Workwear can be a touchy subject in the menswear community. While anyone can read up on Neapolitan tailoring or American Ivy style, an intimate understanding of workwear requires getting your hands dirty — something that information-economy drones might never experience, no matter how many pairs of Redwing boots and Carhartt overalls they amass.

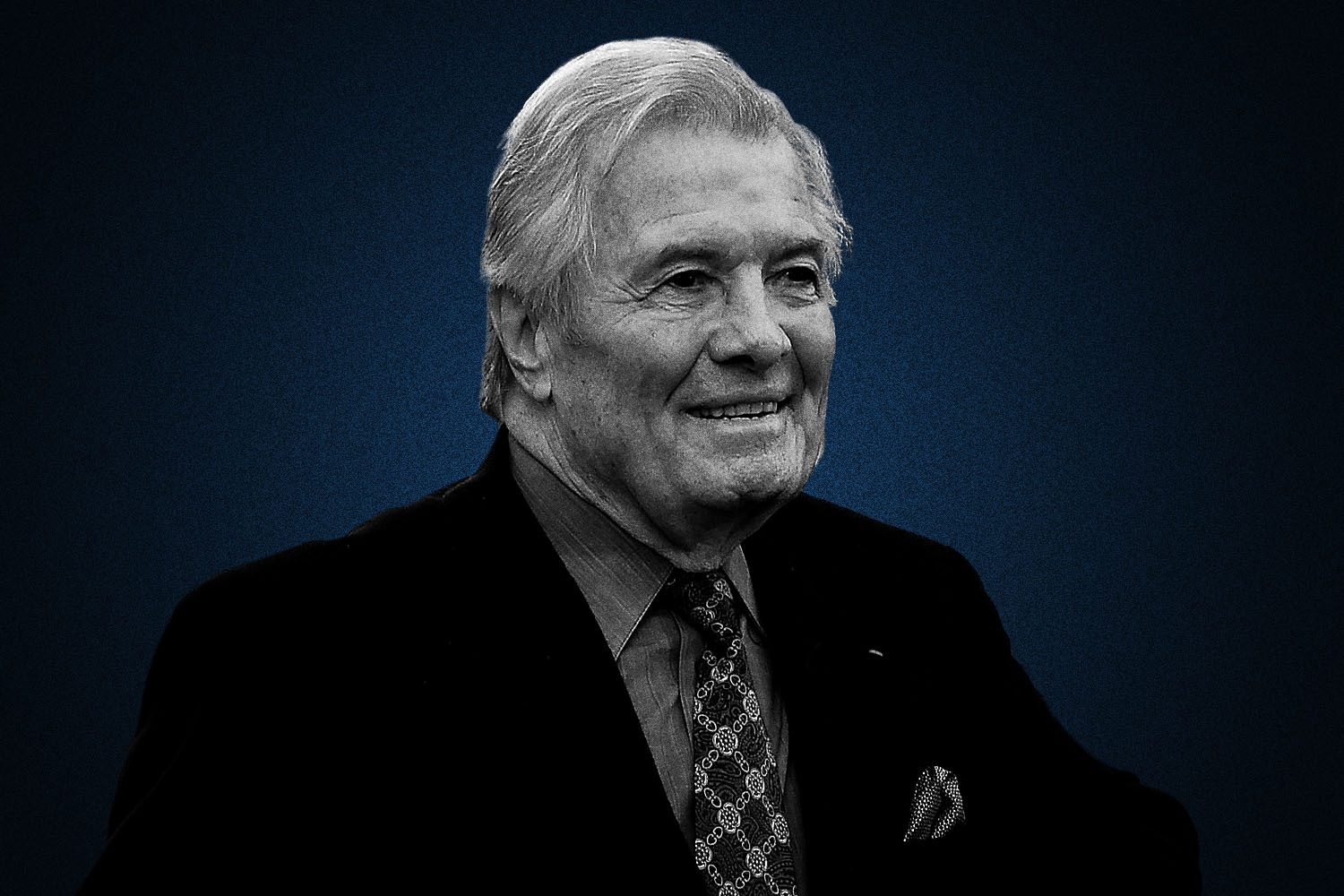

But to borrow from meme parlance, Peter Zottolo is truly a man who can do both. Under his nom de Instagram @urbancomposition and role as the US Director of Plaza Uomo magazine, he documents bespoke tailoring from San Francisco to Sicily. But in his day job, Zottolo works as an inside wireman with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local Union 6 (rough translation: electrician).

