Among a green landscape of Scotch pine, Douglas fir and Fraser fir, 12-year-old Larry Evans noticed mushrooms growing under one of the trees. His mother, being a biologist, saw his curiosity and decided to place a book in front of him. Before long, he not only knew the name of what he was looking at, but deemed it safe to eat. At 18, he moved away from Illinois, the site of his family Christmas tree farm, to Montana to further immerse himself in the world of microbiology, plant botany and medical mycology. While in college, he studied in the edges as there was no fixed curriculum on mushrooms.

A few winding decades later, I’m at the 42nd annual Telluride Mushroom Festival in Colorado to sit down with Larry Evans, who now claims the title Mushroom Guy of the Mountain West, an unofficial moniker that recognizes his work as a mycologist, field guide, teacher, organizer and founder of the Western Montana Mycological Association. The only problem? Larry is nowhere to be found.

I’ve been at the festival for two days. In between edible mushroom forays in search of delectable chanterelles and porcini, lectures on the phylogenetic relationship of different mushroom species, and culinary demonstrations on the versatility of cooking black trumpet mushrooms, I’ve attempted to correspond with Larry. Or at least the fabrication of Larry in digital form (an email address and his Instagram handle, @mushroomlarry). At one point, I hear back from the festival organizers that “sometimes he has a phone and sometimes not.” In the concerted effort to track down this mushroom guru, someone mocks our attempt to use a phone as a means of finding him: “Larry doesn’t even have shoes!”

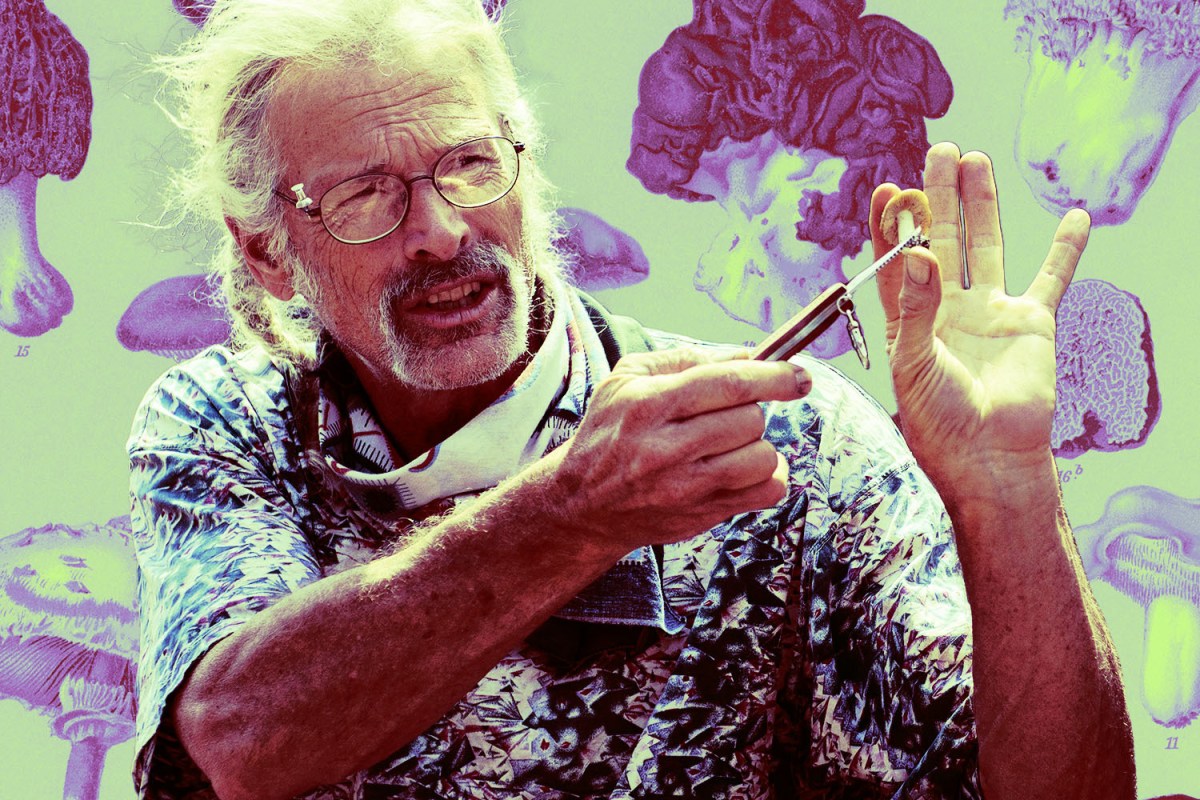

Three days in, the festival is in full bloom. It’s a crisply wetted, late Friday morning. I’m at a lecture listening in on the biocultural conservation efforts in the Amazon by renowned ethnobotanist Dr. Mark Plotkin. I notice a grizzled yet sleek figure twirling his tousled hair into Dutch braids. The playful enigma is seated two rows ahead of me in the lecture hall. He’s garbed in a washed out tie-dye long-sleeve shirt, rectangular eyeglasses and a full beard. It’s Larry Evans. He does not have shoes on.

