After water, the second most used substance on the planet is concrete. It’s true. Concrete is the backbone of international infrastructure — buildings, highways, sidewalks, bridges, dams, sports arenas, they’re all made from concrete.

On a broad scale, that isn’t going to change anytime soon. By 2050, the production of cement, the main ingredient in concrete, is expected to increase by two billion tons a year, which is … unfortunate. While cement is cheap, widely available and extremely strong, it also puts a massive strain on the environment. Cement makes up 5% of the carbon emissions pie; heating one ton of cement in a kiln happens to release one ton of CO2 into the atmosphere. As one chart from The Guardian pointed out two years ago, if concrete were a country it would be the third-largest carbon emitter in the entire world.

Which is why some towns are increasingly looking to move away from the material, and move back to one most communities left in the 19th century: wood. There are a growing number of “plyscrapers,” or multi-story buildings built from cross-laminated timber. Check out the list of the tallest wooden buildings in the world — the majority were built in the last decade, and there are proposals for dozens more (in places like Tokyo, Portland and Helsinki) over the next 15 years, with some boasting 70 or more floors.

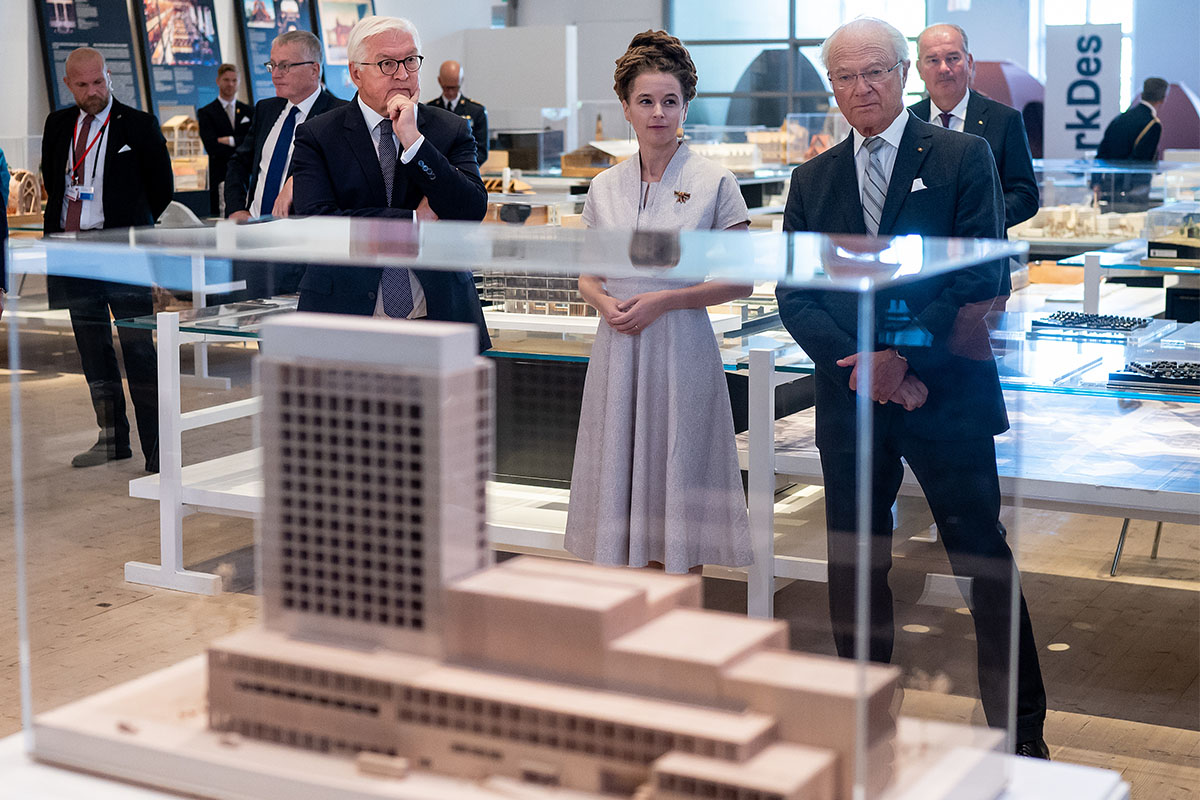

One place pioneering this trend is Skellefteå, a city of roughly 75,000 people in northeastern Sweden, which recently opened Sara Kulturhus, a culture center with a theater, museum, art gallery, public library and hotel, as reported by The Guardian. The 20-story building is made largely from treated wood (a combination of glued laminated timber and cross-laminated timber), which “is lightweight but as strong as concrete and steel.”

That wood comes from local forests — where developers make sure to plant additional trees for each one they cut down — and doesn’t just save the environment from whatever carbon a concrete project would’ve emitted. The building can actually store carbon, to the tune of 9,000 tons. Not to mention, building with wood is a quicker, easier process. Truck deliveries to the site were slashed by an estimated 90%, and a year of labor was saved as workers were able to put together the assembly-ready panels at a pace of one story every two days.

We’ve long accepted construction sites to be noisy, dusty, polluted places where quality of life is low. But that doesn’t have to be the case when you’re building with wood. As one contractor told The Guardian, “The people building this would never go back to steel and concrete.” And for those concerned about how the wood reacts to fire or moisture, don’t worry. Today’s cross-laminated timber is prepped to protect against wood’s old foes.

To be fair, the complex isn’t built only from wood. There is a massive weight-bearing steel truss, and the top two floors include some concrete to bolster the building against the area’s subarctic winds. This is a general reality for plyscraper: barring future architectural advancements, there is a built-in cutoff on height.

But perhaps that’s a good thing. As cities start to rethink empty lots and sprawl, it might be time to trade in those unimaginative 40-story office park slabs for gathering places that actually enrich the environment — places communities will gravitate towards and be proud of. Click through photos of Sara Kulturhus here. The wood doesn’t just have a positive impact on the planet, it’s soft and gentle on the eyes, too.

As always with Scandinavian triumphs, there may be a natural inclination to roll your eyes. As in: Yes, beautiful, but it would never happen here. Skellefteå, after all, is also a 100% renewable energy city, which runs on hydropower and wind. But these are attainable goals that the U.S. can (and needs to) start pushing towards. When beautiful, wooden wonderlands await on the other side, it might be a little easier to get everyone on board.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.