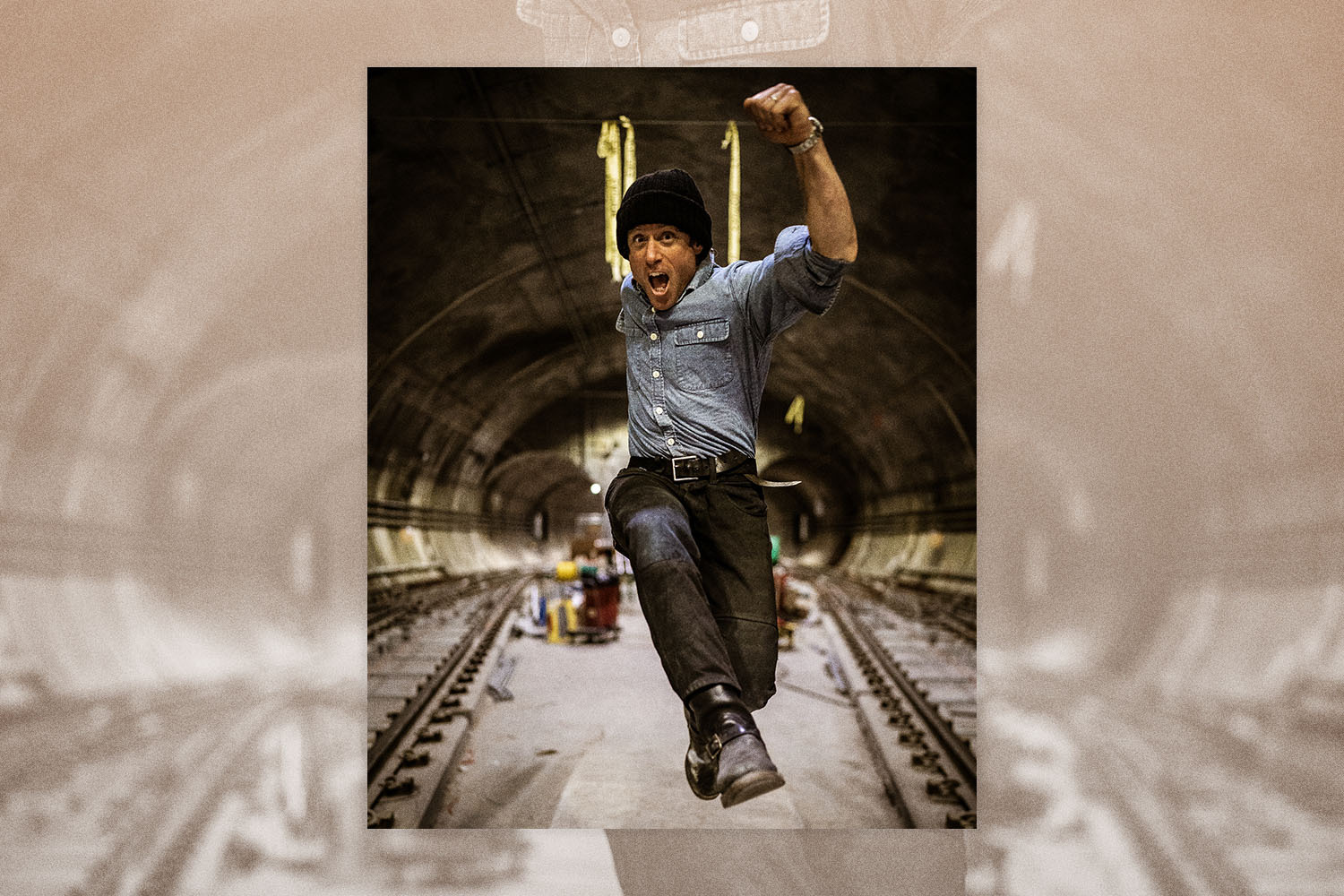

Which is to say, Zottolo is a guy who knows fit and fabric inside out but has also spent weeks working below the rails of San Francisco’s subway system. So we went to him to figure out what brands stand up to the test, how one builds a workwear wardrobe, and who gets to wear it in the first place.

Know What You’re Paying For

To begin with, there’s a divide between the most accessible and inexpensive of workwear brands — think a $30 pair of Dickie’s — and the labels that sell $300 jeans through boutiques and websites like Self Edge.

He also explains that higher prices don’t necessarily mean that a garment will last longer, but should be coupled with other important considerations. “What you’re paying for is not necessarily longevity. You’re paying for craftsmanship, you’re paying for people making a living wage, you’re paying for design,” he says.

