force.

Lastly, we devote a chapter to betting. While acknowledging it is not for everyone, the one fact about betting is it pulls you deeper into fandom. Most bettors end up being highly engaged fans, what we call High-Value fans in the book. And it is the High-Value fan who has more friends and is happier, and so on. In the book, we compare High-Value fans who are bettors and High-Value fans who do not bet to see which group experiences more benefits. When you compare across metrics, the bettors show up on par or ahead of the non-bettor. This is all a function of betting pulling them deeper into fandom and thus experiencing more of the social benefits that come with elevated fandom.

What do you make of the growing trend of “sportwashing,” in which dubious companies, states or investment funds pour money into teams or leagues? Is it possible (let alone ethical) for fans to ignore these money sources?

It’s important to recognize the scale of sports. The British sportswriter David Goldblatt has an interesting essay called “Football Is Everything,” in which he describes soccer’s cultural impact around the world. The fact of the matter is that sports operate at such a scale that to think they would be immune from bad actors strikes us as naive. To borrow Goldblatt’s language, if sports are everything, then they are bound to intersect with vast sums of money and unsavory characters who have ulterior motives. I wish it wasn’t the case, and maybe this sounds like a cop out, but sometimes the world is complicated. And this is nothing new. The term “sportswashing” is new, but the phenomenon that term describes was not invented by some nasty oligarch last week. Unsavory characters have been involved with sports — because of their culture-wide appeal — since there was such a thing.

We’re also left wondering: what’s a fan to do? The framing of the question assumes there is something the individual fan can do to prevent bad actors from spoiling sports. Imagine a team has been part of your family’s intergenerational fabric for over a hundred years, and then some unscrupulous character buys it from some other slightly less unscrupulous character. You could stop supporting the team, but would that really do anything? And why should you give up this birthright? And where do you draw the line? Nation-states with a history of human rights abuses might seem obvious, but are we sure we know where the latest billionaire’s fortune came from? Was it all above board? Again, it’s complicated. Each fan is going to have to make that decision for themselves: where do you draw the line?

This isn’t to turn a blind eye to bad actors, but it does put in sharp relief how important these institutions are. Sports and fandom are worth protecting. If sports go away, the money and prestige that incentivizes bad actors go away, but so does the social foundation of millions of people while the bad actors remain unfettered. If sports facilitate social connections that make people better off, then removing those sports will decrease social connections and make people worse off. Sports are a social good.

Are there changes that need to be made — either by players, or the press, or owners — to further foster fandom, or cultivate it in a more responsible way?

This is a big question, and we are researching the answers as we speak. For the sake of brevity we like to think about it like this:

For the fan: Lean into what you already enjoy doing; it is a good thing. When you watch a game with someone, you are not just watching a game or rooting for a team; you are deepening relationships. And that, win or lose, is good for you. Too often, we frame fandom negatively as some sort of vice or mindless behavior. Whether one knows it or not, it is a good thing.

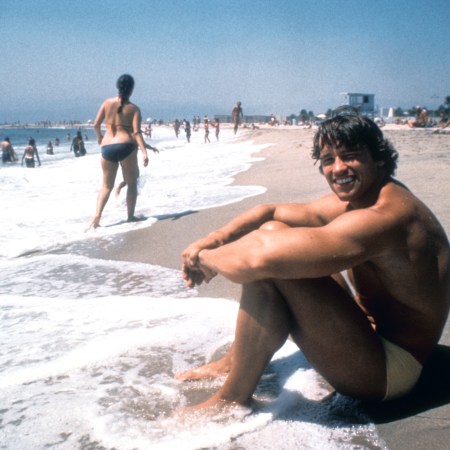

For parents: Start them young; if you do, you will increase the quality time with your children and create memories that will last a lifetime. Moreover, you will give your kids social currency they can utilize as they navigate this world. If you want to increase the chances of your kids having robust, active social lives, give them the gift of fandom. It’s like a social superpower.

For the sports business: Recognize that your product is belonging, not entertainment.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.