Between lectures, I approach him where he’s sitting cross-legged in the auditorium seats. “Hi, Larry Evans?” He looks up, warmly bewildered by the mention of his name. He revels in the serendipity of us finally meeting. We exchange pleasantries. A tiny caucus forms to soak in his knowledge of the benefits of various species of mushrooms in Latin America.

After a presentation from Dr. Laura Guzmán-Dávalos, an international Psilocybe expert and mycologist, Larry, his partner Wendy Smith and I make our way to a coffee shop in the middle of Telluride. The walk turns Homeric. True to his prestige, Larry and his phone are separated. He regards it as “a temporary inconvenience.” I can’t tell if he’s referring to the phone or the situation.

The Sundown Town Road Trip: A Black Adventurer’s Journey of Discovery

This spring, Joe Kanzangu set out to explore the diversification of the great outdoors in places that were previously built to excludeWe take a damp midday stroll from the east end of the mountain town onto bustling Colorado Avenue. Residential houses run into small trinket shops and eateries.The sun, partly covered, highlights the well-manicured aspen trees and bright green yards. Larry is routinely approached like a sage stimulant. Some people simply wave at him, some say hi with such enthusiasm he can’t help but stop; he inspires others to walk around the still-wet sidewalks barefoot. He’s even invited onto a lawn to investigate the growth of reishi (Ganoderma) mushrooms on a tree.

“The joy of being Larry is that everyone feels connected to him,” remarks Wendy. A few oyster mushroom viewings and some party invites later, we arrive at High Alpine Coffee. The journey truly was the destination. Between bites of premade breakfast burritos, chocolate pastries and a few sips of tea we dive into the corporate-influenced, systemic impact on vulnerable environments. “I’m not an optimist,” Larry declares, “nor am I a pessimist. I’m an activist!” He doesn’t believe it’s too late to address our current climate crisis. He believes it’s time we all stop daydreaming and act in service of our planet by implementing new models of operating.

In 1977 and 1979, Larry took classes with Orson Miller, a polypore expert and author of Mushrooms of North America, at Yellow Bay Biological Center in Montana. This experience equipped him with professional knowledge on fungi and an elevated understanding of mushrooms. After teaching classes in mycology at the University of Montana from 1980 to 1982, he moved to Japan for two years and then lived in Korea for another two. In Japan, he made a living as a judo practitioner and English teacher.

He made his way home to the States in the late ‘80s. Back in Montana, he was importing and exporting materials such as silver out of Mexico, selling furniture from Korea and working as a private contractor. Between trips he also spent time as a tree planter. During the winter he would go down to Mexico to be a beach bum. In 1990, he went back to the University of Montana to teach ecology, mycology and biology as an adjunct professor — not that he had previously paused his fungi hobby.

“I was moving mushrooms at the same time,” he says. “When you find a mushroom, sometimes you find a lot! That’s just how mushrooms are.” Suddenly, right off the back patio of the coffee shop where we’re sitting, Larry breaks into a melody. His tone, saccharine, turns heads at a few tables around us as it amplifies.

“So I’m a mushroom guru, I get questions all the time. Somebody’s got a woody conk or a pile of yellow slime, but it ain’t about science man, it’s more about me. Cause the only thing they ever wanna know is: ‘Can ya eat it? Can ya eat it? Can ya eat it?’”

After the chorus, Larry explains his unexpected performance. “I wrote that [song] out of frustration because I would be identifying mushrooms over and over and I’d be interrupted every single time by somebody asking, ‘Can ya eat it?’” he says. “There’s so much more to mushrooms than our need to consume them. They’re important to many ecosystems. They help with water retention and fire control. Mushrooms are so versatile, you can grow them, turn them into filters, packaging, and they even eat up toxic waste.”

“You cultivate mushrooms for so many reasons,” Wendy, Larry’s source of motivation, says during our lunch. “We’re growing oyster mushrooms for ecological cleaning projects. [As a society,] we can include Indigenous and Native tribes that already know how to do this; we can all learn how to better help our earth.”

Since the ‘90s, Larry’s devotion to mushrooms has taken him to Canada, Bolivia, Ecuador and back to Missoula, Montana, where he now resides. The abundance of species in the Mountain West propels him to lead mushroom forays throughout the region, including at the annual Telluride Mushroom Festival. “We can grow water filtration systems that take out heavy metals with mushrooms,” he says, adamant that mushrooms are the future and the future is in waste. “We can filter large amounts of mining wastes through mushroom filters — we can take rivers, literally, and run them through, and [this] takes out the heavy metals that are killing animals and destroying whole ecosystems.”

There are bio-cultural conservation efforts large and small happening all around us, if we take the time to look. In speaking with Larry, I gained a better understanding of the importance of building new systems to combat our current climate issues. As we say our goodbyes at the coffee shop, it feels less like a farewell and more like a “I’ll see you when I see you.”

The Telluride Mushroom Festival, for all its eccentric quirks, feels like an apparatus for action. And Larry Evans, for all his eccentric quirks, is all about that action. The rest of my day I’m further reminded of the restorative practices already set in place. There are so many ways to connect with our planet, from mushroom forays in your backyard to being a steward for land conservation in a forest near you, and the more we’re cognizant of our impact, the better we can act.

As it happens, I bump into Larry later that night at the festival’s closing drum circle and celebration. He offers me some mushroom tea. I take my shoes off and exhale.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.