Another point in favor of upmarket sellers is that they’re more willing to repair or replace an item that loses a button or unravels early, a service that the cheaper end of the spectrum won’t offer, but that Zottolo has experienced firsthand through Self Edge.

Below the Work Belt

For lower-body wear, Zottolo endorses the basic, $50 double-front duck canvas Carhartt pant with space for kneepads. While the basketweave of duck canvas means they’ll rip faster than diagonally woven denim twill, they’re ubiquitous on work sites thanks to their low price and wide availability. He adds that he also owns two pairs of Carhartt overalls that are reserved for the dirtiest jobs.

However, Zottolo is happy to pay a premium for jeans that retail north of $300, like those made by the Stevenson Overall Co. He appreciates their 220 Carmel jeans for their higher rise and fuller thigh, which makes them more suitable for work, as well as a tapered calf that allows them to be worn with sport coats and loafers once job-related wear-and-tear retires them from work duty (that’s right: Zottolo pairs jeans with tailoring only after they’re too beat for work).

But no pant gets quite as much praise as the “Unbreakable” motorcycle jeans made by Australian motorcycle/workwear brand Saint. Retailing for about $400 or more, the jeans are woven with Dyneema, a fiber that’s 15 times stronger than steel and commonly used to make bulletproof vests. In motorcycle parlance, this gives the jeans a slide time of seven seconds — a valid concern for Zottolo, who rides a motorcycle to and from work — but also hardens them for the most physically demanding jobs.

In particular, Zottolo cites wearing their Unbreakable Model Four with inserted kneepads while working on San Francisco’s upcoming Chinatown subway station. For a month, Zottolo had to work on his hands and knees in a three-foot-high space below the train tracks. At the end of the job, the jeans had only suffered a bit of fading, while most of his co-worker’s pants quit halfway through.

Above the Work Belt

Zottolo names Taylor Stitch’s Yosemite shirt as his most frequently worn work shirt, thanks to the softness and durability of its cotton flannel chamois fabric. But he’s also partial to the American-made work shirts sold by Gustin, which come with the added benefit of having open rather than flapped chest pockets.

“If you’re working, you don’t have time to open up a flap pocket,” he says.

These Boots Were Made for Workin’

On the subject of boots, Zottolo highlights two makers that were overlooked during the mid-aughts craze for all things “heritage.” He appreciates Thorogood for making many of its boots in the U.S.A. with union labor. “For less than 200 bucks, you get a really good pair of well-made, Goodyear-welted boots,” he says.

But he’s also happily paid more than twice that for the engineer-style Boss boot made by Wesco, a family-owned company located in Scappoose, Oregon. Zottolo attributes the boot’s higher price tag to the thickness of the Wesco’s house leather, which has made it his longest-serving work boot.

“To give you an idea, the leather lining that they use for the shaft of the boot is thicker than most work boots,” he says. “That’s just the lining. If you add the outside leather, it’s not indestructible, but it’s really close.”

Count to Three

Deciphering signs of durability can be difficult for desk jockeys, but Zottolo offers an easy, visual identifier for sussing out quality workwear: triple needle stitching. This mark, which can appear on the cheapest or most expensive work shirts and jackets, simply means that the garment’s side-seams have been secured with three rows of stitching rather than one.

“If one row of stitching fails, you have another two to back you up,” he says.

Starting from Scratch

So you’re ready to roll up your sleeves and dress for a real, work-related task? “You can’t go wrong with a $50 pair of [double-knee] Carhartts,” Zottolo says. “You won’t be out of pocket that much and they will last a decent amount of time. It’s a good place to start.”

For work shirts, he “wholeheartedly recommends” Gustin, contending that they provide “The most bang for your buck as far as longevity and design.”

Overalls for Everyone

One of the thornier questions when it comes to wearing workwear is authenticity, which has led to not wholly ironic accusations of “stolen valor” whenever a latte-sipping Brooklynite dons steel-toe boots and overalls on their way to a social media job. Zottolo, however, doesn’t buy it.

“There’s a lot of people who say you shouldn’t wear workwear unless you are actually in a job that requires it. I personally don’t like that kind of gatekeeping.”

He cites the changing nature of office dress codes, mentioning that 50 years ago it would have been inconceivable to wear jeans, a workwear staple, into a cubicle. Today’s it’s de rigueur.

“If someone wants to wear workwear to the office, I personally don’t think there is anything wrong with that, and I don’t like that kind of mentality. If you want to wear that kind of stuff and your environment allows you to, go for it.”

In other words, wear whatever works.

This article was featured in the InsideHook SF newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Bay Area.