Studying propaganda can be a fascinating way to see how wars are fought without using anything traditionally considered “weapons.” The Second World War abounded with plenty of intriguing examples of this — and if you’re not familiar with the story of Surrealist artist Claude Cahun, brace yourself for one of the most unexpected tales of art being used to fight fascism ever recorded. Cahun’s battle against the Nazis wasn’t the only place in which complex theory was used to defeat the Nazis.

In his new book How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler, Peter Pomerantsev chronicled World War II’s propaganda front through the life of Allied propagandist Sefton Delmer. In an excerpt published at CrimeReads, Pomerantsev focuses on the efforts of Delmer’s colleague John T. MacCurdy, the man behind a series of pamphlets that urged German soldiers to fake illnesses and leave their fighting days behind.

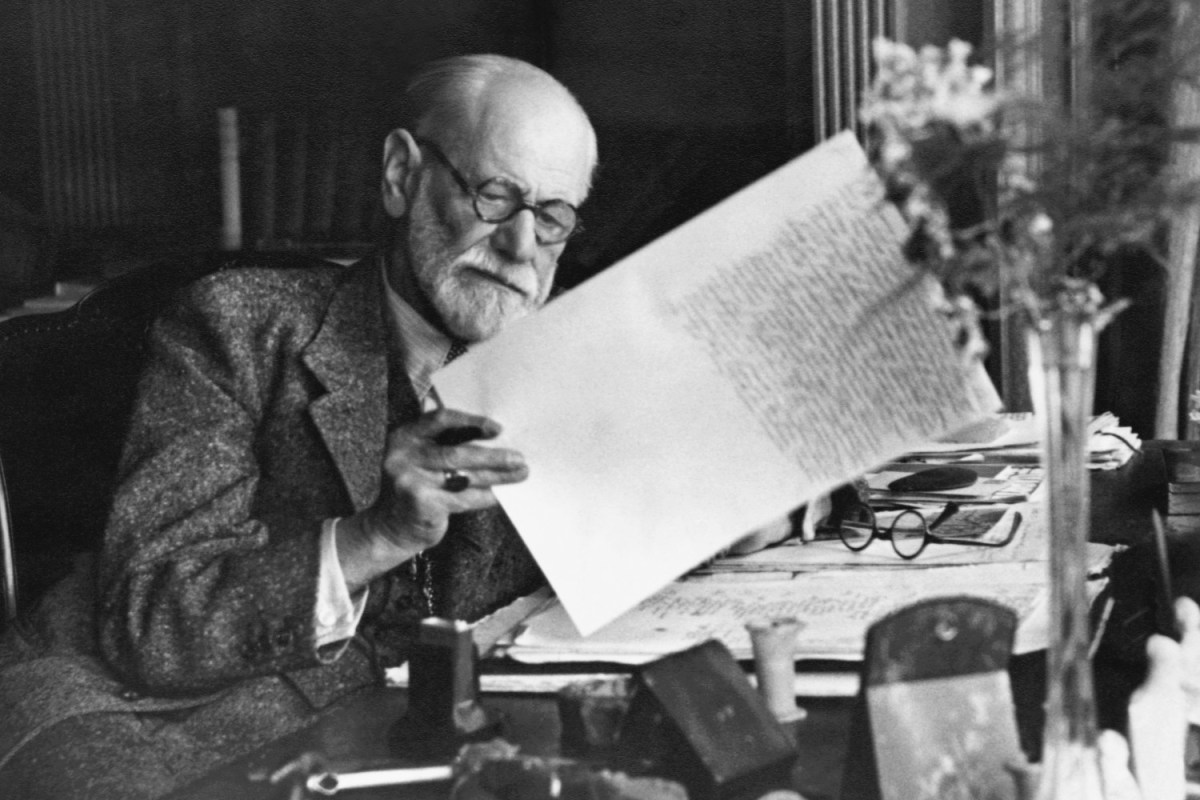

What led MacCurdy to this concept? His work, as Pomerantsev puts it, “working out what could make death attractive in the first place.” And that led him back to a certain Viennese thinker who transformed our notions of how the mind works — specifically, Pomerantsev writes, to the concept of the death drive, or thanatos.

Did the FBI Once Consider “It’s a Wonderful Life” Communist Propaganda?

Turns out that oft-reported story is a little more complicated, but unfortunately true enoughAs writer and psychoanalyst Josh Cohen told Pomerantsev, MacCurdy saw a way to use Freud’s theories to undermine the German military. “Freud believed it bumped up against a desire to live and was then turned outward into aggression: we kill others so as not to kill ourselves,” Cohen said. Using propaganda to suggest a different path — one which also relied on Freud’s theories — offered a fascinating alternative.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.